Sang Hyun Lee, The Museum of Photography, Seoul

Birth

1954, Seoul

Genre

Installation, Photography, Media

Homepage

The Eternal Return

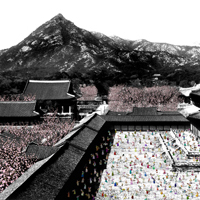

At first glance, and especially to the outsider-Westerner, Lee Sang Hyun’s recent photographs and videos may simply evoke stereotypical cliches of a highly technical, hybridized, contemporary Korean society: they are works that seem to perfectly blend with the hyper-reality of a world characterized by a profusion of images, symbols, ideas, and concepts of a society that went through brutal changes in the last hundred and fifty years. The Korean modernization process has, in fact, been extremely rapid, even violent in some aspects, taking the country from the third to the first world in just one generation. Not only has there been foreign occupation and wars, but also a total collapse of traditional culture and way of life under the impact of Western civilization. Most of Lee Sang Hyun’s videos and photographs seem to completely personify this. Lee’s digitally montaged imagery is made in vivid, bright pop colours depicting fictitious and historical scenes, juxtaposing past and present, the West and the East, nature and industrialization, rational and irrational, mass culture and traditional landscapes, good and bad, male and female. Many histories and mythologies, including the artist’s own, are intertwined but there is something more than that which meets one’s eyes as Lee himself likes to cross boundaries and go beyond traditional dichotomies. Unsolved mystery, nostalgia, dream-like imagery, science fiction: Lee engages a variety of atmospheres to unhinge his pictures from their contemporary reality.

There can be no denying that cultural recycling is a defining aspect of the present era, an era characterized by its obsession with the past. It is true that the need to remodel history is part of the human condition, but the pace, intensity, and proximity relevant to this urge seem to be increasing. For the last half century our recent cultural and symbolic past has been ruthlessly mined and exploited. We appear to be seeking anything as long as it has been done before. Convention makes us define original concepts by comparison with past ones. No trend, whether music or art, is ever recycled exactly. As Nicolas Bourriaud has pointed out, today the boundaries between producer and consumer have been blurred. According to Bourriaud, we have entered into the phase of consuming cultural signs, which constitute our living, collective memory (discs, video cassettes, video games, etc., all available for purchase). The cultural signs that we consume are re-used to produce something new. Culture becomes an entity available for use, a set of recyclable signs, which are alternately the subjects and objects of our experience. Today’s artists dig into the “archives” of our world to create new situations. It is their practice to borrow from all sources. All sorts of experimentation become possible through sampling and reappropriation. The original subsists in a new context?it is less a matter of eliminating the past than of lending new life to old images and recorded signs. Nietzsche’s theory of the Eternal Return suggested that we should imagine our lives not ending at our deaths but being repeated over and over again for all eternity, each moment recurring inexactly the same way, without end.

In this manner, Lee not only revisits the historical past of his home country and of Western culture, but his own past. After a relatively long period of reclusion from the art world, he has decided to come back, incorporating his own experience and frustration in his art practice. Lee started his artistic career in 1988 and by 1995 was considered one of the most important Korean artists of his generation. In 1997 he was invited to play the leading role in a feature film titled Lie (1999), which narrated the sadomasochistic relationship between a sculptor (Lee) and a high school girl. When this controversial film came out, it was banned from all Korean movie theatres and Lee experienced fame, criticism, and misfortune at the same time. He ultimately decided to step back and temporarily withdraw from the art world, to return only in 2004 with a completely new approach to his art practice. Whereas his previous work was mostly installation-based and looked very much into the future, in his most recent pieces he deliberately decided to focus on photography and the moving image in order to explore and depict a ‘futuristic past’; they are mediums, which would most appropriately provide him with the tools to reflect and explore questions related to artifice and reality, to what is revealed and to what is concealed in an image. Self Secession, which was his first artwork after a five-years gap, consists of a series of self-portrait photographs of the artist disguised as a woman and marks a turning point in his career.

Functioning as sort of like a statement, Lee deliberately chooses to confuse the spectator so that she/he questions how images can be manipulated in order to deliver a certain vision of reality. The work is also obviously auto-biographical as it directly refers to Lee’s difficult experience with being taken for the character he played in the film Lies, and to his wish to overcome and escape this false image. The twelve photographs feature the artist sitting with his legs crossed in different meditation positions as in Buddhist statues. Escaping himself was probably a main goal of Lee, after a life drama at a time when he had seriously taken on meditation, a practice which gives one the possibility to depart from oneself and ultimately attain the state of Nirvana, where no boundaries such as the ones of gender or age have any meaning. Of course, any portrait treads a winding path between revelation of the subject and of the artist.

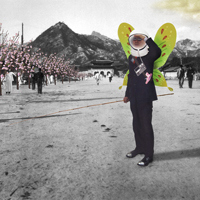

Many artists, such as Marcel Duchamp, Pierre Molinier, Urs Luthi, Bruce Nauman, or Cindy Sherman, just to name a few, have used methods of camouflage and masquerade to question the role of the artist as an inventor of stories and creator of illusions. As in Bruce Nauman’s Art Make-Up, Lee’s self-portraits touch upon topics such as the invention of the other, the re-invention of oneself, the artist making up stories, the camouflaging of reality, etc. Similar to Duchamp’s punning female alter ego, Rrose Selavy, Lee’s masks’ seduce, bid us to come closer while holding us at a distance. Lee therefore uses cover and artifice to reveal more than one thing, more than one man, or better yet, more than one vision of man. In the same spirit, and following his self-portraits, he created in 2005 another photographic series named Little Siddhartha, which featured teenage girls posing in different meditation postures. ‘Siddhartha’, which is the name Buddha used before he achieved great enlightenment, means ‘ascetic’. Siddhartha wants to reach illumination through the practice of meditation but is constantly put off track and tested when confronted with the temptations of the rich and mundane world. Following this setting, the girls in the pictures are heavily ornamented with all kinds of jewelery and almost always appear next to luxurious items and accessories produced by some of the main Western fashion brands (Channel, Louis Vuitton, Hermes, etc.). These are somewhat ‘material girls’, striving to attain Nirvana, maybe in vain. In a way, these images both mimic and mock typical advertisement campaigns that one can find in glossy magazines. In one photograph, for instance, a girl in a meditation position stands on top of a Paul Smith perfume bottle. Another one portrays a girl being carried by two Chinese characters clutching Louis Vuitton bags and is obviously a parody of a Louis Vuitton advertisement. In one of the photographs, called “Fish have no fear for net” (which means that a disinterested fisherman’s net catches fish), the girl-fisherman is nevertheless sailing on a boat made of dollar bills. Another image, titled “Korean wave”, presents a girl standing on top of a risky stack of Samsung digital cameras overshadowed by the image of two famous Korean actors, and is an ironical take on the famous Korean film industry.... Humor and satire are essential to Lee’s projects and are manifested in many ways, but especially through the artist’s own persona, in what could be perceived or interpreted as a kind of self-mockery. Like Alfred Hitchcock, Lee continuously makes appearances in his works. Always wearing a black formal suit and sunglasses, he can pop up as a miniature in a small corner of a photograph or video, be found fishing silently or flying around his pictures with butterfly wings.

The butterfly, a being that goes through numerous transformations before it is finally able to ‘transcend’ and fly away is a recurring figure in his works, functioning very much like a metaphor. In a sense, through the invention of this character, Lee perpetuates his activity as an actor who is at the same time spectator of his own doings. The ‘burlesque’ and humor is an important artistic method that concerns the way authority, whether embodied in auratic objects or charismatic gestures, gets erected and deflated in one go. The word ‘burlesque’ was understood to mean stripping the conventions of their credibility or treating a serious subject ridiculously. Such scrambling of signifiers, symbols, and archetypes is pivotal to creating anarchy out of familiarity. Lee’s special comedy unmasks conventional signs of virtue and vice, recombines them and creates a new zone of stylistic freedom. A lesson in how frustrated expectations can, by sleight of hand, be transformed into comic relief?without the relief necessarily having to be reassuring. Lee Sang Hyun is fascinated by science fiction and the art of storytelling. He technically manipulates digitized old historical photographs by inserting and juxtaposing them with images from mass-media and internet games, creating artificial analogue paradises only to show us the surreality of reality we encounter in the technological globalised world. As part of an ongoing interest for this theme, the video piece The Painting of Hermit Riding on a Cow (2007), narrates a fantastic story, a kind of a fairy tale, where Lee features as a lonesome traveler. He takes us on a long trip where we find ourselves constantly shifting back and forth through different time and space zones. The first scene presents Lee in his usual black outfit with sunglasses roaming around a contemporary urban landscape with a metal detector in his hands, apparently looking for something important. We then quickly switch time zones as electronic minimal sounds inaugurate the scene where our hero Lee appears inside his yellow spaceship, in front of his control desk flying through numerous galaxies in a quest for a mysterious object. In outer space, he suddenly encounters a nymph (who strangely reminds us of the girls in Little Siddhartha), actually the guardian goddess of Andromeda, covered in jewels who sends the following message to Lee: “This is a bronze cow that was presented to Kim Hongdo of Chosun dynasty by Ong Kyebang, a Chinese merchant, a reward of Kim’s painting Seonin-ghiuh-do, a painting of a Hermit riding on a cow. It can be sold for 100 million dollars at Sotheby’s auction?find it under the wall of the Sea King’s Palace.” The next moment, Lee wakes up in contemporary Korea to realize that ‘it was just a dream’ but soon we are abruptly plunged into the past, revisiting the old historical site of the Joseon Dynasty with its mountains, valleys, and bamboo trees, as our hero is now well determined to find the bronze cow! And the journey goes on.

We find ourselves humming to the melody of ‘Lee in the Skies With Diamonds’ but once again, there is more than meets one’s eyes, for underneath these pleasant hedonistic paradises, there are graver undertones and a deep questioning of Korean society. Lee fuses comedy, journeys, music, and absurdity to provoke curiosity about social and political issues of our times. When Lee takes us to his country’s historical sites he suggests cross-cultural encounters and a link to contemporary times. His thorough investigations and meticulous research, suggest similarities between Joseon, where these old photographs were taken, and the social and political situation of contemporary Korea. The artist seems to build a parallel between the situation of centuries ago where foreign powers were competing for the Korean Peninsula and the one of Korea today?constantly under economic pressure from US and Chinese governments and North Korea’s nuclear power weapons. In a similar vein, Lee recently produced for his exhibition Empire and Joseon a series of four video vignettes which function very much like short music clips. Each video, made in 2008, is a single channel piece and their duration lasts the time of the soundtracks. Nostalgia, for instance, features a black-and-white photograph of a couple, a military man of the Japanese empire and a geisha from the beginning of the 20th century accompanied by a song interpreted by a famous Korean singer from the 1930’s who the artist used to listen to in his childhood. An ornamented coloured mirror, which has obviously been added to the original picture, slowly spills out peach-pink blossoms, that gradually fill up the screen until it is totally covered in pink and the original image is obscured. With Gabrielle d’Estree’s Nirvana, Lee revisits the famous controversial 16th century painting by an unknown artist entitled Gabrielle d’Estrees et une de ses soeurs and a mystery novel entitled Purple Line by Wolfram Fleischhauer. The painting displays Gabrielle d’Estrees (The mistress of the King Henri IV of France who had a mysterious death just before her wedding) sitting up nude in a bath holding (presumably) Henry's coronation ring, while her sister (In fact, who wasn’t Gabrielle’s sister even though she was described as her sister in the painting. Her real name was Henriette d’Entragues and she became a lover of the King Henri IV of France after the mysterious death of Gabrielle) sits nude besides her and pinches her right nipple. By technically manipulating the image, Lee renders life to the painting as the sister moves her hand up and down while taking the ring away from Gabrielle, a butterfly suddenly appears and starts flying around the screen, and Gabrielle also starts to move and this time touches her sister’s right nipple. The picture slowly fades away to reveal in the background, a bucolic image of a lake surrounded by mountains, while Gabrielle, who now appears with the face of a Buddha, and her sister remain in the forefront of the picture.

In Venus of Joseon, Lee uses Botticelli’s famous The Birth of Venus as a backdrop and replaces the original image of the girl with a black-and-white photograph of a legendary traditional Korean dancer. Choi Seung-hee, who was born in 1911, was praised as ‘Asia’s Isadora Duncan’ by Picasso and Cocteau and was described ‘to be at the peak of Oriental beauty and Zen.’ The soundtrack, called The Italian Garden, was performed by the dancer herself, and was known to be the first Korean popular song to be arranged in the Western style of ragtime. In the video, the dancer moves her hands up and down while one can perceive Lee from a distance in miniature, always dressed in his black suit and with his butterfly wings, flying around. Orient Express, shows the image of a post card, which was printed in 1921, the year when Mona Lisa’s painting from the Louvre was found after having been robbed. In it one can also see Lee with his fishing rod and butterfly wings, slowly coming in and out of the picture as the image of Mona Lisa slowly fades away to reveal the image of the statue of Nirvana, the Korean treasure from the 8th century, until both images come together to merge into a hybrid. By juxtaposing and confronting Eastern and Western icons, Lee makes the East meet the West and creates his own subjective view of a hybridized world. With Warhol and me and Sleep, instead of revisiting the distant historical or artistic past, Lee digs into the archives of contemporary art’s recent history and dares to approach one of its biggest icons, Andy Warhol. In a daring gesture, Lee mixes footage from the film Lies where he plays the main protagonist and segments from of the famous cult films directed by Paul Morrisey for the Andy Warhol Production to create a double-screen video installation he calls Warhol and me (2006). Heat, Trash, Women in Revolt and Flesh are known to represent and personify the spirit of the bohemian decadent underground scene which used to hang around Andy Warhol’s Factory. By confronting and juxtaposing supposedly ‘controversial and transgressive’ images but from two sides of the planet, Lee seems to question these films’ potential to provoke, undermining their emotional and visual impact. In order to produce Sleep (2006), Lee took one minute of footage from an anonymous film produced by Andy Warhol Productions and extended it to last the original duration of Warhol’s most legendary film. Lee presented this ‘fake’ Warhol film in a festival in Korea where he knew that most of the public had, of course, heard of the film, but never seen it. The most important part of this project was the public’s reactions when all of a sudden some realized that the film was a fake. Once again, Lee is here playing with questions of artifice and reality and how the power of the image is made through its media reception and recognition.

Though it is the case with any artistic tradition, we must say that the Asian tradition, especially the Korean, had heavily endowed art with spiritual meaning. All this had to change, as Korea became a modern nation through a long process of historical trials and errors. Lee seems to be an eccentric who, in a certain sense, is on a spiritual quest. Lee’s art form might be considered excessive for it connects to what is outside of what can be known and is sensed through exploratory forms of speculation and behavior. Lee tries to promote the radical alterity in which the potential of the unknown is acknowledged as a productive force. Through his hyper-cyber patchwork of images and stories, Lee, in his own way, revives and revisits this spiritual artistic tradition that constantly questions our histories, frustrations and desires.

Cristina Ricupero (Curator)

Double Narrative Perspective - emotional mapping of a detective investigating the futuristic past

Manu Park, Nam June Paik art center director