Korean Modern Stories Rewritten through Photography

JeongMee Yoon's new series, which began in 2008, use Korean modern short stories as subject matter. Among the 16 works, which required incomparably enormous effort compared to the previous ones, and therefore demanded occasional rest in between, 11 pieces were exhibited in the show, It will be a better day - Korean Short Stories. There works are re-compositions of scenes in short stories, which demonstrate the relationship between literary narrative and photography. The point of interest is how photographic media, which freezes scenes of a moment, and literary narration, which advances in a longer flow of time, meet. The photograph as a cross-section of time or narrative is a work translated into the language of another genre, thus to understand the relation of the moment and continuation, one must provide a context with well-known text. The Korean short stories from the 1920s to 70s, used by the artist, are common in that they are literature easily accessible through text books, etc. not just limited to literature buffs.

They are not only in school text books, but are also listed as "must-reads" by junior-high and high schools. I also came into contact with these stories once more through a coincidental encounter with books for children. I had formerly memorized certain parts for the sake of examination, but do not recall slowly appreciating the originals. Yoon, who has focused on visual ideology that is activated in various aspects of our lives, such as the issue of gender in the Pink and Blue project, rediscovered something that had been overlooked in the mechanical school curriculum. According to the artist, who read the stories again for the first time since her school years, they still contain a vivid resonance today in terms of plot and details. In the stories, which repeat themselves through difference and repetition, humans' inevitable destiny interweaving the two thick threads of nature and history are engraved clearly. This exhibition reinterprets the gender and class ideology, desire, unconsciousness, humor and satire through the language of photography.

The events and figures leading the narration are stereotypical. The key phrase of the exhibition subtitle, "It will be a better day" emphasizes that the issues are current, unlike old stories such as myths, legends and religious stories that clearly promote good and punish evil. The hardships of the modern-day heroes are issues also experienced by us living today, and as there is no right answer, we only pray that things get better. When past-age stories are produced in contemporary photography, the gap may be minimized, but in JeongMee Yoon's photographs the gaps of representation are clearly still present. The distance caused by the gaps of age and genre are not sealed. The contemporary elements intervening in the photographs of the modern stories have not been eliminated, and scenes where sentences in the stories are re-interpreted in today's sentiment are also discovered. Gaps that serve as passages from that era to this one are made not through fictional continuity but through the difference and gaps. Such remoteness isolates spectators' melodramatic empathy, and reinforces satiric the nature.

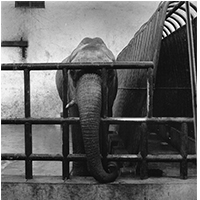

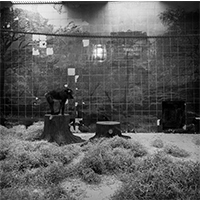

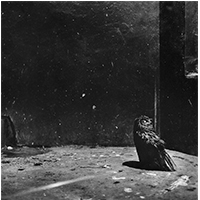

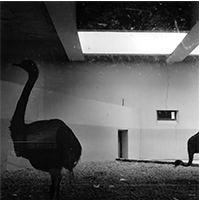

In the modern short stories chosen by Yoon, conflicts due to differences of class or gender are often discovered. The Seaman's Chant 1 and 2 portray a woman who meets death due to her husband who is suspicious about her relationship with his brother. In depicting the dramatic scene caused by misunderstanding, the artist shows a body floating in a composition that resembles that of Ophelia. The work Mountain is about a servant being accused of sleeping with his master's wife, and forced to leave and live in the mountains with nature. The scene of the person blanketed in leaves and looking at stars takes place in a modern park. It seems to ask whether original nature―as clearly shown in the rounded image that resembles a womb and tomb at the same time―where one can return to in order to escape from conflicts in human society, still exists. In the modern short stories chosen by the artist, women appear as victims of the idea that men are superior, and the remaining patriarchy makes the modern man uncomfortable as well. A Society that Drives You to Drink portrays a situation where the husband, who had studied in Tokyo, cannot but spend his days drinking. The photograph, taken in a bar at Pyeongchang-dong, Seoul, shows little gaps between the eras, unlike the other works. This is because the academic inflation taking place in art and other areas as well is a universal problem today in particular, and is continuing to accelerate. The work, Wings, also depicts a highly-educated unemployed husband loafing around in a Japanese-style room. He is wearing a white shirt, sitting on a white sheet his wife must have washed for him before she went to work, and has a silver coin she placed by his head. Tragic love stories crossing over social class is a favorite subject for TV dramas, but there are specific editions for each era. The work Samryong the Mute takes place at the scene of a nowadays disaster, where the love between a servant and the new bride of the master's son burned in failure. At the scene of tragedy, the man and women in Korean traditional costumes are portrayed like the Pieta. Imbecile Adada is a scene of the heroine, who thinks her first marriage failed because of money, throwing away money behind her second husband's back. In the original she does it secretly, but in the new version she spreads the money about refreshingly. Love and marriage affairs entangled in money are so deep-seated they can only rely on a catastrophic end, where liberation and death cannot be determined. The scene, which leads her to death, is produced in a festive atmosphere, and her skirt, the flying money and the sea gulls express the modern woman's desire for liberation.

B Housemaster and the Love Letter shows the comic hysteria of the sexually oppressed old maid. The place where the heroine, wearing a white blouse and black skirt, indulges in a sweet fantasy, holding a student's love letter as if it were her own, is a staff room in a school today. In an age where the number of highly-educated women who reject marriage increases, her hysteria is in progress as well. The work Lecturer Kim and Professor T is a satire on the still existing corrupt practice of bribing someone for professorship. One of the universal issues that have many links with the present is the kind tangled with family relations. But the bond between family members is not what it used to be, and that difference also becomes a message of the work.

Endless Supply of Treasure represents the last scene of the story in which the loving couple who died on account of poverty, and the child who walks between them, were discovered. Unlike the original story, the child is portrayed as one with mixed race. That is because the new form of family called "multicultural" family clearly reveals the issues of families in poverty. In the work, When Buckwheat Flowers Bloom, the field where father and son make their dramatic encounter is not Bongpyeong, but the Citizen's Park on the banks of the Han River in Seoul. The modern urban scenes surrounding the site are left, undeleted. The thickest blood-relationship transcends times.

The work, Stray Bullet, in which the hero, who has a foreigner's whore for a sister and a thug for a brother, appears, is based on the conflict that takes place among family members, who are examples of the era. Though the scene is tragic, the comic figure dripping blood from his nose and the atmosphere of the set prove to be a satire on the family solidarity of a past age. A Lucky Day was taken inside an old flat in order to reinterpret the tragedy of a poor rickshaw man, who lost his wife to the other world on a day he made an extraordinary income. There will be more and more misfortune caused not only by relative poverty, but also absolute poverty.

The Old Potter expresses anger towards his young assistant and his runaway wife, but also feels sorry for himself, who cannot even make a pot as good as his assistant. This scene overlaps with an impoverished artist, who has lost not only his talent but also his youth. From the pose of the disappointed old man, the artist is reminded of Self Portrait as a Drowned Man (1840) by the pioneer of photography Hippolyte Bayard, who had his entire honor taken away from him by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre. The universality, which can overlap with examples of other countries, and is discovered throughout the works of JeongMee Yoon, sets a direction of the work's future advance, not just in Korean literature but also in world short stories. The modern history is also clear. The White Crane deals with the issue of ideology, according to which the hero becomes hostile towards an old friend whom with he had caught cranes together in their childhood. The Suffering of Two Generations suggests that the issues of macro history effecting an individual continues to remain today as the conflicts of capital escalate, through the scene where a father, who lost his left arm in slave labor for the Japanese, and his son, who lost his right leg in the Korean war, attempt to cross a log bridge together.

Short stories penetrate the photographs of this exhibition from the beginning to the end, in terms of both content and form. Yoon's photographs, however, do not represent the stories as they are. That is not possible or preferable. The artist's goal was to make new photographs with new stories by utilizing the common aspects and differences of both genres as much as possible. A novelist can see a photograph and a visual artist can read a novel, but in an era where each medium has evolved into a state of divided labor, each medium is nearly illiterate in how the other medium's language is expressed. Thus, it is easier said than done, for someone to traverse genres. One must know at least one language for certain. To the artist, who majored in painting at college, but then spend more of her career in photography, traversing boundaries became an experiment to achieve something new. But first, we must examine the short story, which was the starting point of the works.

The dictionary definition of novel is "a fictitious prose narrative in which the writer tries to generate interest through the depiction of passion and customs, or through the peculiarity of the adventures." (Littré dictionary) Moreover, a novel is "a prose of significant length written from imagination that presents characters as if they were real, and lets us know their mental state, destiny and adventure." (Robert dictionary) In Origins of the Novel, Marthe Robert brings out the existence of the novel from "as if." JeongMee Yoon's works, which are based on short stories, also begin from reality, according to the method of "as if," but the heroes completed through imagination are used to rediscover reality. According to Robert, a novel is characterized by essential contents and undecided form. As the original stories were completed through the complementary relation of fact and freedom, the photographic producer and spectators also have room for free interpretation, besides the given facts.

Yoon does not rely on the theological and romantic image of the artist, known as "creator," but accepts the role of re-weaving existing text. Though an era has arrived where a photograph can escape from its own index and be made freely like a painting, there is no need to give up the positive nature of photography. The artist fully discloses the original text, mobilizes concrete characters and places, using current resources to recompose the scenes as realistically as possible, which is in fact a strategy to use the positive power of photography in the communication of a universal message. Meanwhile, she leaves spaces and gaps for new creation to take place in what already exists. These are gaps of the eras and gaps that occur from the difference of genre―short story and photograph, but in a broad sense, this present the possibility of new interpretation and writing. The artist demands the spectators (readers) not just to consume through reading, but produce through writing. The direction for the primary meaning is presented through the clearly revealed sources in the titles of the works, however, the spectators are given the tasks to organize and compile each completed part into another whole.

The spectators are universal humans, who are living now with their entire bodies, as whole as those did back then. In this exhibition, there is a common aspect in contents, besides the combination of the most popular and universal arts of modern times―the short story and the photograph. Another link between the two genres is that both forms can deal with infinite variety of subjects. According to Origins of the Novel, in general the novel is considered as a descendent of the great epics of the past, but the novel as we use it is a relatively recent genre, which only has a very loose relation with the tradition it came from. The modern novelist observes, compares and measures, in other words, he simply replaces faith with critical spirit, and replaces eternity with the confusing reality of the times. Yoon's works, which connect modern literature and contemporary photography, are also criticism of the confusing reality open by modernity.

The modern short stories in the works are fictitious, in other words, fake but may take place. Such happenings are not just in the past, but still take place, and may continue for a significant period of time. Here, reality and fiction, universal and special are very close with one another. In Time and the Novel, A. A. Mendilow divided the relation of truth to life, which can also serve as criteria for novels, into the following four: the impossible, the improbable, the possible and the probable. According to Mendilow, novels have excluded the first two from its territory from the beginning. He claims that great novelists only write within the boundary of the fourth item. Novels present relations of the affairs that pass before our eyes every day, or things that may happen to us or our friends.

Yoon's works demonstrate that the modern short stories that served as subject matter significantly reflect the history of the times, that they take more dramatic appearances as social conflicts of class or gender emerge increasingly during the rough periods of modern history, and that today's conflicts, which seem to be too hardened to change, take a more original form as they are placed in retrospect to their origins. They also demonstrate that these are also issues still in progress. The resonance created between now and then has been an important motivation for producing the works. Those called to be heroes for the works were ordinary people―people who were constituents of democracy, which was still undergoing experimentation as an unknown value. Mendilow points out that in early romance the world is full of royalty and later they change to nobility, however, middle-class or lowly heroes are almost impossible to find in pre-18th-century sincere fiction. Among the unfortunate people appearing in Yoon's works there are some upper-class characters, but these are usually supporting actors and not the heroes. They usually appear in a weak state, unable to enjoy their original status.

In the sense that it was the modern time that the readers of novels and spectators of photography became universal, the issue of universality echoes throughout Yoon's works in many dimensions. An era where the large-scale tradition collapsed but new order was not yet established, and the universal lives of people who lived that era with their bodies comes to us in both chaos and vitality. Such duality emerges not only in tragedy but also in comedy. Most events that took place during times when poverty was devastating, but when that is compressed into a single photograph―the original stories enter a mis-en-scene established through photography, and in JeongMee Yoon's work, which actively introduces the element of time called the narrative, there are theatric elements of contemporary art overtaking modern art through similar choices―the two sides coexist. Such duality presents once more the issue of reality and fiction.

The spaces and gaps, which are left intact in JeongMee Yoon's works, are to give room for another fiction. The method of imitating reality in order to make someone believe the story is the two dimensions (reality and fiction) not only in the original novels, but also in the photographs. Marthe Robert stressed that a novel is neither real nor false, and that the truth of a novel is nothing other than the increasing power of its fantasy. According to Marthe's Origins of the Novel, the expression "making a novel" is "capturing the heart of someone with conditions better than in a novel," and "telling a story about something, unlike what really happened," while quoting the Littré dictionary. Lies specially made up in order to bewilder are no flaw in a novel, and fixing it would belong to the freedom of the novel. That is because even though the reality is something the novel will never reach, by symbolically presenting the realistic desire to change reality, the novel is always in touch with reality in the decisive moments.

The writer combines lies with the truth, and mixes what is realistic with what is imaginary. The ability of a novel is not in the ability to represent reality, but in the ability to carefully examine life in order to endlessly re-create new conditions for life, and re-distribute elements of life. Yoon's works, which are make-belief but plausible, demonstrate that the relations established between fiction and reality in novels are also in photographs. Her works, which do not try to hide their fictitious nature, reflect the reality or the stories, and play with them at the same time. The power of the two genres of art, which influence readers and spectators through fabricated acts, is amazing. The power comes out of not only the narrative, but also formal custom. Mendilow thought that through the customs of the novel, writers could establish basic hypotheses, and the willing readers would successfully create fantasies in their minds. Thus the novel is a product of intimate cooperation between the writer and the reader.

In art, reality does not exist transcendentally, but is always re-made. Time and the Novel brings the issue of artistic custom into relief while saying that "realism is something artificial, distilled from the fruit of the minutest observation (Thomas Hardy)," and "as long as the novel is doing nothing but imitating, it is not imitating life, but imitating words. It is not imitating humans' fateful reality but imitating the stress and restraint that takes place when the actor called the human tells the story (Stephenson)." Since literature is half the truth at best, but still tries to communicate the illusion of the complete truth, the novel completely relies on keeping the agreement made between the writer and reader of "pretending." A paradox exists here, that one is fooled as much as he believes, and believes as much as he is fooled into. This demonstrates that for a work to have effect, a perfect formal device is required by the photographer, as much as the precision literary style of the novelist. Through this the non-linguistic experience can be turned into language, and the linguistic experience can be reinterpreted into a non-linguistic form.

Sun-Young Lee (Art Critic)

more

The Chain Reaction of JeongMee Yoon's Controversy of Color: Blue Girl and Pink Boy

It was after democratization took place in the late 1980s, after doubt began to overshadow the realms of sense and meaning, that the authority held by the meanings of all things began to shake in Korean society. Following disputes over things that used to be only natural, a controversy over "color" broke out. Of course even in the 80s, before the democratization, there were controversies of color concerning political ideologies, but it was not until the 90s that such controversy reached as far as to implicate presidential candidates. Ever since, as liquid seeps through the fabric of hygienic bands, the color controversy penetrated into the finest pores of society, causing people to question the colors of others' clothes or what colors were used to paint buses. It was 1985 when popular singer Cho Young-Nam complained at a discussion at the Seoul Museum of Art that all the cars in Korea were either black or white. Perhaps it could be called a feeble beginning of the color controversy, outside the boundary of politics. Shortly after this event, the city buses of Seoul were painted in purple. The color, which was said to have been designed by a Hong-ik University Professor, was changed after receiving tremendous reproach from annoyed citizens. Even the mighty university professor was helpless before the color controversy raised by the people. What was the reason for this? It is because color itself is political. As it is quite bothersome to explain why it is political, I hope all sensible readers will understand it on their own.

Now, photographer JeongMee Yoon engages in a color controversy through her photography. In our society, the controversy of color has expanded to the most microscopic dimensions. It is somewhat frightening to think that someone's ideology or personality could be judged by the color of his/her fingernails or pulmonary valves. Moreover, JeongMee Yoon uses a dichotomy that could either save or kill a man. Perhaps the reason that we are keen about seeing the outcome of the perilous situation, in which a sharp and heavy nippondo (Japanese sword) is placed on a person's head as if one was about to slice a cherry tomato, is because we are not so interested in the life or death of the person. In any event, Yoon's color controversy is quite simple in structure, but intricate in connotation, leaving a long lingering aftertaste.

This is how she does it. She divides children's rooms into two. Blue or bluish items are placed in the boys' rooms, while pink items are placed in the girls' rooms. The children are photographed sitting in the middle of the rooms. They are positioned in the center of the room, as if they were responsible for the color of the objects surrounding them ― the color of the superego which decides their gender. It is rather excessive for the photographer to place such weight on the innocent children. It is like telling a person driving a Jaguar, "Since your car is a Jaguar, you are also a Jaguar, and therefore you must catch a deer and eat it raw." It is a tyranny of signs. After all, the car is only a metonymy of the actual jaguar.

What happens if there is a tyranny of signs? Ironically, the true nature of the signs are revealed. Similar to the way a particle accelerator is used to charge corpuscles with tremendous energy, enabling scientists to find the origin of matter through the traces of fragments from the ultra-high-speed crash of the particles, JeongMee Yoon confirms the heavy and sticky order of colors and senses with the children through a tyranny of signs that forces the kids into being the main characters of their given surrounding colors. Frankly, the children do not want to know about such facts, but the order has been prepared long before they were born, and even if some enlightened parents buy tanks and swords for their daughters and flowers and hair pins for their sons in an attempt not to raise their children as stereotypes, the children will demonstrate remarkable wisdom of selecting the stereotypical colors predefined by the superego of society on their own as if they were being led by some sort of centripetal force.

However, the photographs of Yoon, which look quite organized and scientific, are in fact very fictional. The classification of Girl-Pink and Boy-Blue was a result of a certain organizing. The reason they are fiction is because the order of senses in the world is not so clearly cut. Even if things used by children can be categorized according to the colors preferred by the genders, there is always a gray zone. There is even a buffer zone between the Northern Limit Line and the Southern Limit Line of the DMZ that splits Korea in two. Thus, I would like to call what Yoon created, a "virtual stereotype." Actually, what we need to observe in her photographs is the intersecting point between the conceptual setup that clearly divides the objects, and the photographic execution of taking the pictures with the children in the middle of the rooms filled with the objects. At that intersection, the visual order of the colors and the photographic order cross paths. Could JeongMee Yoon's message be that there is such a solid order in the world? If so, she is a silly photographer who goes through the effort of taking all that photographic equipment all the way to America to photograph a kid's room scattered with all his/her belongings just to tell us again something everyone already knows. If not, what else could there be?

But if one sees only the tight order of objects and dichotomy in Yoon's photographs, they are missing the whole picture. The intersection is not an area dominated by a single order. All the pink items are not the same pink, and the blue items are not the same blue. All the children's belongings are slightly different pink. They only look the same because they are placed in the singular and abstract category of "pink." As we have a habit of always thinking in categories, we tend to classify things simply, such as "pigs are all fat," "the South Pole is always cold," etc. JeongMee Yoon's photographs use such habits to acknowledge our worldviews and make us feel comfortable. Yes, children are only children, so where could they possibly go? They can only play in the garden of stereotypes made by adults. But such sense of relief shows small but terrifying differences between its pixels, because nothing in the world is identical. The only things that are the same are abstract categories. No objects or senses filling up those categories are identical. This world is full of differences resisting against order to the extent of horror. Even the pink plastic spoons owned by Emily are not the same pink, though they are all industrial products. They all look different according to where they are placed and from what angle the light hits them. Like an ancient Greek philosopher once said, "you cannot put your hands in the same stream twice," the same object cannot appear in two different locations at the same time.

In the matrix that is formed between objects, there are holes made by the large and small differences, and though Yerim's shoes are pink, they are in fact all different colors. Even the left shoe and the right shoe are not the same color. The irony of the pink and blue are deeper than one may think. So saying that boys only like blue and girls only like pink is as dangerous as saying Koreans all look alike from a distance. Nevertheless, we are actually accustomed to such conventionalism. We make gross generalizations such as the Germans are diligent, the English are gentlemen, the French love culture and art, and Arabs all look alike―the kind of generalizations that could get our heads chopped off with a Saif.

Hence, if the artist's intention is to reconfirm a very simple stereotype, she does not need to undertake such complicated work. She can just ask people what colors they like and announce the resulting statistics according to the categories of gender, occupation, education, dwelling areas, etc. Perhaps the work of JeongMee Yoon indicates that color has no meaning? Let us extend the color controversy to food. The significance of color in this case is extremely arbitrary, for instance, just because a food is a certain color does not mean it tastes a certain way or is given a fixed significance. Are red peppers hot, or green peppers hot? According to our stereotypes, the red ones should be hotter. But in reality, from Mexican jalapenos to Indian chilli and Korean Cheongyang peppers, the really hot peppers are light green. Let us look at Coca Cola and jajangmyeon (Chinese noodles). The color of Coke is dark brown, which is not so refreshing. Furthermore, the logo of Coke is red, which is also unrelated to coolness. But that does not mean that the hot and heavy colors of the drink make people sweat in the summer days just at the thought of it. In fact, it is the opposite. How about jajangmyeon? This is also dark brown. It is a dark, sticky and oily food. But no one despises these noodles because of such aspects. On the contrary, jajangmyeon has received everlasting affection from the majority of Korean people. This means that color is not an absolute signifier. Color is an innocent signifier that has entrusted its body to the diverse functions of signification. It is the humans who take those poor colors and frame them with all sorts of nasty connotations. Color itself has no meaning. This is the simple truth that I insist.

JeongMee Yoon's color controversy catches on cold fire. Who gave blue to the boys and pink to the girls? Was it their parents? Was it society? Was it the school? Was it a neighbor? Was it a friend? Or was it the obscure but powerful custom and superego known as the distinction of gender? Will the same colors be given to the children to be born in these children's rooms in the far future? Will the children in the center of their rooms filled with pink or blue objects act as superegos of the next generation's children, or deny themselves and mix up the objects, placing themselves in a gray zone of colors? A more fundamental question is must there be a distinction between colors? So what if it is blue and so what if it is pink? After a long struggle that lasted for over 50 years, our society has been barely able to escape from the red complex, except for a small part. Now shouldn't it overcome the more elaborate and sneaky complex of tying pink and blue to certain genders? JeongMee Yoons controversy of color seems to exert that the realms of pink and blue are clearly divided, but for some reason I feel that it is directed towards the more radical question of "what use is it to make divisions between colors?"

Supplement

Pink Floyd and Blue Note

When I was little and first heard of the Pink Floyd, I thought it was a group that did soft and mushy music because of the feeling the world "pink" gave me. After knowing that their lyrics contained wretched expressions about all the wounds and pains in the world, the color pink began to look completely different to me. Actually, pink is a contagious sign, which could give a twang to any word it accompanies. But the Pink Floyd had nothing to do with the color pink. The word "pink" was just a tribute to blues musician Pink Anderson, who was worshiped by Roger Waters and Syd Barrett―early members of the Pink Floyd. Some get confused between the Pink Floyd and the Pink Lady. Fortunately, the two "Pink"s are both musical groups but have nothing else in common, and therefore leave no room for further confusion. It is a good thing that the connotation of the color pink did not penetrate into the music of the Pink Floyd, who made sad and beautiful songs about the contradictions and wounds of the world. That is why we do not easily get tired of their music.

The most famous jazz club in New York City is the Blue Note. The club is very popular with Japanese tourists, to the extent that they call it the mecca of Japanese tourists. The Blue Note is so famous that while there is only one in New York, there are three in Japan―one in Tokyo, one in Osaka and one in Nagoya. When I went to the club, a funky atmosphere of the Japanese tourists had been dominating the place, rather than a pure and cool feeling of blue. I never went back to the Blue Note again. It would perhaps be more honest for the club, which is attracting tourists with the force of blue, to change its name to "Pink Club." The Blue Note: how irritating!

Pink Lady Falls into the Blue Ocean

Japanese girl's duo Pink Lady, which created a sensation in the early 1980s with its sexy concept in Sexy Music and Kiss in the Dark, could perhaps be seen as a predecessor of Korean singers Lee Hyo-ri and Seo In-young. Now the name only remains as a flower shopping mall, a drama title, the name of a cocktail, and a device for masturbation. The group which has been long forgotten and is hard to find even on the internet, however, has managed to clearly engrave the connotation of "gaudy and vulgar" on the word "pink" through its songs. I recall that the Hee Sisters, Suk Sisters and the Gukbo Sisters, who were active during the same period, could not match the Pink Lady in its "pinkiness." As I listened to a pirated edition of their music that someone had bought for me for 350 won, I was surprised that music could be so shallow and vulgar. Then I was surprised once more at the fact that more than 20 years later such shallowness and vulgarity could reappear in Korean singers. History repeats itself, and so does pink―once as the color of a Korean traditional shirt, once as a song with a sexy concept, and once as the color of lipstick.

Now pink is no longer the blue ocean. Except for a very limited area of taste, pink does not sell. In the 80s the Pink Lady may have swum in the blue ocean, but in the 21st century they have fallen into the blue ocean and have drifted away to an unknown place.

The Pink Panther and the Blue Impulse

I have never seen the Pink Panther. I just thought the title was sort of peculiar. The Pink Panther was a popular series of detective movies which was produced from the 1960s to the 1980s. There were eight series in total. The production gave birth to the famous actor Peter Sellers. In the first movie made in 1963, "Pink Panther" was the nickname for a giant diamond. The story is about a thief known as the Phantom trying to steal this gem. The Pink Panther acts as a mascot, who appears in the beginning and the end of the film, serving as a symbol of the funny happenings in the film. The Pink Panther was later made into a separate TV animation series. It is said that while taking a bubble bath scene, the staff used strong chemicals to make more bubbles, resulting in injuries on the actors' and actresses' skin. Robert Wagner, who had to dive into the pool of bubbles, suffered from temporary blindness that lasted for four weeks. However, it is only the title that is imprinted in my head.

Watching the Blue Impulse―flight demonstration squadron of the Japanese Self-Defence Force―flying smoothly with their Japanese-made T4 trainer jets, I feel envy as I wonder when Korea will be able to form a flight demonstration squad with jet fighters made in Korea. The Blue Impulse was first founded on March 4, 1960 at the Hamahatsu Air Force Base with 5 F-86Fs. It made demonstrations at the opening for the Tokyo Olympic games in 1964 and for the Osaka Expo in 1970. Following the introduction of Japan-made T-2 jets, the squad now operates eight T-4s. The name of the squad most likely takes after the US Navy flight demonstration squadron, Blue Angels. To a flight demonstration squadron that engages in beautiful but dangerous acrobatics, blue is an appropriate color to express the perilous fate of the pilots who must perform on the fine line between life and death. Pink just doesn't seem to go well with death. As I am writing this paper, I suddenly hear on the news that a Blue Angels' plane crashed, killing its pilot. Blue is the color of bruises.

Out of the Blue

In English, the word blue seems to have more negative meanings than positive ones. In Korea, blue is a refreshing and clean image, but in English, blue basically means depression. It also could mean desolation. "Out of the blue" means "all of a sudden without warning," or perhaps, as a Korean saying goes, "like catching and eating a rice cake in one's sleep." The phrase probably came to be because of the absurdity involved in a case where something suddenly falls out of the blue sky. I suppose the custom of boys preferring blue and girls preferring pink came from the phrase, "out of the blue."

YoungJune Lee

more