Painting of the Everyday

What is important is not replicating the world, but interpreting it.

- David Hockney-

Kim Jiwon, who has stubbornly carried on the painting genre for more than 30 years, is known as an artist who endlessly questions the subject and the image, investigating the essence of painting. His painting journey began in the late 1990s with The Beginning of Painting—In the Corner (1994-2004), composed of paintings about painting. It has moved on to series such as 34x24 (1995-2001), consisting of daily landscapes painted in identical size; Similar Wall, Same Wall (1998-2007, 2013- ), which satirized society through similar-looking walls easily found throughout the country; Daily Life (1995- ), representing landscapes of the everyday in a peculiar way; Still Life, Painting (1999-2004), presenting new still life paintings of objects magnified; Vinyl Painting (2000-2002), which revealed light and shadow by painting on transparent plastic, thus creating another space within the canvas; Mendrami (2002- ), the artist’s most famous work; Take off (2002- ), and Landscape (2002- ).

Contemplation on “Painting”

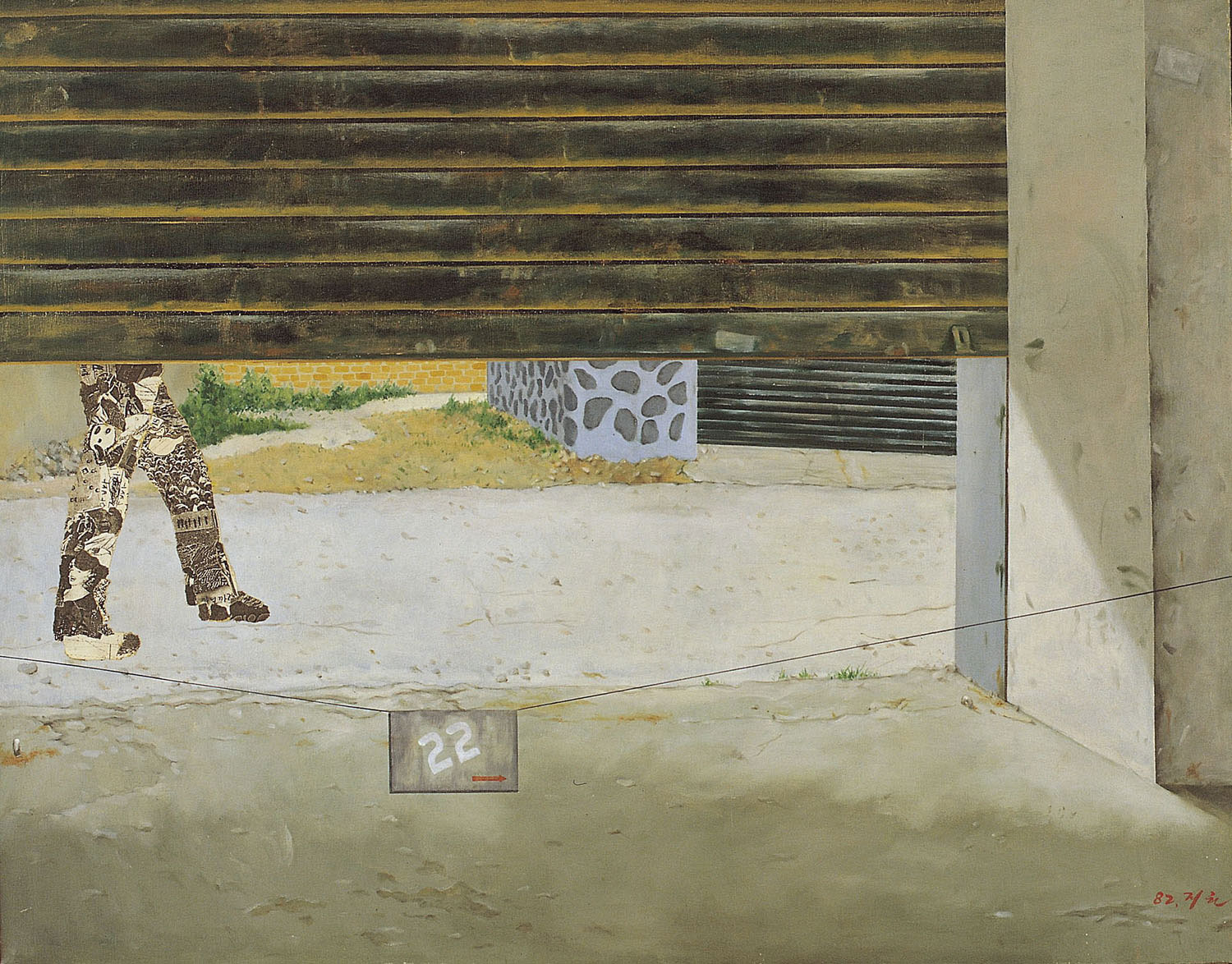

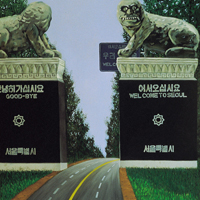

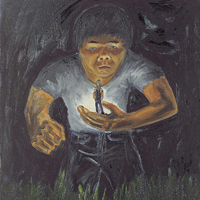

The subjects Kim Jiwon paints on his canvases are familiar and related to daily life. The Mendrami (cockscomb) theme, which Kim has pursued for the past 13 years since 2002, began when he was deeply impressed by the sight of some cockscombs during his visit to a small branch school while travelling in Gangweondo in the early 2000s; and the studio, living room, wall and ocean scenes appearing in the series Take off, Landscape and Daily Life are subject matter that are worthy of note. The tendency to choose surrounding environments and objects to paint is shown already in Kim’s early works. In the series Some Story (1981-1988) and Psychological Icon (1988-1996), the artist painted with composure the gloomy situation of society as he witnessed it at the time: a soldier wearing a gas mask standing in a desolate street, a night scene viewed from inside a house, a torn family photograph, an empty gray underpass, and a tank in the street. While previous critiques have mentioned that Kim was oriented towards social and ethical messages in his early years, and that later he painted in order to receive the messages brought to him by the process of selecting objects and painting them, an additional characteristic that consistently appears in his works, besides the change in subject matter, is that he has remained faithful to “seeing” the surrounding situations or daily objects he faces, and has captured them on his canvases.

Kim Jiwon’s continuous inquiry into “seeing and what is shown” led him from social phenomena to indoor landscapes, and to still life. Sometimes he would blow up small, everyday objects on large-size canvases, causing confusion as to their original shapes and functions. The change in his subjects of painting made his works a little more elaborate and solid. The artist focuses on delicately revealing the characteristics of the subject itself, rather than communicating social messages; his goal, however, is not the faithful depiction of that subject. Thus, those who see Kim’s paintings become more interested in his intention and attitude than in the significance of the subject matter per se, and furthermore begin to chase the “relation” between the painted subject and the artist’s intention. The process of tracking down the essential questions and answers related to the reasons and motivations for the paintings becomes the key to understanding Kim Jiwon’s works.

Painting, the oldest genre of fine art, is a plastic art in which shapes are painted with various lines and colors; basically it takes the form of a two-dimensional plane called the canvas, on which paint is applied. The unique essence of painting is that it always depicts the three-dimensional world, including all matter, on two-dimensional material. According to British artist David Hockney, a two-dimensional plane can be replicated easily within the second dimension, but transferring the third dimension to the second is not easy and requires many decisions. The relationship between the representation and the represented, or the act of painting and what is painted, consists of language, codes and connections unique to the artist; thus, clarifying this relationship provides important clues to understanding contemporary painting. That is to say, as stylizing and interpreting the third dimension is the task given to the artist, the artist’s state and thoughts with regard to this transformation process, i.e., how he reduces what he sees or remembers into two-dimensional language, is important. Kim Jiwon disregards depiction, selects parts of landscapes and objects, and applies methods of omission and exaggeration to them. For this reason, the world in his works does not exist in reality; he forms a world that cannot be defined exactly. In fact, Kim’s works do not show clear depiction, but evoke a particular atmosphere. For example, looking at Mendrami close up, we see thick paint covering the canvas, and lines of unidentifiable shapes overlapping one another, forming lumps of paint before our eyes. But as we step back, we find the shapes gradually becoming clearer. Kim Jiwon’s paintings, which are simultaneously representational and abstract, and which instantly inform us that the painting is an illusion by stacking paint on the flat surface, express the futility of pictures. Mentioning the flatness of painting in a roundabout way, saying “an artist must look at the side of the picture,” he stresses that painting is by no means reality. That is why those who view his paintings become unable to see the mendrami as just mendrami, or the sea landscape as just the sea, but accept the painting through the accumulating, endless slipping of questions and answers between the viewer and the work. The artist paints what he sees or remembers; the spectator sees the completed picture. The effect of the painting, which consists of the circulatory structure of seeing—painting—seeing, strengthens the link between the work and the viewer.

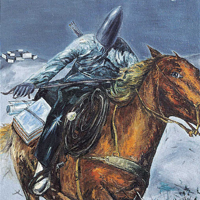

Revealing the World

For the sake of work that reveals the chosen subjects through a unique language on a two-dimensional surface, Kim Jiwon has discarded depiction, using a method that enables the viewer to perceive that it is merely reality on the canvas. After selecting a subject, Kim undertakes thorough observation and analysis in producing the work; the inquiry on painting he pursues is not a discussion of grand discourse clarifying the formal essence of painting, but the attempt to present his own methodology and solution while studying the essential issues of painting—“what is to be painted, and how?” Moreover, his “painting” does not stop at simply representing what he has seen, but reveals what is hidden and the world we live in, through a proactive process of narrowing or widening the distance between the subject and the artist. He contemplates on human life through the mendrami (cockscomb), which blooms brilliantly only to meet a gruesome death; represents his inner feelings through scenes of the sea; and comments on social contradictions through similar walls. Specifically, in the Landscape (2002- ) series the artist is said to have wanted to paint not the waves, but the wind that made the waves move. What is the wind? It is something of which the substance can be identified only when it meets with another object, and something that can be felt but not grasped. The artist once said, “Painting is a challenge toward the impossible,” but ultimately he painted the wind through the concrete object called waves. To Kim, painting is like the wind. It is futile, as you think you have it in your hand when you are painting, but the next day you realize your efforts were in vain. The artist’s peculiar painterly language, which talks about painting while painting the wind, is revealed likewise in his other works. The Take off (2003- ) series, which was inspired by an empty runway the artist encountered while travelling, evokes the indifferent flow of time, and the expectation and uneasiness related to future destinations. By presenting the specific place called a runway for aircraft up front, and introducing the gray runway or traps, which actually play a supplementary role, as the main subjects, Kim subtly reveals the strange atmosphere manifested by the space. In the Similar Wall, Same Wall (1999-2008, 2013- ) series, the artist directly shows the state of poverty represented by crude landscape design, crumbly hunks of rock, and uniform walls of apartment complexes, through which he attempts to demonstrate the uniformity of modern society; these practices focus on exterior looks rather than internal stability, and the self-aware but never-ending desires of humans. Kim Jiwon’s most famous series, Mendrami (2002- ), is a result of the artist’s planting cockscombs in the yard of his studio, and painting them daily from dawn to dusk as they bloomed and fell according to the seasons. The long period of time he spent observing and breathing with the cluster of mendrami in bloom outside his studio served as a momentum for the significance of mendrami to be extended and transformed from a simple flower to the life of a person. The stories of joy, anger, sorrow and pleasure experienced by a single living thing, the brilliant blooming and slow decline, occasional experiences of wretchedness, moments of inevitable compromise with the world in order to survive, the unavoidable dirtying, wearing and ultimate death are told through the mendrami. The limitedness of time, in which splendor is momentary and one cannot but face the flow of time, can be confirmed through these works. That is why as we look at his countless mendrami, our gaze rests upon the crushed and withered flowers more than upon those in full bloom; through a painterly process the link between the work and the viewer becomes more solid, and the spectator reflects upon his/her life through the work.

Kim Jiwon’s works, which talk about painting while painting the wind; and which discuss time through a runway, society’s uniformity and irrationality through wall images, and the ups and downs of life through cockscombs, are realities that exist only on the canvas but nevertheless hold within them sharp insights into this world. An artist must ask lucid questions about what he is seeing. The perceived image enters the brain to be stored as memory, and is then communicated through the artist’s hand. Considering that one of the objectives of art is to make people see, to attract our attention and enable us to see things we would not otherwise, it is evident that Kim Jiwon has been consistently loyal to the role of the artist, as he has chosen and painted things that can easily be seen in everyday life but are often missed.

Wall of Painting

If someone is given a white piece of paper and asked to draw a picture, he/she will, at least for a moment, experience panic. The artist stands before the empty canvas, thinking about what and how to paint, and consequently unfolds an infinite world between the canvas and him/herself, allowing the painting to release its full charm. Painting, the oldest genre of art in art history, continues to flourish today. It has attempted change and expansion through combination with new genres. Regardless of such trends, however, Kim Jiwon has stubbornly stuck to traditional painting for the past three decades, continuously capturing surrounding objects and environments on his canvases through a process of persistent inquiry into “(the act of) painting” and “(the completed) painting.” When people talked about the crisis of painting, his only thought was that there was still plenty to paint, and he continued his work with diverse methods and industriousness, creating dozens or hundreds of works from a single subject. In fact, the act of “painting” is truly a daily activity for Kim, and his work is equipped with layers of muscles that can bear the weight of any circumstance, resembling those of a person who lives diligently every day.

Kim Jiwon’s world of work has as many layers as the numerous works he has produced. In the hundreds of “Mendrami,” which have had a longer lifespan than the other series, we can discover the differences present in the various life forms existent in the world, and the numerous walls in Similar Wall, Same Wall are all visually different as well. The artist paints on the basis of phenomena that exist in the world, but inside the canvas there exists a dimension beyond reality. Reminding us of Hockney’s statement, “What is important is not replicating the world, but interpreting it,” Kim comments on the world through painting, and enables us to discover aspects of the world we have not previously seen. While his former works revealed critical messages by painting the dark times of society, his more recent works have completed a wall of painting, as life was blown into them with deeper contemplation and insight. Wall of Painting, Kim Jiwon’s current exhibition at the Daegu Art Museum, is a wall surrounded by painting, the canvases themselves, and the world, which is the subject of painting. This is not a closed-off wall, but a transformable and flexible wall through which one can always pass. The artist captures on his canvases the daily objects and environments his eyes rest upon; the space in which his paintings are exhibited becomes a wall enclosed by pictures; and the canvas becomes another wall containing the world, as well as a place containing the artist’s agonies and contemplations. Through the world portrayed by his paintings, our understanding of the real world will be improved, as we experience the charm of the “painting” genre, which has prevailed for a long time without faltering.

CHOI Jeeah (Curator of Daegu Art Museum)

A revolution in the picture of mendrami

There was an abrupt, or unexpected, element to Jiwon Kim’s 1999 exhibition, The Beginning of Painting – In the Corner. It featured a series of paintings the artist had been working on since 1994 — along with other series of works such as Similar Wall, Same Wall (1999), Daily Life (1995), Heavy Painting, Heavy Landscape (1998), and Different Sizes of Memo Format (1997) — so the declarative use of the word “beginning” was surprising to say the least.

We could interpret this move in two ways. The first is to say that The Beginning of Painting – In the Corner series did not develop independently from Kim’s other series, but emerged from the interlinking and clashing of his other works. The second interpretation posits that through this exhibition, Kim wanted to clarify his determination for a new beginning in his own painting career, as evidenced by the change of direction that occurred in his subsequent works: his previous view of the artist as “realist commentator” metamorphosed into an open-minded approach that allowed the canvas to speak for itself. The resulting work is therefore a product of communication between the canvas and the artist.

Kim’s recent work focuses on the mendrami flower (the cockscomb which is common to the Korean peninsula, including the demilitarized zone between North and South Korea), as well as on super-sized vessels, airport runways, and aircraft passenger stairs. The Mendrami series features oversized mendrami in full bloom, but the individual flowers do not stand out in contrast to the background. Rather, the canvas itself begins to resemble a mendrami. At first, this transformation seems to stem from the size of the subject being depicted. But the hues of green, red, and white entangled on the canvas also accord with individual flowers in full bloom. Starting from an empty canvas, the artist paints, layers and scrapes to add color and texture, ending up with a garden full of blooming mendrami. A scent seems to emanate from the finished work, filling up the exhibition space — not just the scent of the blossom but the scent of the encounter between artist and empty canvas. In other words, Jiwon Kim’s brushwork is

less concerned with creating a visual portrait of these particular flowers, but focused more on

capturing the artist’s own sensorial response to the world as encountered through the medium of mendrami.

“A revolution in the picture of mendrami,

An infatuation in the picture of mendrami,

A viper in the picture of mendrami,

A desire in the picture of mendrami.”

Dae-Bum Lee (Art Critic)

Transparent Wall, Heavy Painting

This exhibition by "artist" Kim Ji-Won is characterized by the fact that it presents the complex and confusing relations existing between seeing and painting today in a very compact and streamlined manner. To be concise, seeing inevitably requires a process of retreating from the subject and creating a distance, while painting implies the inner motive to approach and narrow the distance from the subject. Artists in the contemporary sense in particular always have the intention to connect, mediate and combine the outlook on the world, with submersion in the self, rational relaxation and sensual contact, or visual control and sensuous reaction. Thus, sometimes they "miraculously" create eye-opening passages, by which the visible world can be expanded or overcome, or the depths beneath that world can be searched. But the price of resisting the division of the senses demanded by contemporary life is the serious abrasion of the artist's everyday life. More directly, an artist can damage his/her body beyond recovery as he/she is torn between the visual centrifugal force and the tactile centripetal force penetrating the act of art. The reason artists cannot choose an easier path is because by simply adhering to one side they can become idea producers or skilled master artisans, but cannot say they are actually artists. Hence, a good artist is ultimately decided by how well he/she can withstand the almost simultaneous, rapid movement back-and-forth between seeing well and painting well, without becoming exhausted. Generally speaking, a good artist is a specialist who carefully considers such relations, and a believer in the mysterious reconciliation between the two poles.

In this solo exhibition, Kim Ji-Won decided to become the "camera lens" in order to mediate the gaps existing in painting. To be more precise, he intended to execute the tasks of seeing and painting simultaneously, by becoming a camera, focusing on the function of the lens. The camera-artist "imitates" the camera preferred by ordinary people, rather than the camera with complex and diverse functions used by "art" photographers or documentary photographers. He particularly appropriates the use of the convenient and economical snapshot photograph in search of a route through which the immanent contradictions of the painting may be resolved. In this context, we must note that the subjects of his choice are not celebrated events or figures, but all-too-common wall surfaces. As he paints the walls in a snapshot manner, featuring their non-individuality and absence of environment, and their ubiquitousness in Seoul and other regions, the artist begins to make layers of significance, which are different in each painting.

When they are captured in a long shot from a distance, the positions and conditions of the walls, and the contexts of spatial significance thus derived, generate a critical nuance of the urban environment. Awkward landscaping, kitschy-looking rocks, and a traffic control bar placed horizontally in front, let on that the picture is of the entrance of a crude, uniform, large-scale apartment complex. Here, the walls in the landscape lack the heavy, thick sense of stability that is required. Instead, the lines on the bricks are drawn in a haphazard manner, not even parallel, thus presenting a faulty feeling, like stripes painted on a thin sheet of plywood. Meanwhile, as we run through the paintings that reveal the true aspects of the walls one by one, we can sense the presence of a certain powerful screen. The plastic-screen wall picture, dividing the exhibition space in two, enables us to realize that it is harder than we may imagine to escape from the wall, because of its transparency. That is because even though the screen is indescribably feeble, at the same time it has multiple layers (naturally formed as the shadows overlap with the other wall paintings) that keep appearing no matter how much it is torn, thus suggesting that the walls have become fixed there like a certain environment. This coincides with the pessimism that it would be difficult to destroy the structure of collapse, which is deeply rooted in our society, as the demolition of large buildings becomes a chronic situation. Perhaps that is why the shameless structures of our lives creating such imperturbable landscapes, and the almost surreal desires of deviation bouncing off of them, are consistently sensed in Kim's landscape paintings. To give some other examples, as far back as 1988, his landscape painting of a Haetae statue (A Certain Expression) shown in his solo show, and more recently, his paintings of lamp posts with Rose of Sharon patterns in relief (Heavy Picture, Heavy Landscape series, 1999) partially share this area of interest.

In the picture-planes that approach the walls from different directions, and from close up, the strokes stand out, and the grids, often seen in modernist paintings, are brought into relief. These paintings, however, are mostly too small to be seen simply as homages to flatness. On the other hand, the colors and brush strokes are too neutral to be seen as rejections of painterly flatness. That is to say, it is difficult to find either traces of submission to institutions of material, or parodic language attempting to overcome the field of such power. Instead, the pure visual experience of the impact with the material is strengthened, thus creating room for sensual pleasure at the fingertips, which had been degraded, to be restored. For instance, these close-up pictures bring back the long-forgotten tactile sense of crayons from our childhood. Along with the traces of automatist labyrinths made as the crayon slid across the paper, numerous trills, hesitations and sincerity of the subject trying to control those labyrinths, are "tracked down" from the other side of the memory. In that sense, this series is an insert of the splendid flowers in full bloom of Like Wild Flowers (1991), and overlaps with the green spouts of water being sprayed in Sunday (1990).

Still, it is difficult to say that Kim Ji-Won's paintings are clustered at the edges of painterly extremes, such as criticism of landscapes or landscapes of senses. Rather, Kim is interested in "between" the two extremes. While opposing the visual inertia Koreans are quite used to, such as easy contrast between two poles and dramatic effects, he attempts to fill the in-between with various differences. This is the reason why he paints walls at the same distance in different sizes, captures pictures at the same distance from different angles, and paints pictures of the same distance and angle with different materials. Hence, by creating diverse combinations and permutations among the distance from the objects, the acquired sight, the movement of the body painting them, and mixtures of materials, walls that are similar but the same, the same but different, are formed in countless numbers.

Of course this Similar Wall, Same Wall series was not made according to Impressionist brush strokes, trembling every moment according to changes of light and atmosphere. Nor does it resemble the overlapping still images of Futurists, who have struggled to capture the movement of the subject according to time and the sense of velocity in modern society. Unlike these approaches, Kim Ji-Won's works practice diverse interpretations of the same subject, ultimately trying to re-input painterly flexibility and all-overness. "Seeing through" the wall-pictures filling the exhibition space, we notice that the insides and outsides of the paintings are mixed up, representation and expression are confused, and moreover, the border between illusion and flatness is not as high as we had thought. Thus the artist's pictures themselves become indexes of such flexibility of painting. Kim's works insert themselves one by one between the dichotomies like CT images. By doing so, they hope to give some volume to the destiny of painting, which has become as flat as it can be.

The peculiar dual structure, which appeared continuously in his works for quite a while after he returned from his study in Germany, can be understood in this context. The landscapes, painted rather realistically, and the icons of dark shadows placed abruptly on top, create a certain relationship of tension in the painting. Through the shade of the giant lying on the sleeping city, the once lost metropolitan myth is revived (City―Psychological Icon, 1994), and in the icons of dogs sitting on the road, a surreal feeling is sensed (Road, 1994). Meanwhile, the indoor paintings with human figures reduced to the size of dolls remind us of the legend of tiny people (Indoors, 1994). In this way, though there are differences in effects, the principle of the work, which resembles the light placement of a sheet of celluloid with other images painted on it, is always maintained. Naturally, what is important here is not each of the pictures that are overlapped, but the layer of significance that is newly created between them.

Shadow of New Town (1997) is a work in which such a principle of duality is manifested in the most "abstracted" way. In this work, the picture overlapped on the top is transformed from the previous black icons drawn with oil sticks into decorative flower patterns painted with oils, thereby achieving a clearer sense of depth in the works. This is because the depth is formed not simply by formation of narrative or heterogeneity of material, but by the mutually different ontological layers of painting. In the former case, what fills in the depth is the psychological comprehension of the "reader" or the physical work of the artist, but in the latter case, the historical sedimentation of painting, from illusion to flatness, is what creates the depth. Thus, by acquiring depth in the meta level and multi-layered visibility, Kim Ji-Won's paintings finally become pictures about pictures, as pointed out by many. If so, the meaning of the tiny people that appear in his paintings also becomes clear. In the series Hu~ In the Living Room (1995, 1996), what the small figures are looking at is not the landscape of the living room, but a landscape painting of the living room. The figures, who are viewing the living room space from different angles and distances, like the artist when he was painting his wall series, are nothing but tiny people who have left the world outside the frame and crash-landed in the giants' land of painting. In other worlds, these little people are symbols of the camera, which Kim Ji-Won decided to become, and furthermore, the figures holding cameras in Flood―Taking Photographs (1995) or Searching for Hidden Pictures (1996) are little people painted to have double meanings.

In that case, is Kim Ji-Won stating that the world of painting is more gigantic than the world of daily life by using the analogy of the land of giants? As we know, the comparison between giants and midgets is not about absolute size, but about relative size, and is a particular situation derived to amplify the dramatic sense of contrast concerning size. The midgets who ended up in the giants' living room were cast to emphasize the tremendous experience of the artist transcending the cognitive boundaries of daily life. Therefore, the sighs made by the small people in the painting are directly related to a scale that is impossible to handle, as in the case when we sometimes gasp as we face the great power of nature. In traditional aesthetics, when harmony is lacking between the aesthetic object and the human, and when the human is especially overwhelmed by the object but at the same time tries to confront it, the feeling that takes place is called the sublime. But the discord between sublimity and humans right away demands humans' imagination to fill in the gaps between the differences of size. "With a vast horizon the gaze can extend far, providing room to deal with that infinite visual field with totality, and to be immersed in the diversity of the observed object itself." That is to say, sublimity is the image of freedom. (The Meaning of Modern Art: A Philosophical Interpretation, Karsten Harries, trans. B. N. Oh and H. H. Choi, Seoul: Seogwangsa, p. 72.)

But interestingly, in most of Kim Ji-Won's paintings, the object of sublimity is not great nature, but crude everyday life. In contemporary life, where cities have taken the place of nature, and replicas of previous landscapes are abundant, literally, the city is the landscape and replicas of the landscape are the landscape. So the many artists "with good sense" living there have had no choice but to observe the everyday in the broad sense. But the change in the subject of sublimity does not mean that the experience itself will disappear completely. On the contrary, now Kim is determined to aim at that very daily life with the gaze of sublimity. Consequently, the territory of painting, which had been endlessly decreasing, and the sight of the artist, which had been endlessly narrowing, made a sudden turn, instantly creating a large space with a bang―as if a midget has jumped into the boundary of a giant's land. Within this space, not only the landscape but also familiar objects transform into strange objects, stimulating our senses without end. As represented by the imposing presence of a cup painted in a size measuring about 2 meters (Heavy Picture, Heavy Landscape series, 1998), the still life itself can become a momentum for sublimity. Ultimately, the analogy of the giants' land is linked to the issue of ideology, rather than size, and is deeply associated with the mechanism rather than the simple effect of that ideology. Hence, the artist is more interested in the possibility of overturning the everyday by incorporating painterly experience, than in the ontological supremacy of painting. This is how the airplane (The Beginning of Painting―In the Corner, 1999), which was made by assembling canvases with paintings of everyday landscapes, circles back to make a rather unstable landing in our lives.

The reason it cannot settle down forever is because of the existential weight carried by the canvas. In the Wall series Kim Ji-Won introduces an alien substance called minium as "found material." This substance, which is generally used to coat iron to prevent rust, is physically heavier than paint. The painting, painted with minium, which is heavier than the same amount of paint, confesses the ethical burden of the artist on one hand, and proposes a social role to be played by the painting on the other. These heavy pictures, which are very sensitive to gravity, admit that painting is for those who move slower than the world, and ultimately cannot reconcile with the world. Moreover, they console us that painting is what acts as a preservative of our perspectives, so that one can continue to advance forward while persistently holding on to the lagging position, in an age of dizzily storming images. Perhaps this is the conclusion of the fable that the landscape paintings of walls and the view of the exhibition space consisting of such landscapes is telling us.

Beck, Jee-sook (Art Critic)

The Beginning of Painting―In the corner, along with the things that could have been art

“What is seen on the picture-plane appears to be actual space and objects, but what really exists on the picture-plane is just paint. (...) But let us slowly move to the side. From the side, a picture is merely a vertical line! This is the misfortune of painting, but also the happiness.” Kim Ji-Won wrote this passage in his artist's notes in 2003. At the time, he had been painting the Still Life Painting, Painting series, which transformed trivial and small objects into tremendous scales and surreal shapes through extreme close-up perspectives. For example, a peach seed emits an awesome sense of existence comparable to the photograph of Albert Einstein's brain, supposedly taken after dissecting into 240 blocks, thus creating a still life painting defying common sense and going against the history of style. The earlier-mentioned "paint" and "vertical line" from the artist's notes form a combination as disparate as the "umbrella and sewing machine" in Comte de Lautréamont's poetry. It is difficult to figure out the actual relationship of balance not only in these topics but also in the still-lifes painted by the artist. The paint on the picture-plane and the single vertical line, however, are not objects-symbols Michel Foucault, Les Mots et les choses: une archéologie des sciences humaines, Trans. Gwang-rae Lee, Words and Objects, Seoul: Mineumsa, 1997, pp. 13-14.

intentionally matched up in an unexpected way based on the system of perception called the "nickel-plated operating table," i.e., the system of Western reason, in which the miscellaneous and heterogeneous beings and objects are classified and arranged according to the single order of reason. That is to say, they are not like the symbolic words of surrealist poets Lautréamont and Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud, who experimented with violations against the system, and with nonsense. They are the "real existence of painting" in the mind of artist Kim Ji-Won. In other words, the paint applied to the picture-plane, the side of the paper or canvas―the vertical line―by which the fact that the painting is a thin flat surface can be clearly confirmed, is "the painting itself," which remains to the end, even after the illusion and imagination of painting, mythology and ideology, the disguise and the most mysterious secrets are stripped off.

Of course it is not that Kim is presenting such theories on painting from the standpoint of "stressing" or "exposing" that paintings are nothing but flat objects of reality on which paint is smeared on the surface by the artist's brush, or that they are merely two-dimensional vertical planes on which diverse dimensions of space such as the 3rd dimension or 4th dimension can be realized superbly just through "deception." Such standpoints were pursued by formalistic modernist painting of the early and mid-20th century, and by post-modern painting, which refuted modernist aesthetics in the mid- and late-20th century, in an attempt to expose the objective dimensions of painting―not only the internal dimensions of art, but the social, political and cultural reality. Let us recall the fact that the former concluded in "empty canvases" of abstraction, and the latter ended in "parasitic picture-planes" in which only intellectual games barren of creative images, and images of heterogeneous mimicry were rampant. Considering these cases, it is clear that Kim's paintings belong to neither one. And we become aware that his claims about paintings are not self-referential definitions trying to conserve painting unconditionally in this era of high-tech digital video, which is creating a violent synesthesia of derivative reality effect; nor are they a lax attitude that tries to jam the necessary and sufficient conditions of painting into concepts such as creation without creation, parody, appropriation or de-constructive synthesis. Then what is the Kim Ji-Won painting? And what do the "paint―materiality of the painting" and the "single vertical line―flatness of the painting," which he pointed out as the actuality of painting, become in the artist's individual works? Or, what kinds of different images, concepts, subject matter, and artist's intentions have they put on until now, as they appeared? What we intend to discuss in the following are not clear answers to these questions. They are, however, possible questions with possible answers.

Unclear Mind, Sensitive Body

On the same night I visited Kim Ji-Won's studio in Pocheon to write this paper, I found an email in my mail box from the artist, titled "From the North." There I read the following sentence: “A while ago during our conversation, you said something had become lucid in your theoretical head, but would it have to be lucid? Let us think about this.” I had made that comment while looking at his works at his studio because there was a certain composition of Kim Ji-Won's art that suddenly came to mind. The artist seemed to be feeling uncomfortable with the "theoretical head" or "lucidity." That was what I thought as I read his mail. And while reading that sentence also, to be honest, I felt an uncomfortable doubt arise as to whether I could write anything about the artist or about his works. Meanwhile I thought about what it is that exists in the essence of the art Kim was trying to guard from the clear assertions of art theory or critical language, in other words, the core of the images that exceed/escape from logic or transcend/break away from words. There seemed to be very many, or very few.

In the June 2010 issue of Wolgan Misul (Monthly Art), Professor Lee Young-uk of Jeonju University wrote a text titled "Just Reading Kim Ji-Won's Paintings." As it was a paper for the Artist Review section, it no doubt would have had the characteristics and functions of a critique, but the title included the plain expression "just," and the main text was woven loosely of sentences quoted from the artist's notes, various titles of the paintings, and the random thoughts of the writer. Lee, Young-uk, "Just Reading Kim Ji-Won's Paintings," Wolgan Misul, June 2010, Seoul: Wolgan Misul Co., 2010, pp. 109-111.

The text was almost like "poetry." While reading it I recalled my visit to his studio about two months before, and his email; and as strange as this may sound, I explained to myself that Kim Ji-Won's paintings and Lee Young-uk's text, which "just read" them, went quite well together. That is to say, with a text that resisted or stood guard against the tyranny of criticism that organizes all works into a conceptual framework with clear logic, the Lee Young-uk-style approach was successful not only in maintaining a dignified distance of criticism between Kim's painting and the text, but also in adding an abundance of poetic significance.

The reason I am suddenly mentioning episodes with the artist that may seem private to readers, and personal impressions of another writer's text―in other words, something that is not meta criticism―is not because I am presenting subjective sentiment, or because I want to confess certain feelings. It is just that I have the intention to acknowledge that there is something about Kim Ji-Won's paintings that makes the diverse and heterogeneous motives of their visible surfaces, the methods and effects of painting, elements of sensuous quality and aesthetic experience nullify or burden any attempt of analytic reading, as much as the artist wanted it to be that way, and as writer Lee Young-uk recognized. That is why earlier I asked what Kim Ji-Won's paintings were, and suggested looking for possible answers, not clear-cut answers.

In Kim's recent works, we can grasp the motives of Mendrami's (cockscombs) super-large warships, and airplane traps on an airport runway. The artist visualized these motives not as constituents of a certain significance or part of a certain landscape, but as the picture-plane as a whole, and as the main characters. A field of Mendrami in red and white paint covering a 259cm-by-194cm canvas, a warship in gray and blue paint spreading out its deck straight towards the viewers' gaze, as vast as the plane of the canvas itself, and the trap of an aircraft barely suggesting what it actually is, with various overlapping lines that incise the picture-plane with a monochrome background like a geometrical abstraction... Thus, Kim Ji-Won's motives transcend the role of subject matter or visual elements which are mobilized to communicate different messages or form context, and embody visuality and presentness of sense on their own. For example, the light and tactile senses that poke our eyes and scratch our legs when we stagger through an endless field of overgrown weeds and wild flowers under the mid-summer sun are vibrant in the artist's Mendrami paintings (Mendrami-Cockscombs, 2005~2010). Furthermore, the violent space of infinity we would have to feel if we had to do something without knowing a preset boundary, limit or end―for instance, if we had to find a lost ring in the Sahara Desert, or if we had to run and escape without knowing how far away was the fence guarding the concentration camp, is developed in the artist's warship painting (Untitled, 2009). And of course we must add the airplane trap painting (Untitled, 2009), dominated by a lethargic and weary mood, and the frustrating sense of being that is felt inside a room full of moisture.

The power of Kim Ji-Won's paintings is that they can take subject matter with little aesthetic value, contents with little direct connection to social awareness, and seemingly not much romantic sensibility, and use them to create visual images which recall certain experiences stored in our perceptive memories sensuously and concretely. No, it is an undefinable strength of painting exercised not just by this artist, but also by other artists who painted great works. To explain this power with more corroborative language, it is the power that is exercised through the performative process of line-drawing and brushwork, when the subjects or motives existing in the artist's head in an unclear state are expressed in and intertwined with the sensitive body consisting of paint and picture-plane called painting. Kim Ji-Won's paint-covered brush does not only paint the visually similar. For example, it does not stop at the point of making the Mendrami look "as if" they are in full bloom, or making the ship look "as if" it was floating in the sea. On the contrary, his brushwork materializes an image world that simultaneously stimulates the five senses, which conduct the relationship between us and the external world, and the perceptive experience of the present and mnemons of the past in a monotonous two-dimensional space. Sometimes that process involves stacking up lumps of paint, roughly creating diverse textures of figures, or using sharp tools to nervously tear the skin of paint, drawing sharp depictive lines. What use is it to explain such "sensuous performances of the moment," after the painting is completed, with a language that is not the artist's? But even if it does not have to be lucid, such interpretation of Kim Ji-Won's work will help to define his paintings.

In short, Kim Ji-Won's painting is something that emerges in the mutual linkage between the simple material condition of the actual painting presented by the artist as paint and the flat surface, and the performative power I presented as the undefinable power of painting, in other words, the complicated "impromptu mechanism," which is so hard for us to explain. Against this, one may argue that "it is a story relevant to all those who paint." This seems correct. We must, however, exclude the numerous formalist abstract painters such as Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt, who studied the material properties of paint and the given conditions of painting as a two-dimensional plane as the very subject of their painting. Moreover, Pop artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, who introduced mechanical image reproduction processes into their paintings, also do not belong to that category. Of course, decisively, post-modernists such as Josh Smith and Laura Owens, who "if painting is dead, scavenge around its dead corpse so that everyone can see Nicole Davis, “A New Lease on Painting”, in: Artnet Magazine (February 9, 2005), http://www.artnet.com/Magazine/reviews/davis/davis2-8-05.asp

," and contemporary young artists who paint paintings that conceptually analyze the patterns of conditions of existing paintings, must also be excluded. That is because to them, the performative process of painting is only the trace of a body more lowly than an idea, a tradition to be de-mythologized, or a reference for deconstruction. But to artists like Kim Ji-Won, that is, artists who feel not frustration but pleasure from the spontaneity, uncertainty and obscurity of painting, the force-field of painting in which the paint, flat surface, action and time, wash in like chaos, is "the beginning of painting." The Mendrami series is an exceptional example of Kim Ji-Won's paintings in which spectators can also experience that kind of pleasure.

The Beginning of Painting―In the Corner

In a text written long ago, artist Ahn Kyu-chul gave the following analysis, as he compared the paintings of his younger colleague Kim Ji-Won which were made in Germany during his studies there, with his earlier paintings done in Korea. “Heavy sense of duty concerning a social and moral statement which had not released him for a long time, reservation of difficult questions such as the conflict between what is Korean and what is Western..., his own judgement whether or not the act of painting an object which suddenly spoke to him one day would be an interesting opportunity to look at his existence in this world..., in other words, the paintings were painted not as a unidimensional means of narration to communicate a message in his head to others, but painted in order to receive the message brought to him by the process of painting.” Ahn, Kyu-chul, I Warn the Static Me, Catalog for the second solo exhibition of Kim Ji-Won, Seoul: Keumho Gallery, 1995, no page indication.

Here it is necessary to extract two interesting points. First is the fact that before emphasis was given to the performative process and power of painting itself, noted by me earlier, Kim Ji-Won's paintings had a tendency to narrate social and moral messages. The second is that according to Ahn Kyu-chul, Kim Ji-Won's paintings are full of concrete perceptive experiences, which we can easily encounter at his present exhibition; for example, the Mendrami were at a germinal stage in his works in Germany. Ahn's determination that Kim's direction of work moved from painting as a means to communicate a message to painting that would lead the painter in reverse, would have been a sharp analysis at the time, and still is an interpretation which completely embraces the peculiarities of the artist's paintings. I have already given a critique of Kim's recent works of the 2000s based on such a perspective. So that part to look into now is the work of Kim Ji-Won which was unfree from social or moral statements or messages.

Perhaps the work that best fits this classification would be Is Your Way to Work Pleasant (1987), which he painted during his senior year in college. Under the military regime of the Fifth Republic, at a time when the college-student-led movement for democratization was at its peak, Kim Ji-Won painted three men on their way to work on a bluish morning dressed in white dress shirts, neckties and gas masks. With the direct and uncanny appearance of the gas masks, the painting is visually stimulating, and the artist's message is also read in a stimulative way. While a well-matched contrast is maintained between the struggle for democracy and the struggle for life to earn "daily bread," the artist sent a cynical message to the latter through the painting (and its sarcastic title). At the time, Sung Wan-Kyung praised Kim's painting for its "depiction of the face of an era called the 80s, and the expression of the times." Sung Wan-Kyung, On Kim Ji-Won's Paintings, Catalog for Kim Ji-Won's first solo exhibition, Seoul: Third Gallery & Geurimmadang Min, 1988, no page indication.

But Kim Ji-Won's narrative paintings closely linked to the current times, from Sim Kwang-hyun's perspective, were limited in that "the spacial discharge when body and picture-plane meet, and aspects of thickness and density, are still weak... His paintings are characterized by an illustrative aspect more than a painterly one, and sometimes give a feeling of fables with epigrams.” Sim, Kwang-hyun, The "Unrest" of Painting and Strategy of "Painting about Painting," Catalog for the second solo exhibition of Kim Ji-Won, Seoul: Keumho Gallery, 1995, no page indication.

Though the critical viewpoints of the two critics are different, we can assume that Kim Ji-Won's paintings from the 80s to the early 90s included commentaries of reality, functioned like illustrations, and were relatively weak in achieving an internal sensuous quality as painting.

But rather than arguing with their criticisms, I want to present a third interpretation. Of course, his paintings of the late 1980s, such as Is Your Way to Work Pleasant, and most of his paintings of the 90s, such as Heavy Painting, Heavy Landscape series, which depicted the artificial and irrational daily landscape of the Korean city, the 34×24 series, and the Similar Wall, Identical Wall series can all be read as social commentaries, and approach us as critical messages that use images. But more specifically, in The Beginning of Painting―In the Corner, which he painted in the mid-90s, Kim Ji-Won demonstrates an overlapping structure of "what he wants to say through the painting" and "the actuality of the painting" as the form and the content. Surely, in the illustration-like and fable-like painting―so labeled by Sim Kwang-hyun―the figures are mobilized to build a painting within a painting, i.e., contents of meta-painting. It is the statement that painting is an act of applying paint on a flat surface with vertical edges, and that the space in the three-dimensional painting which seems to go deep into the surface according to the laws of perspective, is only a two-dimensional picture-plane. That is the "beginning of painting," as Kim Ji-Won made performative paintings of perceptive experience by realizing the so-called "painting itself" on the paintings every moment, while never giving up narrative figurative painting. Not all non-illustrative and painterly figuration is necessarily achieved through Greenbergian materiality and abstract form. On the contrary, going beyond such dichotomous determination, I want to say that a third incident of painting is possible, one that was started by Kim Ji-Won's The Beginning of Painting―In the Corner, and completed to a certain extent by Mendrami. This was already an event of abundant perceptive experience which bloomed fully in Gehard Richter's paintings in the 1960s, and an event of image-text overlapped in a highly complex structure in Anselm Kiefer's paintings. These artists acquire phenomena, observation, the situation itself, painting, talking, feeling and experience within the process of painting, with precision, but also at once. Such minuteness of process and determination is also in Kim Ji-Won's recent paintings. No doubt such attitude and strength were built up not from the recent works we first examined, but from The Beginning of Painting―In the Corner, which we finally discussed in reverse in an attempt to find a possible answer through such a long text. The artist once said that "paintings done over of the things that could have been art" were the contents of his paintings, which I would indeed call the "beginning point of the corner (minority) that becomes art."

Sumi Kang (Aesthetician, Art Critic)