Bocsu JUNG, Savina Museum of Contemporary Art

Birth

1955, Uiryeong

Genre

Painting, Installation

Homepage

Bocsu JUNG's Figure Painting: The Masked Human Image

Traditional figure painting has not been mainstream art for quite some time. Today, it is considered an inferior genre. One genre of figure painting, portraiture, was once the very most important genre of all since most of the subjects were the rich and powerful. Needless to say, the heyday of portraiture has long since passed. In Western society, it gave way under the increasing influence of humanism to painting of idealized human images, and these were done for quite a long time. Out of respect for the human character and while emphasizing the noble aspects of man, Western painters depicted women resembling Venus and men resembling Zeus or Mars, the Roman god of war. This figure painting, too, like the portraiture before it, was very important but would eventually fade in the face of a new genre of painting. Entering the 20th century, figure painting was supplanted by landscape, still life, and abstract paintings.

In Korea, figure painting had never been as important a genre as paintings of the Four Noble Plants or landscapes, which had been done for centuries. Human figures were depicted as trivial beings hiding behind a rock or in a valley seeking the essence of nature in all its unspoiled grandeur. Even so, there was some hint of humanism as the literati, gentlemen of the Joseon dynasty, were seen as aspiring to realize an ideal life. Be that as it may, contemporary figure painters, be they Western or Eastern, took little interest in the figure painting of by-gone times, even though it seemed to be truly genuine. Figure painting began to depict 'man’s true nature' instead of outward appearance.

Human Nature Instead of Outward Appearance

Although traditional figure painting does not enjoy such great favor as it once did, it has survived to this day. Portraits of iconic 20th century figures like Marilyn Monroe, Mao Tse Dung, and Elizabeth Taylor by Andy Warhol still exert great influence, and portraits by Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud are some of the most highly prized art works around the world. Many self-portraits in contemporary oil painting, photography, video art, and other media are shown to the public today. Nonetheless, today’s diverse figure painting is unique in so many ways.

Although traditional figure painting does not enjoy such great favor as it once did, it has survived to this day. Portraits of iconic 20th century figures like Marilyn Monroe, Mao Tse Dung, and Elizabeth Taylor by Andy Warhol still exert great influence, and portraits by Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud are some of the most highly prized art works around the world. Many self-portraits in contemporary oil painting, photography, video art, and other media are shown to the public today. Nonetheless, today’s diverse figure painting is unique in so many ways.

Modern figure painting can be understood as having focused on the outward appearance of the subject, while today's figure painting strongly tends to address the essence of a man that is sensed in the deep experience of living. It mainly explores human nature itself in the context of today’s highly competitive society characterized by survival of the fittest. Whereas sociobiologists analyze the physiology and ecology of animals and insects, contemporary figure painters analyze the psychology of men by their exquisite brush strokes. They sometimes serve as a high-definition camera exploring the physical body of men, and other times, they are like exquisite antennae detecting the senses of the human body cringing or shivering in fright before something and analytically recording their findings into what could be considered a diagram. They create a scientific mystery of the human body with form and color, and ceaselessly sneak a look and sense and imagine the domain of the mind and soul. They even imitate the anger and joy of others in their portraits.

It is true that man remains the orthodox subject of Western fine art, which personified nearly everything. The subjects of life and death, sex, power, and politics are all subtitles of 'man'. Portraitists have tried to depict individuality, personality, character, social status, achievement, and even philosophy of the subject in portraits. Even abstract painting, which seemingly has nothing to do with figure painting, aspires to express a sensible bond of sympathy with the inner spiritual world of man. In many respects, fine art is a pioneer of anthropology.

It is true that man remains the orthodox subject of Western fine art, which personified nearly everything. The subjects of life and death, sex, power, and politics are all subtitles of 'man'. Portraitists have tried to depict individuality, personality, character, social status, achievement, and even philosophy of the subject in portraits. Even abstract painting, which seemingly has nothing to do with figure painting, aspires to express a sensible bond of sympathy with the inner spiritual world of man. In many respects, fine art is a pioneer of anthropology.

The Masked Human Image

Many years ago, Jung Bocsu said that his figure painting was a record of the 'agony of man and the vanity of the body' and a 'psychological map of eternally lonely man'. Jung's figure painting seems to show uncertain contemplations running through philosophical human images and biological human images materialized as images. Some aspects of his figure painting are representations of the perceptions of his ego, the conscious "I", and other aspects inspired by what others have done. As a result, he contemplates the chaos that occurs where "I" and others are undistinguishable, and the agony and vanity of others are identified with his own (agony and vanity). It is for this reason that nearly all of the figures in Jung's paintings are naked. Nakedness itself tends to express the essence and purity of man and upholds the universal human image into which both oneself and others are united. Jung's figure painting is still a record on memories of the body, and formatively expresses contemplations based on the biological existence of the body.

Many years ago, Jung Bocsu said that his figure painting was a record of the 'agony of man and the vanity of the body' and a 'psychological map of eternally lonely man'. Jung's figure painting seems to show uncertain contemplations running through philosophical human images and biological human images materialized as images. Some aspects of his figure painting are representations of the perceptions of his ego, the conscious "I", and other aspects inspired by what others have done. As a result, he contemplates the chaos that occurs where "I" and others are undistinguishable, and the agony and vanity of others are identified with his own (agony and vanity). It is for this reason that nearly all of the figures in Jung's paintings are naked. Nakedness itself tends to express the essence and purity of man and upholds the universal human image into which both oneself and others are united. Jung's figure painting is still a record on memories of the body, and formatively expresses contemplations based on the biological existence of the body.

In this regard, Jung shares something in common with existentialist figurative painter Francis Bacon. In Bacon's painting, the human is shown to be merely a chunk of meat with sensory function and a nervous system. Bacon's painting shows survival only through the body decaying as meat, sexual pleasure by sensory function and the nervous system, and mouths screaming in response to such pleasure. There is, therefore, no mask of any kind in Bacon's figure painting. Even the skin, which is akin to a mask for the body, is removed. Bacon focused on the animal character of man, which has only a nervous system.

Jung never does this in his figure painting. Rather, Jung is the opposite of Bacon. Jung's figure painting sheds light on human nature that is perhaps a product of a mask. In fact, to hide one's face from others is ultimately to hide it from oneself, and a mask is perceived as a very unethical thing. But, what is behind the mask is still man. Because the face hidden behind a mask is real, it is quite humane. Surely, Jung will continue to do figure paintings until he finds our real faces. Until our true whole and parts are all seen transparently……..

Ik-yeong YUN (Art Critic)

more

A Memorandum of Existence: The Primary Relationship Between Destiny and Desire

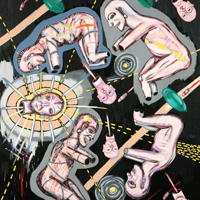

Since 1979, starting with a private exhibition, Jung Bocsu has been working on the subject of the “body,” drawing the face and the internal organs on the naked human form. He renders the internal organs on a stripped naked body with a bald head, drawing a simple face?the eyes, nose, lips, and ears in a three-dimensional manner, as if making a collage. The background of the canvas?as if connecting outer space and the human being?is left empty, while the individual and the society that surrounds him are represented by the human body, with words occasionally inserted here and there. Therefore, his drawings bring to mind anatomical charts that reveal unseen parts of the body, or of illustrations of meridian points commonly used in Eastern medicine. In order to expose the greed and excreting nature of humanity, Jung Boc Su refers to the stripped naked body, and like a tool kit takes apart, or amputates?so to speak?the area of the face, the insides and outsides of the body and reassembles them, creating human stories. Language is crucial in his work and by using metaphors in his titles, he is able to specify his subject matter, which assists in the viewer understanding his artistic motives and expressions. His symbolic and metaphoric way of creating art is communicated as an overall sensation through text and language.

In this private exhibition, his oil paintings, sculptures, and installation pieces from 2006 to 2011 are displayed, and unlike his previous works, in which drawings were dominant, these pieces are characterized by diverse mediums and bright, intense colors. Artificial flowers, dolls, masks, these objets d’art function as matieres on a canvas of paint, and the uninhibited touch and use of bright colors are an attempt to communicate the human forms pertaining to the times.

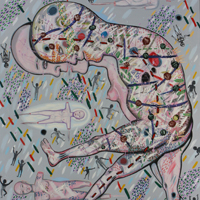

The Internal Organ’s Memories (2010) links his previous works by illustrating the relationship communication with the outside starting with the internal organs. A naked middle-aged man stands in the middle of the canvas, his bulging stomach as center, his face slanting upwards, displaying his winding entrails. A snake-like tube with the eyes of strangers burrows its way from the outside into the chest (heart) of a man, affecting his internal organs, while fragments of speech become colorful dots pouring forth from the ends of the tongue, which is connected to the thickest part of the digestive tract. This colorful stream violently shakes the canvas, affecting and providing pleasure to the organs inside the artificial body, drawn in rubbed-out fashion with an achromatic pencil. The sound comes through the ear, passes through the thin and deep intestine, then exits through the anus. The eyes of the human form, after seeing fragments of the vibrant colors (desire) of the outer side, makes the brain aware, creating provisional desires here and there while supporting its core, the back. In this way, desire, circulating as production and consumption, penetrates the man. In Words Spoken in this World (2008) the man, in the typical form of a phallus, is centered on the canvas and positioned perpendicularly, crying out in self-conceit.

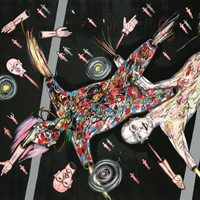

The man with red skin spots wears respectable beige underwear with flower prints, furtively exhibiting several small, erect penises. The dark shadows cast around him suggest that the man lives a cheap life, one in which he could never properly express his desires. While the kinds of men Jung Boc Su depicts have stiffened faces and large torsos, they have weak genitals and are portrayed as mere big mouths yelling only about their lives, acting haughty and stubborn. On the other hand, the woman with a child in her womb is presented as a liberated individual by outlining her contours on the plywood and corrugated cardboard. She is portrayed as a peaceful presence who can freely move about in any space. The figures in Travel through Space (2008-11) are drawn diagonally, appearing as if they are traveling in high velocity, maximizing the sense of freedom. Space Atmosphere (2009-11) is about the drama of birth: from maternity, that is like a constellation in the sky, to a baby being born and embarking into the real world. Paintings and three-dimensional works are installed together, ultimately illustrating a human being’s life journey that begins with the stars and concludes on earth. In the series, The Structure of Existence (2003-10, and 2004-10), Jung Bocsu illustrates that humans are beings of materialistic desires, an assemblage of parts. A chopped off face, body, and legs become fragments of organs and create a kind of microcosm on canvas, and as they connect they become one vision. On an empty background, these mannequin-like beings work with each other, and inside their heads or torsos, tiny parts attach or separate themselves, assembling the whole and operating as strategic instruments that comprise this world. In particular, the face can be attributed as operating as a kind of symbol of deceit that one can switch according to whether the situation is about faith, power, or money. In Existence’s Mourning (2007-11), Anniversary (2011), The Art of Conversation I (2011), the expressions on the front, side, top, and bottom are all different on the masks, and are attached like a relief painting, extending these expressions beyond conventional limitations.

Masked people stand facing forward in the frames, imparting a sense of voyeurism, as they appear to be watching others without showing their own faces. At the same time, it is a work that wholly represents the face as a technical tool of communication that frequently changes expression in accordance with relationships and situations within society. These series also present three-dimensional works, created by drawing the interior of the human body on real mannequins. They are in stark contrast with the abstract and two-dimensional bodies, which appear rather virtuous and much like the image of God, and collide with the canvas, prompting the beholder to experience a new space and time. The ontological search of Jung, who has lived over half a century, ranges from human fundamentals?love, encounters, birth, death?to various social issues such as religion, freedom, politics and war. In Encounters (2006-11), faces are placed on top of human heads and genitalia; in Study of Relations (2006-11), one’s ear is connected to another person’s esophagus; in Nightmare-Childbirth (2005), a chest is a container and a mouth gives birth; Smiling Woman (2004-06) intensely stares, grinning ; The World Is (2005-11) depicts faces in various expressions yelling at the world; in Life (2007-08), the artist paints grey faces, which have endured harsh lives, and draws the phrase “Let us love life” like an echo. Just through facial expressions, all of these works deliver the artist’s strong message. Facial expressions are represented as a function derived from an interaction between rules and relationships within society. Like Sartre’s definition of a humanist, that is, in order to love humans one must first hate them, the faces of Jung contain sublimated lives from the bits of vomit. In Birth of Religion (2006-08), he presents the smiling face of God, whose hands?tools for indulging in materials?are cut off. The expression is that of nirvana, magnanimity and love. In contrast, the bodies sprinting towards something with every fiber of their beings are the motif of Obsession and Death.

In Freedom and Chaos (2010), body parts are even more dismantled and arranged freely in space. From the sign system of Deleuze and Guattari?where hands, the ultimate tool of technology, are contrasted with faces, the ultimate tool of language?the tools and language produced in a free competitive system emerge incessantly, creating only a chaotic state on canvas. On the other hand, in A Letter from Paradise (2008-2010), the man and woman lying naked on a bed of flowers appear peaceful. The middle-aged couple look like Adam and Eve, but have not succumbed to the temptation of the forbidden fruit, maintaining their innocence. The man has an erection yet he seems relaxed instead of desirous, and the woman is in fact sleeping in peace. This piece causes the viewer to simultaneously experience a point of view from above looking down, and a direct point of view, which allows empathy with the plastic flower petal objects attached to the canvas and the tree branches installed in front of the painting.

The spiral coexistence of the present and the primitive age in The Moment When a Flower Falls (2008-11), which was displayed with a three-dimensional work made from the head of a mannequin, present ontology within a macrocosmic world. Jung Bocsu continues to live and work in Korea, a nation that is experiencing drastic changes of modernization and ultramodernization, not only in politics and economy, but also in daily life. The personal story of relationships and communication experienced by the artist is concluding towards an epic saga of more maturity and depth. Today, events and accidents happening throughout the world are broadcast in real time and cause a bigger shock than any soap opera, taking us on an emotional rollercoaster. Living in this materialistic world of irrationality and madness, we can consider the life of the ordinary couple?existing along with nature and the time of the universe?a new paradise and a mystical model. In this exhibition, the personal memoranda of Jung Boc Su, previously conveyed as expressional paintings, freely move across mediums?paintings, sculptures and installation works?via raw materials found in the artist’s daily life, expanding the senses of the beings of destiny and desire.

Mi-jin KIM (Professor, Hongik Graduate School of Art, Review & Planning)

more