Placement, Displacement, Replacement

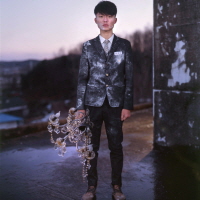

He sets down the camera. On the ground. Colors like the flower of evil emerge from it. The camera absorbs the hues. The camera, as soon as it is set up in exact horizontal and vertical angle, entrusts itself to the vibration and shudder of the colors. The photographer doesn't put much thought into it. He doesn't have to. For the objects think, the colors think and the camera thinks. To press the shutter is only to open the circuit of such thoughts. In the country called the Republic of Korea, there is so much to think about. There are 680 million colors, 13 trillion types of objects and just one kind of camera. The place where singleness and plurality push each other bizarrely and penetrate into one another to engage in chaotic intercourse, that is our homeland Korea. Though the photographer was born in Daegu Korea, now his homeland is the glass focal plane of his 8×10 camera. As someone who has lost his homeland gazes at it from a remote hill with sad eyes, the photographer peers at his aberration of a homeland, which sadly lingers in the focal glass, and gently presses the shutter. As if saying it is going to be a long time before his homeland finds him, the shutter stays open for some 30 minutes. Light, dust and ideas come pouring in hopelessly. What could be done?

When you leave the gate open, welcome guests come in, but so do beggars. As freedom and market economy and prostitutes and the Mob all entered the Soviet thanks to Perestroika, Light, the intensity of speed and fatigue all come at once through the open shutter. But if one is startled by this, he or she is not a photographer. The photographer controls all these elements with the eye of a designer, the shrewdness of a director and the boldness of a Taekwondo artist. Actually he thinks he controls them, but he is just exposing himself before a waterfall of light and colors. But even that needs a great deal of courage. Not many could withstand the waterfall of civilization, pouring out 500 thousand tons of light per hour. To protect ourselves, we have a cord and the horizontal and vertical lines of senses.

The focal glass also has horizontal and vertical lines on it. They mean everything to a photographer. A photograph with misaligned horizontal and vertical angles is a felon who scrambles the order of visual sense and confuses society sensorially and conceptually. The photographer abides by all these rules, while he dreams an impossible dream of escaping from them. He is a complete slave of the mechanism of the camera, but dreams about using that mechanism to fly over the horizon of this world. The disturbance and violence of senses is a typhoon that blows from heaven, but is also the energy that moves his wings. The senses of the Republic of Korea (I will not use the term South Korea) are actually living in a world of strategic array and juxtaposition. The reason the seats in a tour bus looks dark blue is because they are inside a tour bus. The three elements?the bus, the color and the dark blueness?are in no conspiracy, they coexist while sweating from a strategy of secret mutual observation. The reason people say such colors and patterns are corny, is because they are sweating. As the Korean saying goes, noblemen never run. The camera of the lost homeland observes everything slowly and carefully like the slow footsteps of a yangban (nobleman). Of course, this will not make the homeland come back. The photographer just wants to measure the distance between his lost homeland and the place he stands now. It is far. How will I return? Set the aperture of nostalgia on the camera of the lost homeland and apply the lighting of the wanderer and the photograph turns out unbearably sad.

It is because of the mad dance of the hues, which are paradoxically in touch with death. As Dracula disappears when it dawns, the colors will also lose their hues on account of the light that is making them shine. It is the camera of the lost homeland that allows a brief life for the poor colors who are dancing unaware of this fact.

The carrousel (merry-go-round) which wanders the skies of the world, as a ghost without a destination floats about the underworld, has Venice and Rome on the top of its head. Since when have we been so global? Perhaps it was the change during the past 10 years. In an age where even our dreams and unconsciousness have become globalized, the photographer carefully lifts the membrane that has formed on the outer surface of the global dream and gently places it on the surface of the photograph. But, this unexpected weight! The unconsciousness of globalness assumes the weight of European nobility, dignity and elegance, which do not exist in reality, and experiences a premature flattening of the head. Thus, the ontology of the photographer's photographs seems heavy, but shallow, and light, but tenacious at the same time. Perhaps the dialectic of such paradox is the true essence of Korea. Surely, it would be impossible for a photographer to capture the true essence of Korea. A country is too big to enter the view finder of a camera. Or, maybe too small. Nevertheless, the camera is capable of reading the shadows left by the essence of a country. The essence which people with different eyes or optical devices can't read. The substance that they can feel in their skin but cannot explain in words. It is the dimension that is very global and very local at the same time, and thus causes foreigners to laugh in ridicule, and makes us Koreans feel sort of blue.

So there is absolutely nothing strange about the fact that the Statue of Liberty freely left the sea in front of Staten Island and landed on the roof of some motel in Korea. Someone could surely not be able to call herself the Statue of Liberty without even that much freedom. The freedom to control her own weight with freedom. Of course, here, the freest of all is the photographer. It is the photographer who adjusted the weight of the goddess took her off the motel roof and pickled her in the photograph. What did she do anyway? She only wanted to be free! The contribution of the photographer to national culture was that he took the discourses of post colonialism, post structuralism, political economics, simulacra, etc. which were pressing on the innocent signifiant with their tremendous weight and made them light. While the Statue of Liberty must definitely be seen as part of the net of discourses, the photograph should be seen as just a photograph. All the taker and the viewers need to do is to enjoy the experience of astonishment at the perplexity of the photographic detail.

The perplexity and astonishment serve as an opportunity to interpret everything differently and give a new meaning to things. The details in the photographs are not saved through thought, theory or discourse, but are delivered when they loose the useless weight tied onto them. That is why a few words from a useless critic won't do any harm. As a cow would not feel particularly more tired because a fly sat on its back. In this case, the cow is the large-format camera, and the fly is the art critic. He is of no help in looking at the photograph, but can change the color of the picture slightly through a little bit of interference?In other words, as a mediator or messenger of the astonishing experience.

The History of heavy and light details created by the photographer is so written?through the conspiracy of the camera, the eye and the useless critic. What is to be settled by the critic is if the life and world that surrounds us is really a scene of collision of crazy and clamorous senses, then is the photograph, which observes this calmly, in its right mind. In a state where everyone has lost their minds due to the excessive speed, the photograph (not the photographer), which stopped the velocity, is certainly in its right mind. Adorno said one could not write poetry any more after Auschwitz, but the useless critic says one cannot write poetry after the advent of quick service. In an era where services are so fast to the extent of making our capillary vessels expand, who could possibly sit and read sluggish poetry? Photography takes over its role in an era where poetry is no longer possible. The photograph as the function of poetry in that it communicates in a compressed way. But the fundamental difference between the photograph and the poem is that the former is about speed, a representation of speed and a technique that embodies speed.

Of course the speed includes the speed of opening up the tripod, setting up the camera, pressing the shutter, and reloading the film holder, as well as that of reflecting and analyzing. As the poet has his/her unique vocabulary and rhetoric, a photographer has his/her own unique pace. Only then can he/she not get entangled in the tempo of the quick service. The difference between salvation and sacrifice is the difference between memory or oblivion, and what decided that difference today is linked to the issue of whether the photographer has his/her own unique pace, or speed. Taking the picture is not enough. He must take it in a different speed. In order to do so, he must reflect. Taking the kitsch from the world of hallucination and puting it in a reflective field of visuality is an act of deliverance. Hence, the details in Koo Sung-Soo's photographs should be thankful to the photographer. Of course the details did their best too. All the details in the photograph diligently acted as signifiants without being idle. Even the ones pretending to be signifiant did their best. Capturing such gestures and pushing them into a unique mise en scene started the details talking, by borrowing the voice of the photographer. The clear and blue color of the tour bus seats are talking coquettish pongjjak songs, and the free statue of liberty nobly holding a fake torch in her hand is talking moans and groans from the motel rooms. And of course the carrousel sitting conspicuously on someone's rooftop is talking cheers for exotic yearning for the outer world.

It is a pity that all these words are written not in a loving, but a sarcastic tone. No matter how vulgar the colors, grotesque the shapes and bizarre the settings, they are still all our neighbors. Who said to love one's neighbors. Can we love our neighbors when they speak a different language? If we are to listen to our neighbors who speak different languages, instead of treating them as lunatics, regarding them as foreigners or just ignoring them, what kind of philosophical attitude is required? What kind of transition of thought is needed? Do Koo Sung-Soo's photographs enable such transition, or are they just mockery or sarcasm against such neighbors? Isn't pushing different colors of words in a large format camera and grinding them up into a blend an act of violence against meaning? No matter how much ideology of salvation it includes... In the same way it is violence for my loving mother to force me to go to medical school, when I want to go to art school.

Thus all issues of the photography of Koo Sung-Soo are concluded in how heterogeneity and differences of culture and senses can communicate. After all, isn't it the impossibility of communication that is being declared by Koo's photographs? Do the beautiful seats in the tour bus of the photograph also look beautiful to the consumers? As dirt around the rice paddies are not beautiful nor ugly, but just part of the rural environment, the seats are just the environment of the inside of a tour bus. To an appreciator of elegant tourism who visits Paris and drinks cafe alonge while gazing at the Eiffel Tower, the environment of the Gokseong tour bus would be exotic and extraordinarily corny. When twisting the problem once more, it comes down to what to do about the differences between what I see and what others see in the same object. If there are rivers of class, gender, race, taste and ideology flowing between others and I, what do we do about it? Moreover, what if their is a solid camera standing between us? Should the differences between lowliness and nobility, between crude and refined, or between dreaming and being awake be filled in or left alone? What is the significance of the attitude of nobly placing a want-to-be free statue of liberty on a motel roof, and the act of ripping off its dream of placing within the frame of a photograph? Are we to enjoy the spectacle, or lament it? On top of that, what if the issue of nationality, known as the "Korean" spectacle intervenes? Should we say, we are over our heads categorizing material and ideology, so the state should just step aside? Or, should we let them barge in and make the photograph even more complicated, as if placing another set of silverware on an already set table? Isn't it going too far to demand for the camera to deal with the issue of the state? But if the absurdity that my senses are not mine but those of my country, in the form of superego, how can we ignore the matter? In the end, the issue of Koo Sung-Soo's photography leads to heterogeneity of senses and alterity and reaches the disappointing conclusion that nothing in this world really belongs to me. Before we suffocate from the emptiness, let us quickly take what is ours.

Lee, Young-Jun (Image Critic)