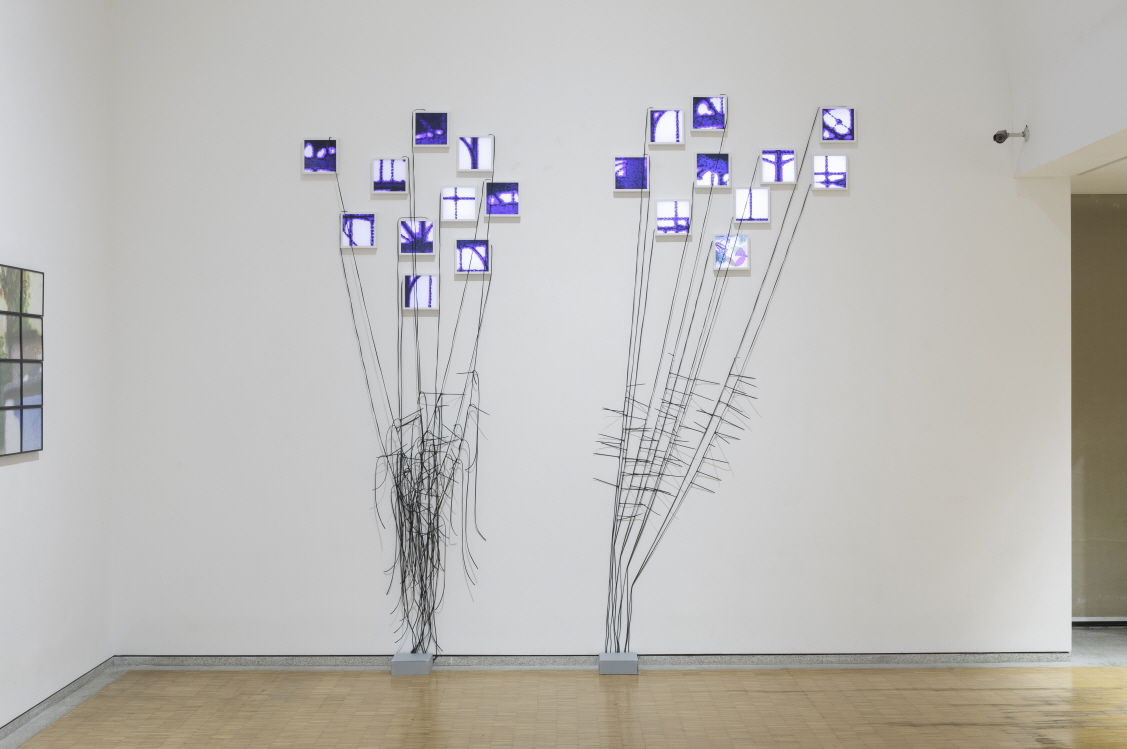

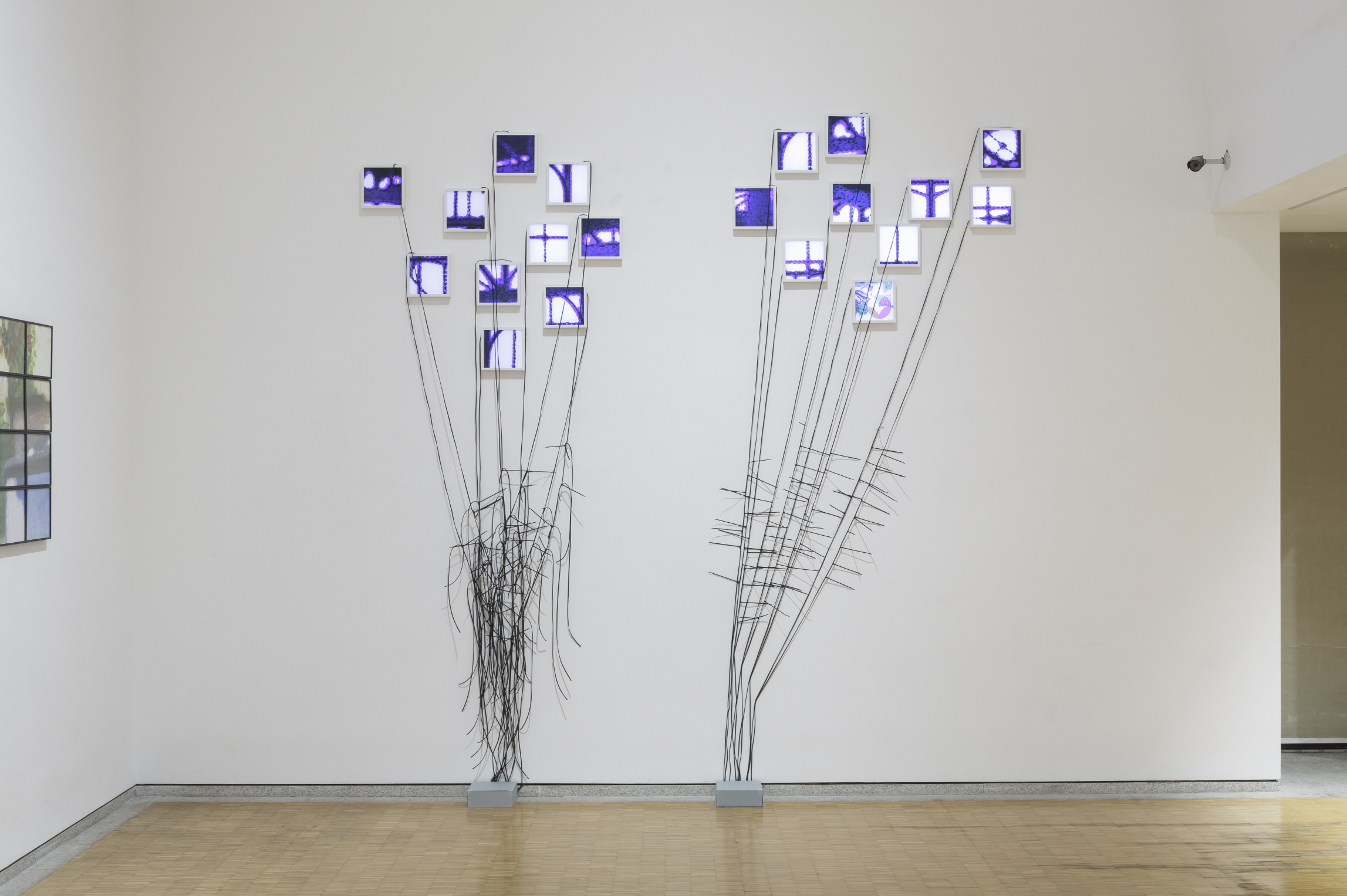

(L)Drawing pour 10 étoiles terrestres 3/09-15a, 2009-2015

Photo, Aquarelle, Photoshop, Facemount, LED, Cadres, Cable-tie, Dimention variable, 24 x 24(10EA)

Photo?graphics : Between Transparency and Opacity, the Movement Between Media in the Artwork of Yuyeung TCHINE

Tchine Yu-Yeung’s joyous and luminous art appears to me to be based on three main creative acts, each succeeding the other in a journey between the transparency and the opacity of the image, or, more exactly, a movement back and forth between photography and graphics.

The first foundational act is of ‘cutting out’, that is, the selection process involved in photography. The action of capturing, of recording a subject, is the starting point for most of Tchine’s works and gives them their theme. Whether this involves the interplay of branches standing out sharply against a background sky, the shadow of bars cast onto a bare wall, odd objects arranged on the ground in a garden, feet walking over rocks or simply standing still, facing the lens, reflections on the water’s surface, etc. In other words, ‘views’, selections, compositions, extracts that make the most of all the effects (framing, off-centring, trompe l’oeil) that this creative act allows. For example, the visual use of the ground-level viewpoint (eyelevel with the feet) as well as the vertical viewpoint (looking upwards into tree branches) undermines our sense of reality, offering us a perception that is somewhat out of the ordinary and rendering the transparency of the photographic viewpoint slightly more opaque. The (digital) photograph is then enlarged to formats often selected for their large size.

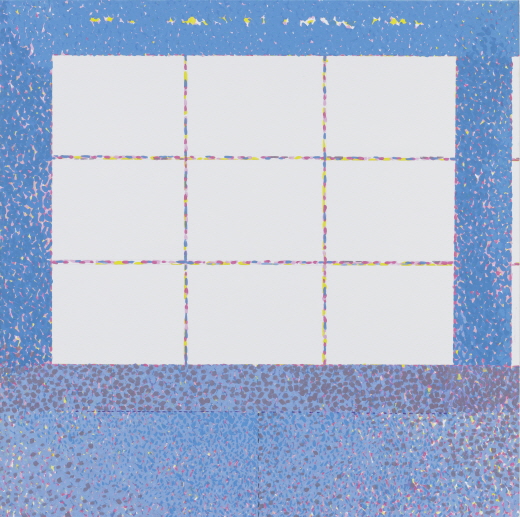

But the act of ‘cutting out’ does not stop at this simple first step (the photographic shot) ? far from it. Enlarging the image in fact in itself echoes this act by reproducing it, multiplying it, focusing on it, since the first image becomes in its turn the subject of the second: the photo is not ‘simply’ enlarged, but in the process also undergoes a transformation. It is systematically divided into smaller units, as if it had been passed through a grid template that physically breaks down the original photograph into a collection of smaller panels of equal size (‘tiles’), which are always proportional to the format of the whole enlarged image. The result has a strong visual impact, a mosaic effect, which already involves a back-and-forth game of perception between global and local, fragment and totality, deconstruction and reconstruction; the detail that is unreadable on its own and the cohesive unity (more or less) reconstituted. Between transparency and opacity.

Tchine Yu-Yeung employs a rather complex strategy to create this mosaic effect, as cutting each image into tiles offers an infinite number of possible combinations. The resulting collections of images are formally very different: sometimes (but quite rarely) complete, most often partial (like ancient mosaics, of which only fragments remain), in extremely variable spatial configurations. The pattern of tiles can be geometric, contain gaps, be set out in lines, consist of multiple shapes ? laddered, vertical, horizontal, etc. Each ‘installation’ offers in its way a different version of the same original image. It is the same principle as a musical variation, a literary variant or a linguistic declension: an infinitely reconstructable virtuality based on an original matrix.

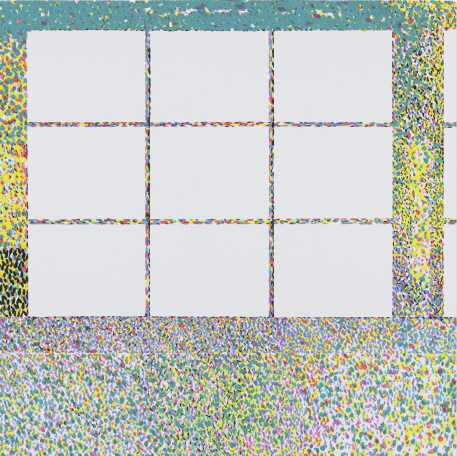

Finally, the logic of the act of ‘cutting out’ is also found (not always, but as often as possible) in how the works are displayed, the way they are hung in situ, particularly when shown in residential buildings, in public places or in specific sites. Tchine Yu-Yeung is very mindful of the space where her works are exhibited, and one of her most recurrent installation effects is that of the window: her mosaic-views are arranged on the wall ‘like’ windows (sometimes even latticed or barred, as in Prisons, which was displayed in a real prison during a show in Seoul). The tiled images are like openings looking out on the outside world. Rooms with a view. The display makes use of the architecture and the decor of the site, taking into account the floor, the walls, the ceiling, the columns, the (real) windows, the light, etc., considering scale and proportion, surface and depth, distance and proximity. This can have a potential trompe l’œil effect, if you like, but a relative one, as the ‘deception’ is often revealed by the work’s division into panels and, above all, its textures.

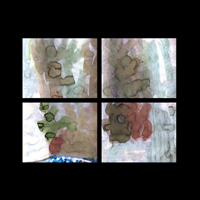

And so we come to the second fundamental creative act in Tchine Yu-Yeung’s art: that of transfer, of the captured image in transformation, the act of movement between media, which she pushes to the point of dizziness. This is the true heart of her creative universe: for example, in her series featuring branches (nicely entitled The Portrait of Painting: Flakes of Light). The process of making the work first involves, as we’ve seen, capturing the image as a digital photograph and cutting it into squares, as well as processing it in Photoshop, which makes the image particularly clear and bright (the blue of the sky becomes a dazzling white, as if it has been overexposed). This first stage results in a colour print on plain, ordinary paper. Next, this digital print becomes the subject of a process of ‘pictorial transfer’, as the artist uses brushes and watercolour ink (three base colours mixed in various ways) to rework the theme of the leaves and their infinitely varying shades of green. All the effects of colour, the luminescence of the greens, the transparency distinctive of watercolour, the superimposition of blots and strokes (not photographic blurriness, but ‘Watercolour Tachisme’) are combined in a superb and striking chromatic palette. After drying, the coloured surface is scanned again, and the digital version is reprinted on thicker matte paper and mounted. Digital print? Painting? Photo or graphic? They move from one to the other, shifting, superimposing, reinserting.

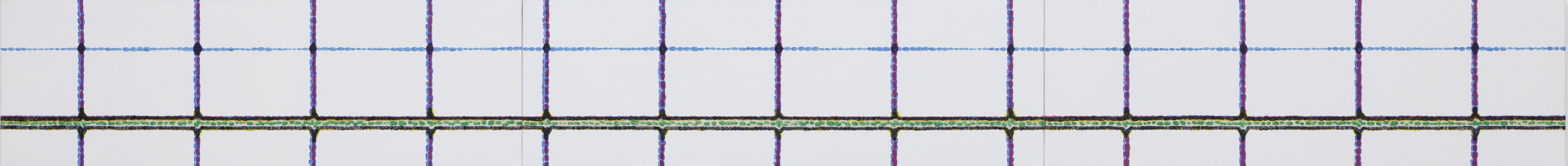

The same process is at work, for example, in the images in Prisons, except that instead of watercolour ink the work has pencil marks, small graphic markings made with three coloured pencils (magenta, cyan and yellow) ? which we can see very well when viewing the work close up to examine a detail in an isolated panel of the mosaic. Another difference is that the journeys, the crossings between digital photograph and graphic work, are this time repeated several times: after the pencilled drawings are printed, these are rescanned, then reprinted, then drawn on in pencil again, then rescanned, etc., in a sort of spiral exchange, a crazy circulation of transfers between different media that moves the work back and forth between photo and graphic, between digital and manual image, between material and immaterial, to the point where one loses one’s balance. To the initial creative act of separation (cutting out, division) is added that of recuperation (superimposition, multiplication): after the mosaic, the palimpsest.

The third creative act at the heart of Tchine Yu-Yeung’s artistic approach, and a direct extension of the previous, is physical and organic engagement ? investment in the opacity of the content through pure physical manipulation. This can be photographic, graphic or pictorial, as we have seen. It can also be sculptural or cinematographic. Two examples: One Way is a piece composed of both a wall-hung photo?graphic (following the principle described previously, starting from an initial photograph that is deconstructed then reconstructed in panels, printed digitally, reworked in watercolour, etc.), significantly enlarged (very large format), and a ‘sculptural’ element arranged on the floor. This takes the form of a strange spiralled object with the appearance of a sort of snake (or floor cloth) made from lead, which has been segmented into sections whose ends are covered in sheets of paper torn from a spiral notebook and painted in bluish watercolour. The sculpture is articulated in several pieces. A trompe-l’oeil effect results: seen from afar, the object seems to be a pipe of creased lead, heavy, solid and massive, but seen up close ? and above all, when touched ? it proves to be very light and soft: a simple wrinkled cloth, painted in the colour of lead, which has been sewn together and stuffed with light padding. Observing further, we discover that the enigmatic object, massively enlarged, figures in the wall photo?graphic: the images are none other than the same spiralled object photographed in close-up at floor level and then visually transformed by strokes in watercolour, making use of all the pointillist and luminous reflections possible in painting. In this way, the sculptural aspect of the object slips between photo and graphic in a movement between media, transfers that characterize the work of Tchine Yu-Yeung.

One last example: the work Via Zero. It also features two elements, and it introduces a cinematographic aspect. On the wall, we see lines of small white clip-frame squares, most with a circular shape in the centre. There are around 50 in total. As we get closer, we can make out from the relief and the colour that each is in fact a CD sewn onto crumpled white cloth that enwraps it completely, like a shroud. On this immaculate cloth backdrop, small splashes of bright colour increase progressively: one splash on the first square, two on the second, three on the third, and so on up to nine, then nothing on the tenth, and then starting over again (one on the eleventh, etc.) When we come to the end of these lines, on the wall at a right angle with the work we discover a new and final image: a video projection showing an animation of the cinematographic capture (in continuous motion) of the series of coloured dabs of paint that we have just viewed filing along the wall. The animated film is an ordered and rhythmic optical treatment of the coloured paint marks (1, 2, 3, etc.), which, distributed spatially in the division of the white squares in the wall work, are now found temporally recomposed by the animated projection. The film has sound (the CDs enshrouded in their white screens are silent), reproducing a pulsating rhythm, a sort of beating. We have gone from photo?graphic to cinematic?sculpture (with sound). Such are the back-and-forth movements, the transfers, the shifts and transitions between media in Tchine Yu-Yeung’s jubilant art.

Philippe Dubois (Art Critic, Vice-president of University of Paris III)

more

Between Images

Guest artist at the Korean Cultural Centre in Paris in 2007, Tchine Yuyeung has lived and worked in France since 1969. Today her art is shown all over the world. Her works are characterised by strong interactions between painting, photography, digital imagery and installation. In this way, the perceptions of ‘human’ and ‘machine’ are superimposed. This lies behind the choice of organising the exhibition around the theme ‘Between images’, representing the idea that her work operates between artistic media. The concept of ‘Between images’ rests on two different phenomena: art as a process and the notion of specific place.

Tchine’s work is dynamic in the sense that it is intrinsically a process that involves the interaction of hybrid media. Photographs of a subject are interpreted in paint and reworked in digital format in a back-and-forth process between photography and painting, a process that introduces the idea of the infinite in the work, giving an impression of the opening of a space in which the work can continue to unfurl freely, in all its potentialities. This superimposition of various texture types (a handmade image reworked with a machine) creates the effect of watercolour, which highlights this sense of lightness and liberty.

This unfurling also manifests itself in the relationship between the artwork and its location, in an approach that falls within ‘site-specific art’. The site where the work is exhibited and the site’s history are integrated as ‘pre-traces’ in the dynamic creation of the piece itself, in the process of deconstructing and reconstructing the work, which is shown in relation to the place where it is displayed. All of the aspects of the artist’s work (fragmentation, framing or off-centring of the subject, the installation, which varies from one space to another) work together to create a new representation at each showing, the site in symbiosis with the artwork, which takes on different aspects in each new configuration.

The two new works presented in this exhibition, Via zero and The Portrait de la peinture, are symbols of opening out. The Portrait de la peinture is a large window that offers us a view of a landscape, as well as the media used to produce it, a mix of painting and photography in an adjustable artwork (its dimensions can change according to the exhibition) in the style of a film frame. Via zero, which incorporates DVDs (a modern medium for images) camouflaged against unbleached cloth (a reference to monochrome), which itself is a sort of quilt with stitched forms (producing a painting effect), suggests the movement of the rotation of the hands of a clock. According to the artist, this work represents her entire history, as well as a return to point zero: a fresh start, a new opening.

Sou Hyeun KIM (Curator)

more