A Way to Live in a Vacant Lot

The ground under the feet is mushy. Buildings, trees, grass and people above it cannot maintain stability. This year, we have clearly observed the collapse of things we once believed to be constructed on firm foundations. And we realized that the solidarity of modern systems, including nations and society, is dissolving and transforming – in flux.

Witnessing the collapse and failure of the system that constantly produces ‘trash’ by reason of efficiency and rationality, artists, more than anyone else, sensitively read the symptoms and anxiety of a time and give them form. Artists today have a tendency to work under uncertainty, rather than working towards certainty. Particularly, forms of art such as installations, or community based art works that seek collaboration and solidarity, have diversified in contemporary art after the 90’s. Above all, what is prominent under these circumstances is that certain art forms, like installations or videos have received attention, in contrast to the relative decline of painting.

In the beginning of this essay, I am not trying to argue the death of an era of painting nor talk about the reason for its existence. However, it is necessary to start with a self-reflection on painting in the context of contemporary art, in order to critique An Gyungsu’s work. In other words, it is crucial to look at the inquiries and concerns coming in and out of the canvas by an artist who is aware of reality. What scenery can a painter imbue while corresponding to the changing of era, and go beyond the characteristic and the limitation of the medium of painting? In this essay, I would like to focus on the potentiality and vitality of the ‘vacant lot,’ and on the other hand, grasp the instability and the fluid symptom shown in contemporary art within the changing flow and aspects of An’s work.

Like Resembling What Is Seen

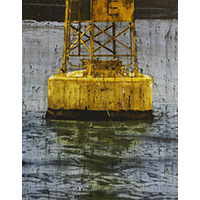

For the past couple of years, An Gyungsu has painted a middle zone, between construction sites and the natural landscape. Regardless of the gradual change in his perspective over time, An shows consistent interest in this ‘landscape of a middle zone’ that is derived from the contrast between nature and its surrounding artificial scenery or ‘surplus sites’ that deviate from the process of production and distribution.

In his solo show, 'Artificial Nature' in 2008, he exposed the vulgar taste of city dwellers in artificial objects of nature and in the crudeness of fake nature - through landscapes that depicted paradise, zoos, or fake waterfalls, in the front restaurants or fake caves, etc. Here, artificial forms are empty façades where people’s idealized desires are projected – they are exterior landscapes that imply the lack and excesses of today. Also, these city artifacts reveal a critical consciousness of the artist because they are regulated by social systems and create spatial order based on it.

In his solo show 'Barricade' in 2012, An’s conscious approach and attitude on landscape slightly changed. Moving his sphere of activity to Itaewon, An started to focus on the landscape where diverse ethnicities and classes coexisted. It showed the artist’s instinctive curiosity towards ‘uncertain things,’ such as people on the boundaries of the system. These interests were expressed through grass on the ruins of the construction site, some areas of buildings, or vacant lots, etc. Rather than the ‘social landscape’ of his previous works, An concentrated on the banal scenery of ‘vacant lots,’ easily seen in our surroundings. An creates existential connections with useless peripheral things or the residue of vacant lots, which he thinks resembles himself. The self-awareness of the artist relates to his situation of being located between the genres of art, as an artist whose major was oriental painting. Also it reminds us of the surplus attributes of art - that it is often regarded as useless in our social reality.

The artist is attached to the landscape in the way that he regards it as an object of experience, instead of locating it as an object of contemplation. This perspective starts from his looking at the ‘landscape’ as itself, which is no longer just an object for development from the capitalistic point of view, the artist’s own projection that reflects the fear of being abandoned, or just a subject matter for art that reveals his criticality. Removing strict intentionality from the editing process, the artist discovers a new methodology of “drawing what he sees” from his bodily experience. Here, “seeing” is not only a passive act that merely engages visual perception, but also an active act to understand and possess the object. This methodology is related to An’s habit of enjoying walks in his everyday life. The artist, who mostly walks a fair distance, becomes a flaneur and discovers hidden landscapes from all corners of the alley. Then he establishes a close relationship to what he sees, which allows him to become faithful to what he draws.

Instead of trying to strongly assert a certain message, An allows us contemplate our reality more realistically. This also means, when social issues and critical awareness become a question for himself, he flows this into his paintings. Therefore, these re-investigations of landscapes are not only a mere imitation of reality (landscape), but also an act of re-presentation, through An’s experiential exploration. The artist’s concerns are condensed in this flat and even painting. This reveals itself upon closer look.

A Place for ‘Ambiguous Things’

These days, artists’ ‘migrations’ affect their ways of sustaining themselves and provide important physical conditions for their art. For this reason, some artists use material or tools that are easily transportable, while others actively incorporate their nomadic condition as the main context for their work. Owing to unstable conditions and situations in recent years, An Gyungsu has constantly moved and stayed in different locations. However, these changes of scenery in his surroundings have deeply influenced his practice.

In moving his studio to the countryside of Ilsan, Gyeonggi province, there was another change in the landscape that the artist viewed and walked in. Unlike the city’s vacant lots in his previous works, An observes ‘the periphery’, the middle zone between (metropolitan) city and the satellite cities, from outside of the city. There is also a difference from his perspective, which is to include a wide field of view in a frame, instead of depicting magnified parts of objects or landscapes. If he captured the border zone of anonymous vacant lots in his previous works, his new work shows someone’s habitat that emulates a sense of private space. The familiar suburban landscapes that do not gain much attention, such as the spaces that substitute for the role of houses like a vinyl greenhouse storage, warehouse, and container, look somehow unstable because they implicate the possibility of development, in spite of the trace of humans.

An Gyungsu grabs things that we forget as quickly as the pace of the developments that erase certain contexts. Then he elaborately depicts them in his paintings as if he is promising not to forget their traces. The painting that is made through the techniques of scattering or the accumulation of scratched materials, ironically show the very flat texture of the plane. He also expresses the incompleteness and fluidity of the ‘flat vacant lot’ through the drippings on the surface. The traces of dripped paint, scattering, scratches or the sense of foreign objects tactically separate the viewer from the paintings. In this case, the dripping on the surface that cannot easily be separated can be seen as a ‘parergon’, dividing the inside and outside of the picture. Derrida redefines the concept of Kant’s ‘parergon’, which means a subsidiary part of the work, as the element that allows the work to go beyond the contrast between the content and form, or the boundary between the inside and outside of the canvas. If we apply this interpretation in An’s painting, a ‘drip’ is the borderline of painting and non-painting, where the work is generated through disrupting all the binaries. In this in-between space, main elements of the work coexist with its foreign or subsidiary parts rather inducing the aesthetic substance of beauty.

In his other recent piece, the artist makes the borderline image more concrete, then captures the very subtle moment into an image. Bright Night (2014) is a painting of an early evening landscape where darkness and brightness exist together. In this ‘in-between’ space, that is neither bright nor dark, the existence located in the border inevitably holds anxieties. But these anxieties are potentially mobile because they are constantly moving without pause. The other recent piece, which has the same title, shows both inside and outside of the landscape with a window in the middle. The reflected surface of the window that transmits both street life and the fluorescent light indoors, is a border-line where inside and outside overlap. The landscape recalls ‘faint things’ that can exist both outside and inside. In order to possibly contemplate these indistinguishable things, An tries to visualize the in-distinguishability as an image. That is, to locate ‘vague things’ for him.

Distant Landscape

We encounter a hectic development process in our everyday lives. The precarious landscapes caught between these developments create a space that is emotionally unstable. They are “unfinished landscapes” that refuse to be landscapes. These ‘non-spaces’ of the middle zone only offer a physical space and a functional condition for dwelling. It is closer to a temporary residence than a fixed abode. As ‘non-spaces,’ barren landscapes that deviate from development are, in other words, undigested remnants of capital and development’s desires. Then, what does the artist attempt to do and actually see, and what does the audience learn through the existing “unfinished landscapes?”

“Since pictures offer a proper point of view to the world, they are always connected to landscapes and interfere with each other (...) I always want my eyes to be looking at the world, to be constantly realistic, because artists must be capable of showing a certain attitude towards the world.”

- From the artist’s note

Moving beyond what narrative structure and pictorial expression can reveal, An Gyungsu explores the possibility of capturing certain ‘symptoms’ through his paintings, as he overcomes the inevitable physical restriction of painting. This means that regarding the problem of ‘seeing,’ the artist actively exposes his emotional changes that are generated when he encounters the world. The artist moves from gaps to borders, borders to vacant lots, “learning from landscapes.” He focuses on the potentials of the leftovers - the numerous vacant spaces of Korean society located between developments. The ‘fluid symptom’ retained in the objects, captured in his paintings is a metaphor for the conditions of our time and the blankness of Korean society.

The impossible spaces where development has ceased are retrievable because of their in-betweenness. The useless and pitiful features of things are the very reason of their potentiality. Walking straight into the landscape, the artist constantly makes brush strokes towards these possibilities. None of us in front of the drawing yet knows what we will encounter at the end of An’s journey.

Eunbi Jo (Chief Curator of Art Space Pool)

Thoughts on Certain Ruins

In waste products they recognize the face that the world of things turns directly and solely to them. In using these things they do not so much imitate the works of adults as bring together, in the artifact produced in play, materials of widely differing kinds in a new, intuitive relationship. Children thus produce their own small world of things within the greater one.

- Walter Benjamin, “Construction Site,” One-Way Street

Imperfect empty ground and imperfect ruins. In An Gyungsu’s paintings, ruins and empty grounds work as different names for ‘imperfectness,’ which means the landscape the artist takes as his subject of depiction are in the stage of the infinite ‘middle’ in between the start and end. It also means that the state of paintings the artist tries to achieve is directed towards a certain degree of imperfectness. An Gyungsu’s paintings take Bogwang-dong as their point of departure. The area is a place in which the artist took many walks when he had an exhibition at a space called ccuull pool in the winter of 2012. For him, the area is not a place for living but a place for ‘walking.’ There, he sees the coexistence of people migrated from other places, worn out objects that are closer to waste, old buildings, and construction sites as landscapes with another possibilities. He might have captured these complex and confusing scenes while taking walks, a practice where one’s body and gaze move together.

An Gyungsu brings the traces of time that has stood on empty grounds: different elements such as buildings along the street, construction sites, roadside trees, walls and floors in the interior of buildings. However, the actual sites that the artist has seen while he was walking become more and more omitted during the creation process of his paintings. In a more accurate sense, the artist omits the whole by depicting sections of buildings, ruins of construction sites, and walls and floors. Composed of arrangements of different parts, his paintings leave the perspective to see the whole as an imperfect attempt. In his works, fragmented landscapes are arranged in different places as pieces of a puzzle. Instead, the artist amplifies the accumulation of time and the imperfect atmosphere within such accumulation in terms of senses. There seems to be intentional ‘neglect’ in which the artist distances himself from the actual landscape that he has encountered. In this sense, one might argue: An Gyungsu’s practice maintains the warmth in his paintings by neglecting the objects depicted on canvases to a certain degree. In an undefinable atmosphere that is neither warm nor cold, the artist draws empty grounds, ruins, and newly developed lands to coexist in paintings.

An does not treat landscape as an object of representation and illusion; his paintings disturb viewers’ encounter with the sensibility of empty grounds or ruins. The white dots and dim marks of darkness in the interior of buildings are certain symptoms that artificial constructions give off right before they become obsolete, like a fossil. The landscape in the artist’s paintings lets viewers only sense the soggy air and humid temperature while concealing or avoiding the reality of the street. The situation of construction sites where the ruins of buildings and grass coexist thus becomes a sole landscape that is detached from the noise of the street and the effect of its surrounding order.

‘a bunker’ portrays a common parking space of a building. Composed of two pieces of paintings, the work presents an interesting composition that bears difference and similarity at the same time. The artist’s gaze does not enter the buildings and takes a view on the ‘crack’ of buildings that he has discovered while working along the street. He depicts them from outside: it is a landscape that is portrayed from the outside. The artist intuitively senses that there are uexpected things in the inside but does not bring them to outside. In ‘a bunker’, the artist surveys the landscape from the outside, from the red bricks and white walls to blue windows. The structures of parking lots which the artist represents in a similar composition bear difference in their textures yet share a common element: the existence of colors that run down both inside and outside of buildings. In the paintings, the colors are the only element that fills up the picture as if it was air that could go inside the landscape and move to any place. In ‘an empty lot’ series and ‘forest’, there are also colors that run down from the top to bottom, sometimes with less presence, other times overwhelming the landscape. To a certain degree, it might be possible to say that the running colors imitate the state of atmosphere such as rain or snow, which affects the mood of time and space: they are not an artificial addition; they exist as traces of neglected time, or as an element that amplifies the dampness of paintings. Then, what is the subject that has created a picture filled with a sense of dampness? It can be a painter, or it can be everyone that makes and sees roadside trees, sewerage, empty grounds and all the other objects. In An’s paintings, the place of empty grounds is passed onto the ruins of left-out wates, nails, and disposed objects. Among them, the scene in which grass grows through the construction fence reveals the hidden material of landscape that shows itself when one pays a close attention to it. Such material manifests as marks of green dot that can be left only by the artist’s brush stroke.

An’s paintings starts at Bogwang-dong, then disperses through other empty grounds. But isn’t also that an empty ground, meaning a place that is vacant, is actually impossible illusion? In the artist’s works, empty grounds are scattered around many places that are not far from us. Lightning with the interior lightings, stairway with stained and old stairway, and our flag with a construction fence in a rainbow rice cake pattern are different expressions of an ‘empty ground’ if compared to the artist’s other paintings. An leaves out many sections of a picture, depicting fragmented miniatures of a landscape. Through this, the place of an ordinary landscape raises the microscopic world embedded within it above the surface. The artist’s landscape of ‘the interior’ draws what was once a ‘background’ of other things in front of one’s eyes. However, the move is not dramatic nor spectacle. Rather, An’s paintings reveal his will to share his fluctuating ‘play’ of relations that he might have felt. a brick road, a painting depicting a pattern of paving blocs, is an example of such characteristics. In the work, the dense surface of paving blocs that are carved with omitted traces of time exists as an instant of a landscape that changes and moves itself.

The landscapes depicted by An Gyungsu take the leap among disparate materials rather indifferently. The question is that of the meaning of ‘becoming a landscape.’ Here, the notion of ‘becoming’ is a word that appears in the artist’s own writing. In his writing, An added a condition of ‘incomplete(ness)’ before the phrase of ‘becoming a landscape.’ In the paintings, the incomplete places themselves construct the time that becomes a landscape within them. Is he asking about how the unexpected and the common and trifling landscape coexist? The contrasting sensibilities, such as dirtiness in cleanness, uneasiness within tranquility, and sharp lighting within dampness, remain in silence as if they were traces and remain left after a storm of heterogeneous objects. The artist does not pursue landscape as a background that emphasizes something else but follow the scene of emptiness, which is ‘the whole’ as itself. Such emptiness is necessarily directed towards incompleteness. And this incompleteness might be certain anticipation for him not to give up watching, conveying, and rearranging the landscape of here and now. Moreover, it might be a promise for himself as a painter.

The landscape depicted by An Gyungsu has been constantly changing. He has gone through an artificial nature(solo exhibition, 2008) and a barricade(solo exhibition, 2012). Now, he performs his paintings in a perspective of ‘becoming a landscape.’ Frequently appearing in the works in the current exhibition, the walls and floors with minute cracks are traces of An’s thought on landscape: the artist excavates the repeated properties of landscape by depicting the streets he walked and the landscape he captures and is reminded of. As he paints the landscape with marks of time, An sees different conditions of landscape that are shaped by light and darkness changing in every hour.

Hyun, Si-won (Curator of Audio Visual Pavilion)

In Between Landscapes and Anti-Landscapes

After 2010, An Gyungsu's interest moved from social landscapes to the everyday landscapes. To analyze further, one can see the process of change; from a sensuous surface to the inner reality, from the satirical and metaphorical to the explicit and immediate, from the theatrical situation to the contemplative manner. His gaze and attitude has definitely changed from the past. There is no exact reason for this, however, looking at the changes in his work all the while, and having met with the artist several times, my opinion is that it may be a result of having battled desperately 'in order to survive as an artist' through his experiences in the system of the art society(external impulse) and his inner experiment of self(interal impulse) after throwing his empty plate in the world.

He hovers around the inner conflict he is faced with, that is, the boundary of in and out of paintings he is constantly given with, in setting-up the frame of what must be drawn. In September 2009, he looks at the landscape drawn on the barricades he encountered inadvertently in the street of Changcheon-dong, Seodaemun-gu and is shocked. There were multiplex houses on top of a hill, at the front, a blue tent covering the whole building, which was left half-demolished, and barricades for reconstruction, and a landscape of nature drawn on those barricades, and these three landscapes overlapped and came in sight of the artist.

To the artist, this out-of-the-blue and shocking landscape is no more than an everyday and general landscape of reality where redevelopment had long been forming. Activist or observative disposition, which had already been practicing methods of painting and photography, conceptual approach on the public, and etc with a critical eye on redevelopment or artificial gardens from 15 years back, may not be such much of a fresh form in contemporary art. However, the capitalist power exercise keeps repeating and the criticisms and reinterpretations on building natural environments as artefacts for consolation can but beget endless meanings.

Unlike such position viewed from within institutions, to the artist, the discovery of a new external landscape gave a fresh stimulation and the 'aesthetics of discovery' provides a new clue of creativity. This outset means that the internal impulse manifests first, before the external impulse, recognizing new perspectives through his vision. In other words, the images painted on barricades are not something new. After looking, thinking, painting, experimenting, colliding, conversing and writing texts about the world within his continuous topic, I had payed attention to the point which the artist developed his own autonomous language by making his cognitive thoughts flexible after repeating and circulating such actions.

Starting from the barricade landscape in Changcheon-dong, the 'in between landscapes(the middle landscapes)' are those that are painted on completed landscape architectures or barricades in parks, apartments, public lands and sites for redevelopment executions which can easily be seen in cities. Furthermore, the range of vision widens and even the traces which may be insignificant in residential ruins or street corners are drawn into aesthetic elements. With them, the artist masterminded the frames sensuously according to objects that he saw or had been shown, and expressed them in various forms of paintings from small sizes to large-scale paintings.

Their contents are also diverse. Looking at the objects, the artist rearranges the very small units of minute languages that lie dormant in his memory within his frame by telephathy-like instict. The overall nuance is gloomy, melancholy and deserted like a social orphan searching for an empty spot. This may be why they fit well with the ragged feeling of the rough space in ccuullpool. After finishing the paintings, the artist went searching for a specific place which they may be placed in and positioned them in the right place, the corridor and 4-5 rooms at the basement, which is going to be reconstructed.

They seem to be comfortable as if they were there from the beginning. The space, which has become useless, but is useful culturally and artistically, and therefore is more valuable, resembles the middle landscapes that can only be abandoned by the convenience of capitalism. There is doubt whether these spaces and lives, which can only live as marginal things like that of mayflies or time-limited lives, can ever regain their values in the whirlpool of rotating capital.

The history of the place created from the walls and space cannot be erased. As much as the layers of its time, the people, the memories, the traces or the illusions, and even the paintings that has embodied it, cannot be erased. Therefore, after the artist's 'landscapes' recreate landscapes disguised as nature, which is why they have to disappear, in their own frames(territory, area), wants to have their values recognized. It is because they are 'landscapes by landscapes'. It is the reason why landscape exists by anti-landscape, like the landscapes inside landscapes, and landscapes outside landscapes, even though they crisscross each other.

What was it that An Gyungsu was trying to find beyond the 'membrane'(the retinae of perception) covered with artificial landscape within the real landscape? Beyond the membrane, there is actually nothing. An empty landscape: it might exist as an empty landscape itself. To the artist, the landscape may approach the artist as an instinct of return of infinite landscapes. Could it be the attraction of impulse which we had when we were kids, playing around without concept making houses and breaking them using the deserted fake walls?

He is now moving towards a little more unusual place, leaving the 'barricade paintings' behind. He moves towards an empty lot. This place is a formless place where time and space can remain more than any other objects of paintings. Consequently, overlayed meanings are gradually disappearing. People fussing about in landscape places, then, reinterpreted meanings of landscapes are gone and only an empty space is left.

His next journey is unknown, however, at almost forty years of age, it seems that he has found out how he is going to use art by 'filling and emptying' and how he is going to fill his life's journey. The artist once said, “when I look at a landscape, I retrace the past, talk about the present and imagine the future." His general logic which has mastered the easy and clear solution through landscapes, touches on the meaning of may-be-abstract 'landscapes of landscapes'.

Kwan-Hoon Lee (Curator of Project Space SARUBIA)