Hyungmin MOON : Challenging Orthodoxy and Ceaselessly Questioning Life

Those who do not know about Moon Hyungmin mistake him for an artist who deals with social issues or criticizes consumerism. I was one of them as well, until I met him. I assumed that Moon's kitsch sculpture General MacArthur and the melting Mickey Mouse made of sugar and beeswax from the series Love me two times were derisive cynicism of the pro-American rightists in Korea, the ambition of American imperialism, and the consumerism that is so pervasive in the US. Some critics believe that Moon's works such as Unknown city, Unknown stories and Lost in supermarket represent the aesthetics of 'erasing.' They say that Moon intends to explore the monstrous aspect of capitalism carried by unified symbols and exchange values through his works of erasing, erasing the memories of a city in Unknown city, erasing traces of sociality, re-layout and dissembling newspaper articles in Unknown stories, and erasing the names of symbols that jam pack the shelves of a supermarket in Lost in supermarket. Against our expectations, Moon Hyungmin shakes his head in disapproval at such serious interpretations of his works, including my own.

Questions incessantly posed to the audience

Moon Hyungmin is not interested in either criticizing society or participatory art. Moon feels ill at ease with art that seeks to be instructive about right and wrong, to guide the viewers in a certain direction by showing something persuasive, or to evoke the viewers’ emotions. As an artist, Moon Hyungmin resists defining things in a fixed frame. He keeps distance from the logic of right and wrong and critical thinking, and 'anti-artistic' sentiment against serious and cliched art. He simply taps comic and parodiable situations and asks always the audience, 'Well, this seems unusual to me. What do you think?'

Questions incessantly posed to the audience

Moon Hyungmin is not interested in either criticizing society or participatory art. Moon feels ill at ease with art that seeks to be instructive about right and wrong, to guide the viewers in a certain direction by showing something persuasive, or to evoke the viewers’ emotions. As an artist, Moon Hyungmin resists defining things in a fixed frame. He keeps distance from the logic of right and wrong and critical thinking, and 'anti-artistic' sentiment against serious and cliched art. He simply taps comic and parodiable situations and asks always the audience, 'Well, this seems unusual to me. What do you think?'

For example, to my surprise, the beeswax Mickey Mouse or General MacArthur made of icing sugar are absolutely nonpolitical. The sculptures of Mickey Mouse carrying the atomic bomb appearing in the top animated series the Simpsons family and others are not symbols of American imperialism. The double standard of the Americans about war in their everyday lives is expressed by the beeswax Disney character melting away. As a joke about blind idolization of General MacArthur by Korean people, Moon made his sculpture out of icing sugar so that it would be ravaged by ants. Out of curiosity about people who are fascinated by the illusion of ideology, Moon merely reveals one aspect of it. And that's all there is to his art. No more, no less.

More than anything else, Moon Hyungmin does not believe that artists have their own distinct ethical code or auteurism. He rarely believes that art is such an exalted, lofty thing that so many people make it out to be, and this attitude is projected directly onto his works. A good example is The Virtue of Behavior: 45kg. This title was nothing but a note Moon left for himself but does not remember what it was about at all. By leaving a clue to a memo which the artist himself does not discern as an artwork, Moon emphasizes that no clue or answer can be a solution and creates a situation that is impossible to interpret. He goes one step further: by shining a light onto a colored canvas, he dazzles the viewers, making them feel reluctant to look up at his painting. The Virtue of Behavior: 45kg, urges viewers to not take art too seriously and not read too much meaning into it.

Likewise, the 9 Objects series expresses the thoroughly diluted intention of the artist for creation and decolorized color of the artist's individuality. Some may offer quite inadequate interpretations of Moon's 9 Objects as criticism of the acquisitive, otaku (maniac) consumerism of modern society. To produce the 9 Objects series, Moon photographed various objects that were collected and cherished by someone from the same angle and made them all the same size, and then printed them out by an automatic digital printer. Moon tries to remove the individual style or character unique to each object as completely as possible. He even eliminated their shadows and put them all against the same background color, and he arranged them in a rectangular formation. He did not give any of these photos a frame because he wanted to eliminate emotion and show each object as it really is. This is Moon’s way of existence as an artist.

A Sense of Humor and Comedy in Everyday Life

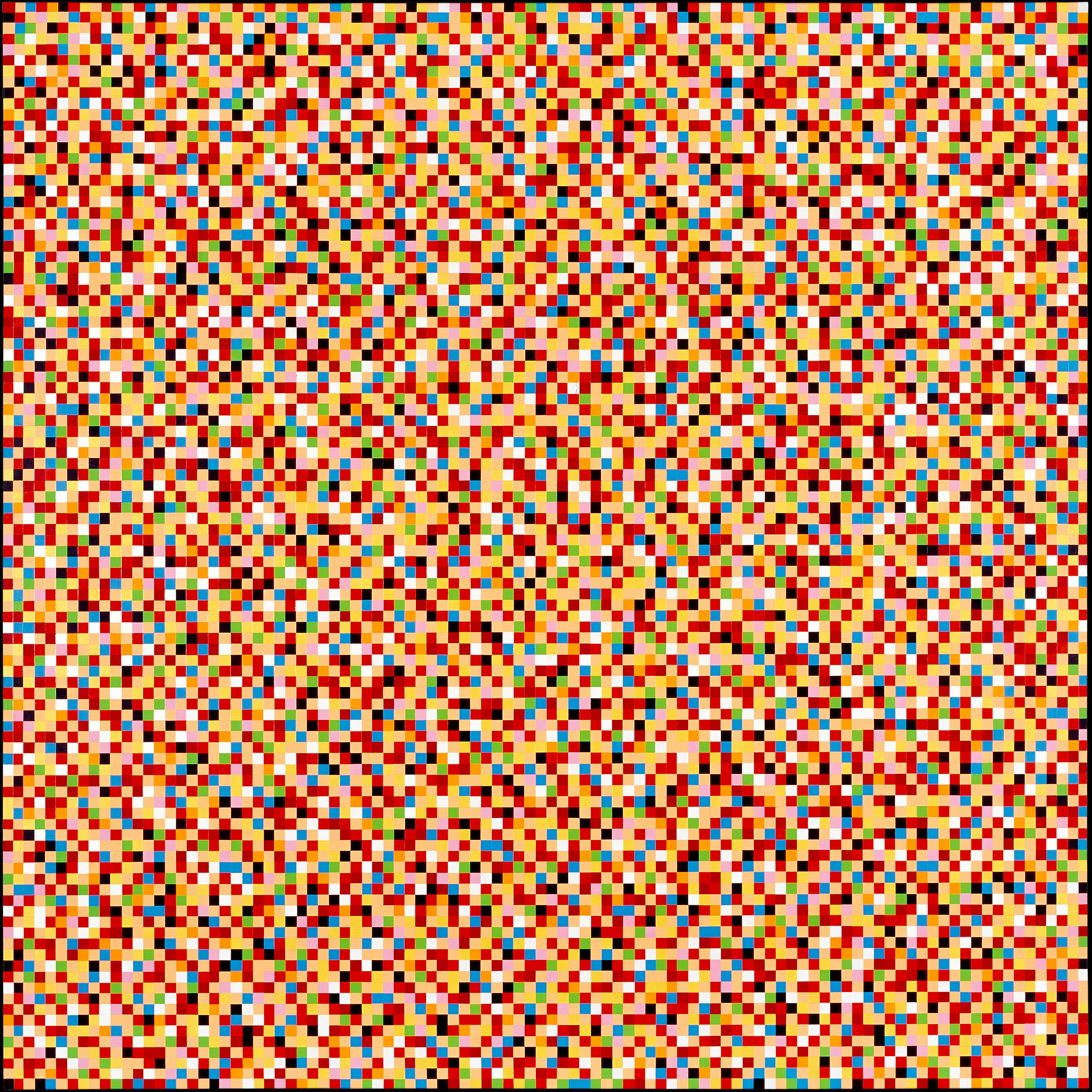

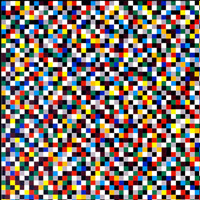

As a child, he was lucky enough to have the opportunity to use the Apple II and Mac Classic computers, which should be recorded as legends of computer history. That may be one reason why he is comfortable with the computer as he grows old working on photography, design, animation, and video work rather than conventional forms of art. Through the By Numbers series, Moon reveals the sensitivity of thoroughly and exquisitely calculated computer culture. Using the computer, he analyzes the 10 most common words in magazines, and he assigns each word a unique color in the order of the most mentioned word with the most used color. He then uses these color-word combinations to produce amazingly precise grids. Moon produces a grid pattern similar to that of Professor Lev Manovich, author of Language of the New Media, who made visualized statistics of a massive volume of images according to chroma and brightness. Moon originally planned to produce a video work using a display with one hundred LCD panels on which the color field constantly changes according to data entered. However, cost considerations led him to do a series of paintings instead. He shows the viewers colors and patterns that are changing according to the story of specific social issues through the By Numbers series painting.

Moon spends quite a lot of time in calculation and preparation for work not to mention actual work. He conducts research, reads books, makes important indexes for color work, and sorts out and accumulates diverse images and ideas for his work. The form of artwork itself is understated and impeccably shaped and densely covered. On the other hand, inside his work are hidden multiple layers of code that would provoke light-hearted thought and the occasional bitter smile. For example, he parodies the titles of American pop songs and uses them as titles of his works, the intention of which is very interesting. His work I love you more than you'll know is the title of a song by Blood, Sweat and Tears, an American music group. Contrary to its affectionate title, I love you more than you'll know depicts dense scenes of Korean lawmakers tangling and fighting endlessly. This piece too was originally planned as an animation to show the scenes of lawmakers exchanging blows in slow motion, but it ended up as a painting. Moon's recycling project with the long title A doghouse built out of my own artworks damaged due to storage and sales problems after costing $3,000.00 for production and $6,000.00 for shipping for a one-time exhibition in London, likewise makes viewers smile bitterly. Looking at a doghouse, viewers cannot help but laugh and naturally come to witness the irrational reality of art creation.

Another good example of satire is 道不拾遺記念, 1989 Do-Bul-Seup-Yu, a variation of a badge that Moon found at the market in China, was originally produced in commemoration of the Korean War with the face of Mao Tse-tung as he looked in 1951. In Moon’s version, the face of Mao is replaced by Eom Jeong-hwa, a famous Korean singer, and the year of her debut, 1989, the same year that when a Korean version of Karl Marx’s Das Capital was published, is inscribed at the bottom. But, today no one even remembers the loss of ideology. Moon asks us 'Don't you think there is something wrong with this situation?' While making a bitter smile at the look of Eom Jeong-hwa inscribed on the familiar totalitarian propaganda badge, we become melancholy when suddenly asked such a serious question by the artist.

Another good example of satire is 道不拾遺記念, 1989 Do-Bul-Seup-Yu, a variation of a badge that Moon found at the market in China, was originally produced in commemoration of the Korean War with the face of Mao Tse-tung as he looked in 1951. In Moon’s version, the face of Mao is replaced by Eom Jeong-hwa, a famous Korean singer, and the year of her debut, 1989, the same year that when a Korean version of Karl Marx’s Das Capital was published, is inscribed at the bottom. But, today no one even remembers the loss of ideology. Moon asks us 'Don't you think there is something wrong with this situation?' While making a bitter smile at the look of Eom Jeong-hwa inscribed on the familiar totalitarian propaganda badge, we become melancholy when suddenly asked such a serious question by the artist.

As can be seen thus far, Moon is very interested in collecting, gathering, transforming, and composing images to create something. Moon is very talented in collage aesthetics, which recomposes images through transformation and editing, and applies to creation of new artworks by adding or drawing. By 'hollowing' visual images of a city, everyday symbols, and products, Moon recomposes them anew. In Unknown city, Unknown stories and Lost in supermarket, Moon tells stories about our times, in which similar symbols are produced all around the world. Although differences in languages seem impossible for us to comprehend like insurmountable walls, under the surface are similar symbols, scenery, and spectacles wherever we go throughout the world. Based on minimalism, Moon simplifies the order of symbols such as buildings, people, advertisements, the sky, automobiles, display racks, and incidents which exist everywhere in his own way and recomposes images. Of course, he poses a question 'that has no answer' about what is the dominant logic behind such images and how the viewers would think of them. It is up to individual viewers to make decisions.

For Moon Hyungmin, our ordinary life is extremely social. Instead of forcing empathy and imposing a specific ethical code on viewers, Moon asks a question about this comic world to himself and the audience. In the driest manner without auteurism, Moon ceaselessly asks us how we need to comprehend meanings of the symbols prevalent around us. And he enjoys revealing multi-layered situations with layers of blind faith, misreading, difficulty in communication, and impossible comprehension, which hinder us from understanding the reality. Of course, he does not demand understanding of the audience. All he does is show cryptic locations of reality in a humorous and comic way without being serious. Then, we feel as if something were missing. We wonder if the essence of the situation will become clear at all when questions about this cryptic reality are repeatedly posed. Is it too much for me to expect such situations under which more aggressive communication, solidarity, criticism, and possible comprehension are found in his works, which do not end with a self-contained smirk?

Kwang-Suk LEE (Professor of Seoul National University of Science and Technology)

more