Bong Chae SON, Mudeung Museum of Contemporary Art

Birth

1967, Gwangju

Genre

Painting, Installation

Homepage

Migration: Portraits of People Today

I.

Bong Chae Son was invited to the 2nd Gwangju Biennale with his installation work titled, Invisible Sight and ascended to instant stardom at age thirty. The 207 bicycles that hung upside down from the gallery ceiling caught the viewer’s attention with their squeaky sound effects and impressively synchronized motion. Son’s kinetic art was written up not only by the domestic press but also by the world’s leading media such as CNN, BBC, and NHK. Although his installation had triggered an explosion of public interest and raves from critics, he could not continue his large scale productions because of financial difficulties. Although he struggled to complete the work, there was no one who could sponsor the project. A curator from the LA Contemporary Art Museum who came to see the Biennale offered him an international exhibition if Son could ship his work to the museum, but he did not have the financial resources to transport his work, so the offer never materialized. This has remained a painful memory to the artist.

Opportunities do not come around often for anybody, but it is especially tougher for artists. If there was someone who could have sponsored him, Son would have become an internationally renowned artist by now. One episode that I clearly remember happened at the gallery in the Shinsegae Department Store in Gwangju about a year after the Biennale. In the exhibition at the Gallery Shinsegae, Son placed a pig inside the exhibition space for a performance, and the unpleasant smell of the pig’s excrement was in violation of the department store’s regulations, so the artist had to get rid of the pig. This pig performance incident became one of the episodes that reveal Bong Chae Son as a true avant-grade artist in spirit.

II.

Ever since, I have remained interested in the artist’s work and even wrote reviews of his work for the monthly Wolgan Misul magazine. However, it became increasingly difficult to hear news about his work and there were rumors circulating that he was operating a street kiosk in downtown Gwangju. I was startled and yet curious, but it was just very hard to reach him.

“At that time, Kinetic art was new, but such a large scale work, as is today, has slight chance to enter a collection. But I didn’t care about reality and just concentrated on making the work. As a result, I was left with a debt of tens of million won, so I had to go through a lot in order to clear that debt. There was nothing I didn’t do to pay back my debt, from odd jobs in construction and shipyards to pulling a street vendor cart”, says Son. Indeed, the consequences from the making of Invisible Sight, which was installed in the exhibition titled, Authority section of the Biennale made him stronger in the end. Enduring financial struggle and soul searching for several years, Son began making three-dimensional paintings from around 2000. His work from the 1990s mostly contain satire of authority and social critique. Starting from the 2nd Gwangju Biennale in 1997, he was continuously invited to the following Biennales in 2004, 2006 and 2010. And the sequels to the Invisible Sight, such as, There is No More Dinosaurs, Who is Next?, Where Are You Going? were enough to grant him recognition as a major artist. Boundary-Substance Is Not Seen was produced around this time and became the first of his 3D paintings. Introduced at the Gwangju Biennale in 2006 for the first time, this massive installation work used images of the Jeollanamdo Provincial Office building, which is the historical site and living witness of the city’s modern history. He segmented the images into several sections and displayed them so viewers can see the work while walking through the sections. His ‘Boundary’ series continued for some time.

III.

Around the time he was working on the ‘Boundary’ series, the artist was trekking across the southern region of Korea in search of historical sites, when a particular sight caught the artist’s attention. It was an uprooted tree hauled unto a large truck, on its way to be sold off, and this sight somehow alerted the artist. “At that moment, I felt a sudden hollowness in my heart. So many landscaping trees in cities are, as a matter of fact, being uprooted and sold to decorate street corners. I then remembered New York since it is a site where different ethnic groups gather from around the world to fulfill their dreams. If they had a good life in their homeland, why would they have moved so far away? Moreover, most immigrants are actually placed in the bottom of society,” says the artist.

Son’s empathy for the landscaping trees stems from his youth years in New York. He had dreamt of becoming a cook when he was young, but his professor Hyun Joong Shin strongly urged him to go to New York and study, which he eventually did. The four year experience as a foreigner in New York was the source of the artist’s emotional reaction to the uprooted trees. Even after he came back from New York, his was the life of a wanderer, an uprooted person.

Bong Chae Son’s

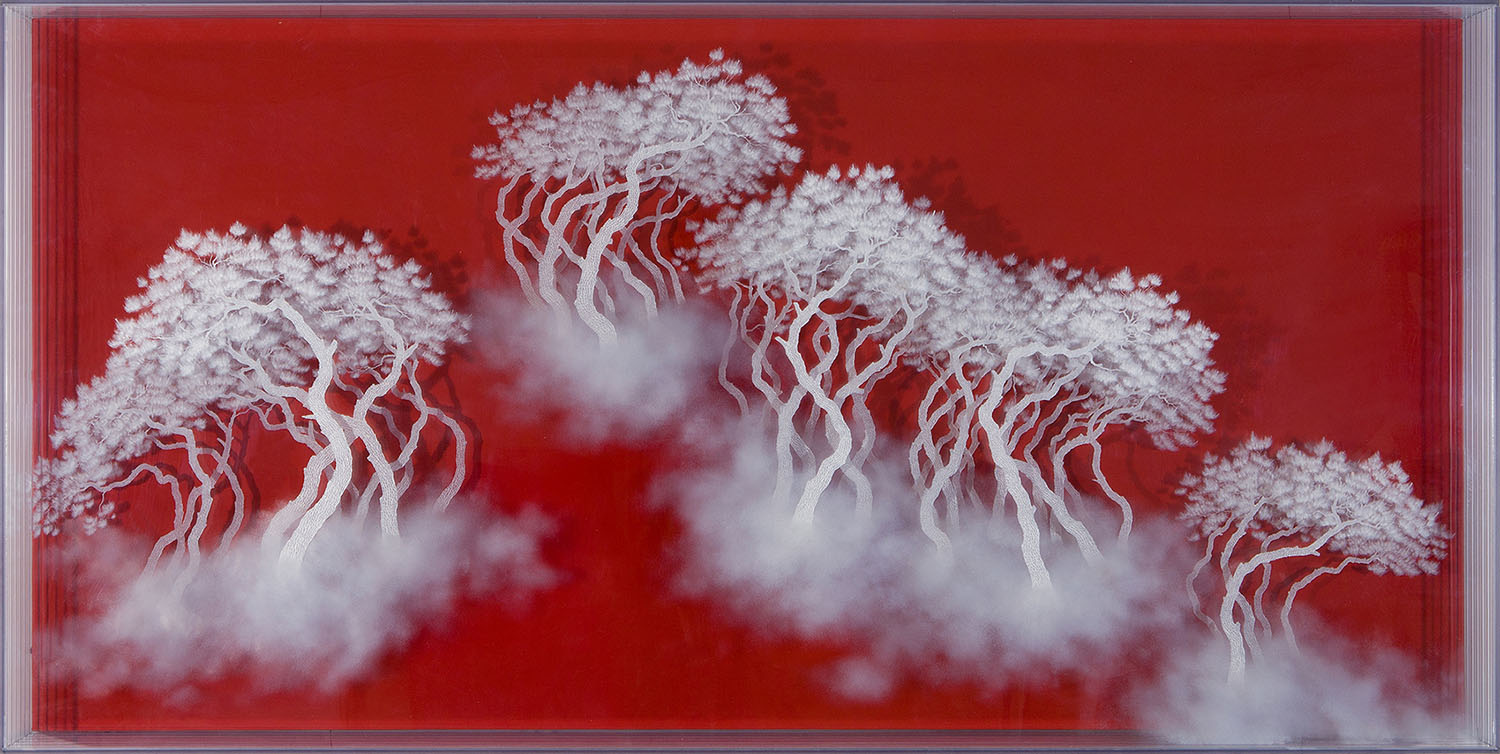

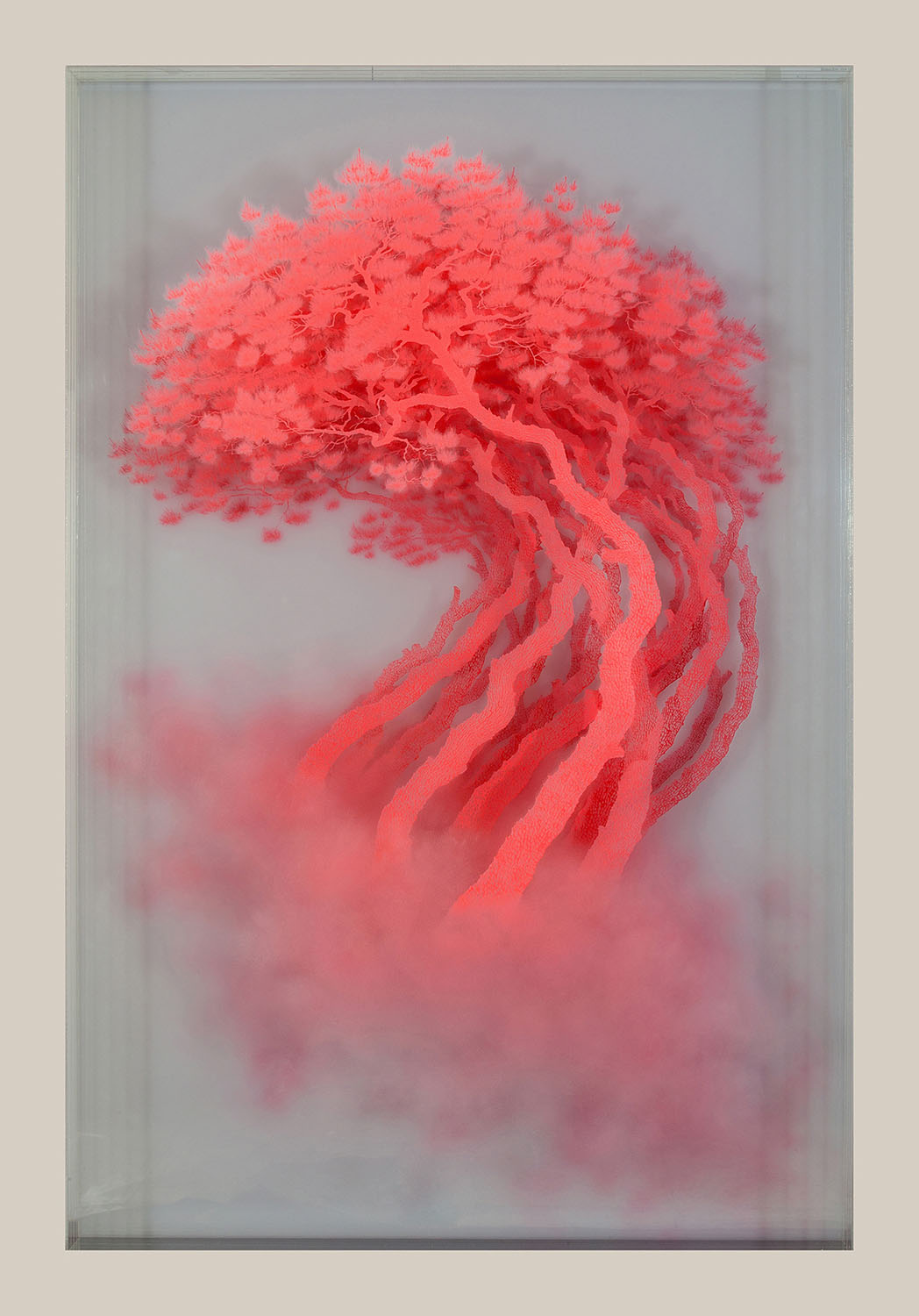

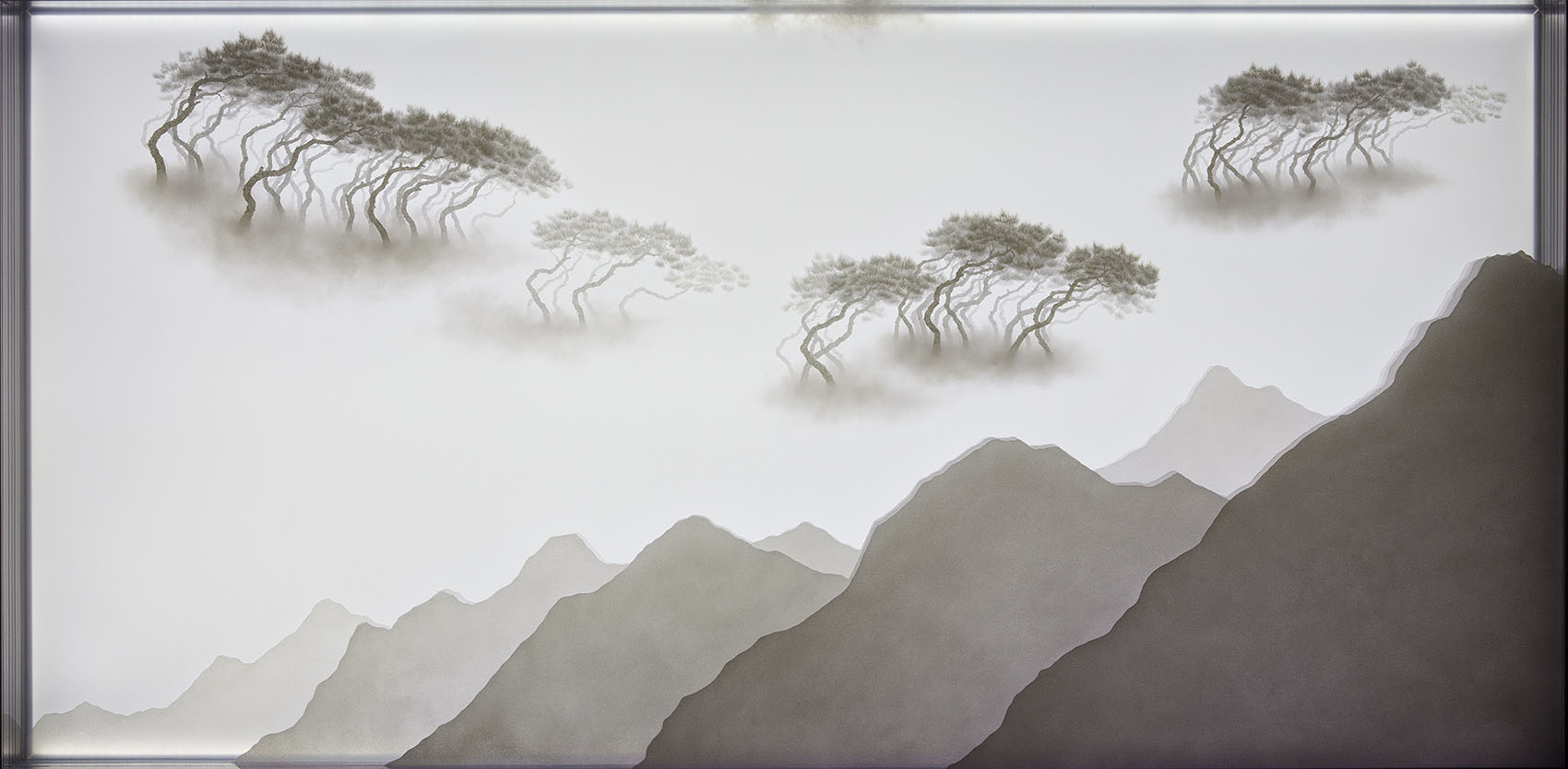

We can find the foundations for migration theme in the earlier editions of his ‘Migration; series. In the paintings of the uprooted trees standing on clouds, or the shadows of the lakeside tree, the names of migrants are written in English: there is a tree standing on clouds and through the clouds, there is the White House and under the White House, endless horizons of the ocean is represented with the names of migrants written on the surface of the waves. It is difficult to find another work that embodies the meaning of the ‘Migration’ with more clarity. In other words, the more recent ‘Migration’ series have purged the names of migrants and by erasing the names, the artist explores means to convey the subject matter in a more connotative and abstract manner, and to indirectly suggest through aesthetic experiencing its meaning to viewers. The appreciation of the work is thus left open ended. Whether the viewers interpret it as modernist landscape painting or identify the predicament of migration, everything is up to the viewer’s choice of reading and aesthetic perception. The important fact is that Bong Chae Son’s 3D paintings create opportunities to experience a new and experimental aesthetic within the conventions of existing landscape paintings. But can we still call it a landscape painting?

Maybe we should begin anew by reinterpreting the meaning of the ‘Migration’ series. All the trees that he paints are uprooted. It is very symbolic that the artist represents these uprooted trees on top of the clouds, detached from the earth bed--its origin and its home. The trees in his paintings do not reveal their roots in the paintings, but are mostly hidden in clouds that always move without definite objective which is very different from the trees in traditional landscape paintings that are represented firmly on ground. As we all know, clouds or fogs do not have any foundations and so the artist’s representation of the tree roots on the clouds is imaginary. They are foundation-less, uprooted, signifying migrants who wander around and cannot settle. If his trees symbolize migration, nomads or urbanites who wander aimlessly as a result of urban developments in an age of industrialization, then an extended, more comprehensive interpretation becomes quite substantial.

Jin Sup YUN (Art Critic, Prof. of Honam Univ.)

When Attitude Becomes History

Today’s definition of contemporary art has expanded to include a near-infinitude of forms and languages. Not only concepts, traditionally considered an initial phase of the making of art, but thoughts, attitudes, spatial interpretations, and even physical movements have undeniably also been included into the ranks of art. It has become impossible to explain aesthetic concept or form without mention of the other. In other words, formalism long insisted on the aesthetic language of an artwork being discerned and assessed exclusively through its form, but has suddenly been thrown into retreat or even made irrelevant. Spectators have become somewhat desensitized to the strangest of artistic creations and have ceased wondering whether such things are truly works of art. They are now prepared to be pleasantly surprised.

One example of this change is the 1993 Venice Biennale where, under the theme The Cardinal Points of Art, a variety of forms of avant-garde experimentation were introduced. Aperto, a recently-opened section spotlighting experimental works from young artists, offered a glimpse into the future. One Aperto artist was Rirkrit Tiravanija, a Thai-American who installed a piece in the form of a gondola, the iconic Venetian boat.

However, his was not a wooden gondola constructed for tourists to travel the civic lagoon. It was a metallic work of art berthed inside an exhibition hall and intended for spectators to experience in an entirely unique way. Prepared in the gondola were a gas tank that kept water at a boil and boxes of instant cup noodles for anyone to eat onboard. For the spectators who came to the Biennale, this unexpected chance to slurp noodles on an artwork must have been a pleasurable and fortunate surprise. The noodles were, of course, free of charge.

From the perspective of the contemporary art world, where spectator participation is an ever-increasing presence, this type of work is not particularly unusual. But sixteen years ago, it generated considerable controversy over whether it might be a sculpture, an installation, a mere performance or an example of social activism. Some even argued that it was a Venetian-style welcoming event disguised as a work of art.

This blending of viewer participation and performance as an art form that began with the Fluxus happenings has become commonplace over the preceding twenty-odd years. In other words, attitude and concept have merged into a single aesthetic form, triggering controversy over its nature?whether it is visual or physical art?and eventually matured into a more complex form of art. That the contemporary art of today is not limited to static objects hanging on a wall, but is rather a moving, speaking, inter-textual medium that invites participation from spectators is highly significant in terms of the changing social role or function of art.

The works of artist Son Bong-chae are also somehow part sculpture, part installation, part performance, and complex; yet they are also heavily dependent on the direct and indirect participation of spectators. In other words, his art is incomplete without the crucial component of spectator participation. But rather than leading spectators to participate through action, his work is completed only when a spectator’s participatory curiosity achieves satisfaction through a narrative journey on the stepping stones of consciousness laid by the artist. This is due to the aesthetic stories he wishes to discuss being in most cases social and historical and themselves the large and small realities that surround life. It is also because the materials that constitute these stones are intensely honest as well as loaded with similes.

The label attached to Son Bong-chae’s art is made obvious in the materials he selects for his art. Until now, his aesthetic tools have consisted of two materials. One is bicycles; the other is panel paintings, images drawn on layers of polycarbonate and then superimposed. This is why he has become better known as ‘the bicycle artist’ than as ‘the artist Son Bong-chae.’ Regardless of whether labeling art may be good or bad, Son Bong-chae now bears this label. In other words, he has joined the ranks of those other artists who are identified by their subject matter, such as the well-known painters ‘of water drops,’ ‘of barley fields,’ ‘of horses,’ ‘of rape flowers.’ Considering the numerous examples from art history of artists being distinguished for their subject matter or materials, labeling is clearly not a thing that can be judged as entirely good or bad.

The language of his art utilizes these two materials to relate a variety of stories, including some from the artist’s personal life as well as sociopolitical accounts from the turbulent history of both Korea and the wider world. The plots of these stories are either highly sensitive to literature or they overflow with a sensitivity that emerges from a cultivation of literature. They are soaked, lingering affection and sympathy made all the more visible through exaggeration, reduction and other forms of expression, in the quiet visual language found deep inside these expressions.

Son Bong-chae began using bicycles as his subject matter and as tools for artistic expression in the mid-nineties. He selected bicycles as his medium for their popularity and familiarity, as well as for their utility and extreme anonymity; however, he also based his decision on a desire to praise these most basic means of transportation as being one of the most practically useful inventions for bipedal animals. We all retain good and bad (but mainly meaningless and vague) memories of bicycles, but in only a few cases are they remembered as something really special. To those of us living in the city, where they have been replaced with more complex and active vehicles, bicycles are now just a distant memory.

Of the bicycles he creates as art, few can function as would normally be intended. They may appear as bicycles from a distance, but a closer examination reveals that most are in fact dysfunctional; some have to be pedaled backwards, others by an odd number of feet. By altering his bicycles to move backwards, the artist reverses the forward-going fate of bicycles. This ‘reversal’ demands that spectators create sociological as well as humorous interpretations of his art. They are unexpected questions that demand from viewers sometimes painful, sometimes pleasurable answers. The spectators end up in accord with the artist’s thoughts and actions that, through his art of retrogression, express the sorrows of the underprivileged crushed under the weight of their lives who are forced to swim against the current of their times.

Son Bong-chae controls the scale and use of his bicycles by crafting the molds for each one himself. His first formal bicycle exhibition was in 1997 at the 2nd Gwangju Biennale. The installation consisted of 207 bicycles of different sizes and functions filling the entire exhibition hall; their operation resulted in a mechanical groan that echoed throughout the space as if it were the voices of the underprivileged being oppressed by power. Later, he created a collective bicycle that requires collaborative pedaling and participated in a variety of exhibitions. Such ‘collective narrative’ pieces were accompanied by light installations throwing a jumble of shadows on a wall that appeared reminiscent of the roar of civilization and the spectacular violence caused by this noise.

These installations are meaningful not simply for their social aspects or because they constitute a beneficial medium to convey the petit-bourgeois lifestyle. The chorus of dozens of human-like bicycles large and small is at times plaintive, but at other moments this sadness comes across as beautiful, transforming the chorus into a declamation.

Son Bong-chae’s other material of choice is panel paintings, flat images superimposed in such a way that, together, the resulting image appears three-dimensional, as in a hologram. Initially they were piles of drawings on glass sheets that created three-dimensional landscapes and portraits, but the glass sheets turned out to be too fragile and difficult to handle. He first replaced the glass with acrylic, then later with polycarbonate, and he has been using it ever since. Son’s panel paintings deal with a diversity of subjects. Sceneries that include pine trees and bamboo, figures, historical places from within Korea and abroad, sites where social and political events and incidents took place; this is his main subject matter.

His father once related to him the story of a pine grove where during the Korean War 124 police officers were ruthlessly massacred by North Korean soldiers. The tale was followed by a visit to the described forest. Today, the pines surround an ordinary village in Gokseong, Jeollanam-do, which is also his father’s hometown. At one point in history, however, it was a place stained with blood. Son Bong-chae went on to paint that pine grove layer by layer on panel after panel and, as if expressing the thickness of its history, he overlapped the paintings to create a three-dimensional effect. This was the beginning of his superimposed paintings.

In the period that followed, his work took him to a range of locations, including the Alhambra in Spain; Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s ‘nose mound’, where the noses of 22,184 Koreans are said to have been buried; the financial center of Shanghai, home to the largest number of Five Star Red Flags on display; the red-light district of Venice; the site of the Nanking Massacre; the spot at which an elderly woman hung herself to escape abuse from her daughter-in-law; the scene of the Daegu subway fire; the center of the Gwangju Democratization Movement; it was as if his aim were to capture history itself.

One of the most notable characteristics of his work is the way he renders trees as if they were sketches of the bleakest sites of history. His panel paintings, mainly depicting Korea’s conventionally symbolic pines and bamboos, stand in stark contrast to the majority of works that portray scenery. This is owing to a stark sense of reality inherent in Son’s treatment of trees as subject matter, along with the way in which superimposing the images to cause that reality to appear three-dimensional emphasizes the strict linguistic meaning that surpasses the subject matter. His trees are portrayed as if they are on the brink of providing testimony and casting accusations regarding the events that took place in their surroundings; as if the stream of ominous languages that flows obliquely out of the pine and bamboo forests is presenting the fact that these places remain mired in historical memories of pain and bitterness.

The sceneries that he chooses to paint are derived from existing views and the backgrounds and figures that appear in his works therefore include a strong sense of reality. Since Son’s works consist of three-dimensional images completed by superposing numerous polycarbonate layers, each of these polycarbonate images appears to be a cross-section of the whole. In addition, LED panels or other lighting devices are attached behind each completed piece; there is a marked difference between viewing the pieces with and without the lighting. To reiterate, it is a point of interest that even historical realities can be dramatized through lighting and other methods.

While Son Bong-chae’s readings of history through realities may at times have a documentary feel to them, they convey a message that transcends those realities through methodical originality along with additional factors such as the supplementary effects created by the use of sound, lighting and shadows. It is my personal belief that such subtle metaphors provide ample evidence to counter the error of pigeonholing Son Bong-chae as simply one more realist artist.

Lee Yongwoo (Art Critic, President, Gwangju Biennale)