Gazing into the Abyss

He who battles monsters must beware,

That he himself does not become a monster,

For if you gaze into the abyss,

The abyss gazes also into you…

- Friedrich Nietzche, from Beyond Good and Evil .

With closed eyes, the outward appearance of individuals varies wildly. As if boasting its global IT reach, Korean society broadcasts with stunning speed diverse forms of information in real-time by means of social networks. Nonetheless, the subjects featured in Chang Hong Ahn’s Forty Nine People's Meditation appear as though time has completely ceased. Their eyes may be closed as if immersed in meditation but from a different perspective they appear to be staring straight at the viewer. Since their souls are fated to wander the present with open, glaring eyes, Chang Hong Ahn perhaps had no choice but to quietly paint shut the eyes of the anonymous occupants of his ID photographs. By pouring over a centimeter of epoxy across a metal frame, Ahn causes his subjects to appear as if they had been submerged for eons. The faces of those who have submerged into this abyss are certain to grow worlds apart from when they initially visited the studio for a portrait.

Identity photographs, by definition, are intended for use in national ID cards, passports or resumes, and their purpose is clearly understood. The individual as a unit of society is expected to use ID photographs to demonstrate their existence on documents for seeking employment or when applying for certain exams, and for the purposes of the photographs they must conform to societal norms to the best of their ability. Moreover, they are standardized manifestations of the desires that those individuals within society yearn to fulfill, and while these pictures may be small in size, they serve as a point of contact at which society and the individual collide. By interjecting at this juncture, Chang Hong Ahn establishes a certain rift. Expanding the photographs and widening the gaps between different interpretations by applying pictorial imagination and methods of expression to these photographs, he has transformed the subject matter to appear as funeral portraits. In particular, the butterfly on the screen creates the impression that its very existence has breached the boundary between life and death. Alas, the wings of this butterfly have been saturated, restricting flight and condemning it to perpetually and aimlessly roam. In this manner, the abyss of Korean society draws nameless individuals into its unfathomable depths while endeavoring to maintain an unruffled surface, appearing as if nothing had occurred. Nevertheless, Chang Hong Ahn gazes into this abyss, unearths what we may wish to leave submerged, and poses a question as to our next move.

This is a theme that he has been continually addressing since his earliest days as an artist in the 1980s. At that time, Korean society was suffering the brunt of the post-Korean War ideological battles between the left and right. In addition, the authority behind the development-focused dictatorship had prioritized economic growth and was credited with the unprecedented economic surge referred to as the ‘Miracle on the Han River.’ This growth came, however, at the cost of a diminished sense of self-reflection and plurality, which had been sacrificed in favor of social control. The art world had not been exempt from the yoke of authoritarianism, and experimental art by young artists had been squelched during the 1970s as the economy was first beginning to take flight--Korean art had sunk far beneath a stratum of Asian philosophy. With the 1980s, populist art touching on social themes and the role of art within society grew ever more prominent. Come the 1990s, the Olympic Games and political democratization led to dynamic, and diverse cultural phenomena. Apace with such social trends, art has also made significant progress. Amidst these developments, Chang Hong Ahn expressed his views by participating in Reality and Utterance, a leading artists’ group representing the populist art movement. However, he soon began to formulate his own voice and refused to conform, something which developed amidst complex and multi-layered circumstances and that has earned him a place in the history of modern art. At a time when forms of public activism centered around ‘collective uniqueness,’ ‘the group’ and ‘the movement,’ the path he chose was a difficult and lonely one. Still, he persists in speaking out against violence committed against the socially disadvantaged; those who vanished under the banner of the modernization and full force development of Korean society, as well as the true face of the power behind it all.

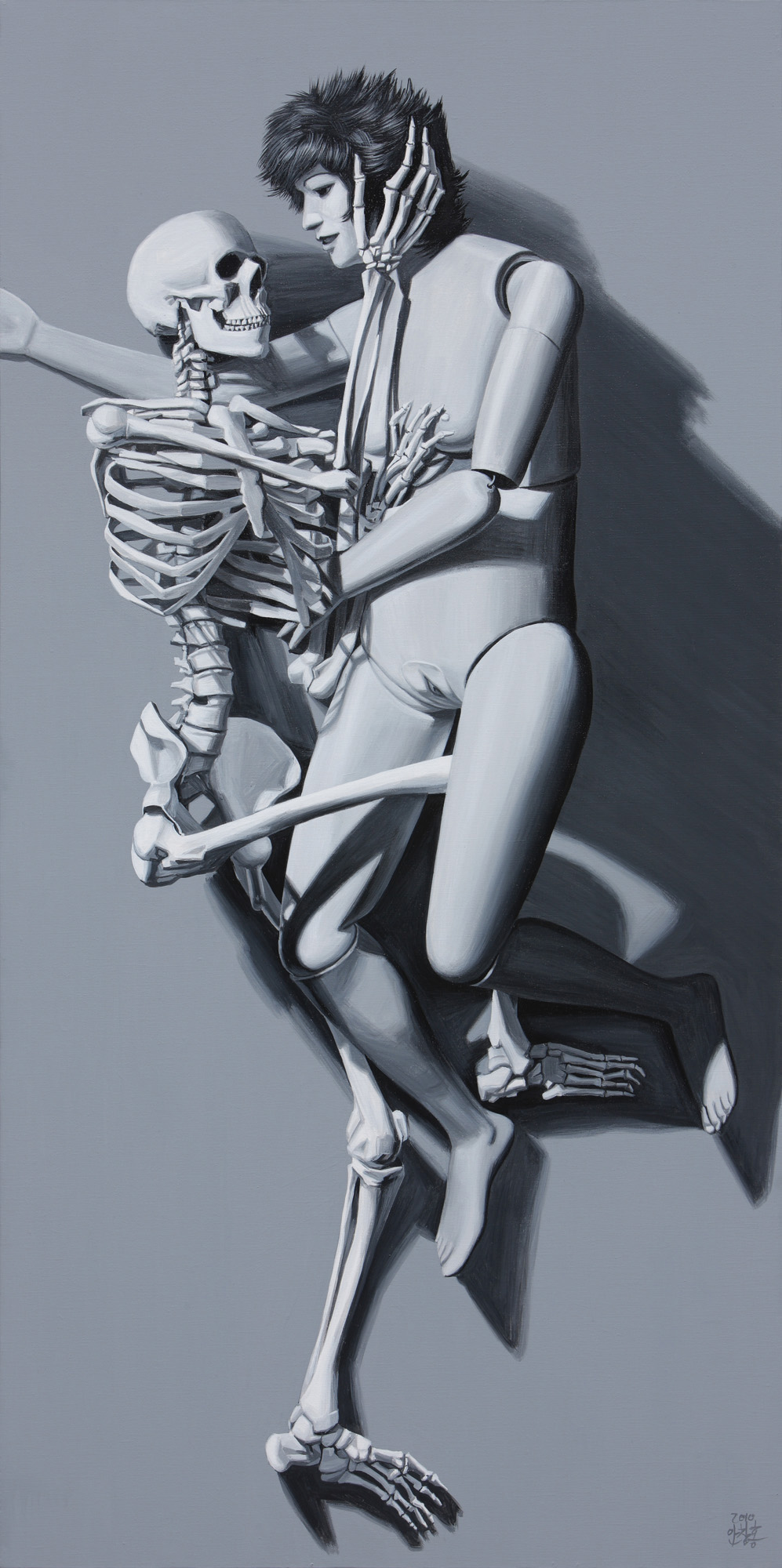

This is not to say that the images he portrays on the screen represent a dry documentation of facts or an over-emotional expose. They are in fact a record of the victims of authority and their souls. Hence, both photography and the body, as vessels and representations of the soul, appear on the screen as effective testaments to the extent and significance of this damage. Subsequently, the physically invisible is visually reproduced, manifested as an extraordinarily powerful and effective image, and invoking a peculiar sensation of witnessing someone else’s nightmares, fantasies, or sacrificial offerings. That scene would resemble the horrid, schizophrenic hallucinations of contemporary society stemming from its violence and failure of communication. They may also be described as tracks left by anti-social cruelty combined with oppressed desires and doubt. Such imagery may share its roots with fantasies stemming from fear of loss and anger in the face of isolation that were experienced by Chang Hong Ahn as a sensitive youth whose childhood was marred by forced separation from his mother.

In this regard, an early work entitled Family Portrait serves as a vital clue to understanding his artistic viewpoint. This piece starts with a black-and-white family photograph, ordinarily a symbol and commemoration of happiness, then gouges out the eyes of the family members and represents them as ghoulish figures. Certainly it is not just Korea where the family is emphasized as a basic unit of society, though it is true that in Korea, where the patriarchal family collective has been given prominence through centuries steeped in Confucianism, the family has long been held as sacred whose values were not to be questioned. In the face of such social constructs, Ahn succeeded in the 1980s in surfacing an aspect of the abyss of Korean society by mutilating the bodies appearing in a family photograph. He had already begun predicting the disintegration of the family in modern society, and the consequent fundamental instability in society, and impoverishment of the mind. An insight made possible not only by the artist’s acute intuition, but also by the fact that he is not an ideologue who quotes theories or circumstances which he does not necessarily agree with, nevertheless asserts them as if they were his own in order to sway those around him. As a consequence, his artistic world may first appear as a hallucinatory shard of a schizophrenic, but one discovers it is in fact stringently grounded in reality and things that physically exist. This is why, when viewing his work, discomfort and repulsion supersede dreamlike sentiments. In essence, the reality that he showcases consists of components that Korean society had long buried deeply, or at least wanted to. Therefore, when such items materialize in front of our very eyes, when they exploit ‘rifts’ to mutate into diverse forms within our psyche and strike the surface of our own personal abyss, we loath to accept them as realities. When faced with his work, we may feel consequent shock, repulsion, and a sense of the bizarre, all coupled with curiosity and guilt that accompany the voyeuristic act of gazing into the forbidden. And yet, we grow even more willing to dismiss such emotions as fantasies or hallucinations, which is merely wishful thinking on our part. There are myriad more horrendous realities intertwined with the mundane and passed unnoticed. This is the case not only in Seoul, but in New York, Tokyo, and Stockholm; anywhere where political authority and individuals can be found. This is also the reason his works have sparked empathy and universality that transcend location and age.

He also traces back in time with Commemorative Photograph - Yellow Butterflies Flutter, another work using acrylic paint and an enlarged original photograph taken in commemoration of the establishment of the State Council of the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea (October 11, 1919). It is one of the most prominent photographs featuring the patriot Dosan Chang Ho Ahn (1878-1938) who overcame all conflicts and confrontations to assume leadership in the independence movement against Japanese colonial rule. However, it is merely a tragic portrait of those who fell to their knees in the face of the power and aggression of the Japanese colonialism that dominated the Korean Peninsula. Bloodstains run down the entire scene with mangled bodies, and the butterflies fluttering about signify victims of power, and the wretched humans vanished with time like butterflies in spring. The artist claimed that when he set about to work, he passed long hours in heartfelt conversation with the figures in the photographs and pondered what might be crossing their minds. Commemorative Photograph - Spring Day Goes was created by Ahn by reshooting, amplifying, and then retouching a photograph of his wife taken during an elementary school spring picnic. He recalled that at the moment he discovered this picture on the dressing table, he became deeply immersed in its symbolism with an enormous royal tomb signifying death and the eventual futility of power; the gloomy ambiance of a faded black and white photograph as if the spirits from a dazzling spring had all been absorbed; and in the expressionless silence of the then-young girls who seemed to predict the vanity of a fleeting life; as well as the contrast and conflict among these remarkable symbols. For about eight or nine years since, the artist often gazed at the figures in the photograph, speculating upon the kinds of lives they would lead?indeed, they did live?and listening to their stories. He then realized that their lives, generalized in the delicate network of the contemporary history of Korea as ‘the people’ without being afforded individual names, could not invariably be depicted as happy. Thus, this artwork presents the chasms, blood and masses of butterflies.

Such thinking is reflected in Broken Face, in which additional symbolic methods are used to convey a variety of messages. The artist created solemn black and white images in acrylic by cutting and dismantling female faces from photographs, then rearranging them on expansive canvases. His technique of first disassembling and then reassembling entities through the act of mutilating bodies, as in ‘broken faces’ literally, recurs throughout his entire body of work. In doing so, Ahn intends to metaphorically depict certain individuals forcibly transformed against their will under violent circumstances. These allegorical methods present opportunities for a myriad of interpretations, subsequently conveying further messages. The external power imposed upon individuals could be viewed as politics, capital, the mass media, or perhaps even as a hierarchy that naturally occurs in any human relationship.

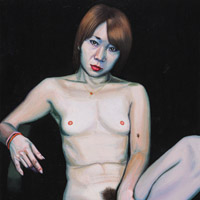

In the Bed Couch series, the realignment of bodies based on somber black and white images is replaced with actual portraits of contemporary individuals. They are common people such as farmers or acquaintances who live among us all. However, each model appears to be the true, proud owner of the body lying on the settee, presenting his own body as the central focus of the picture. The body as a vessel containing the soul is presented as an entity; they also attempt to demonstrate their existence through honest gazes and postures. In retrospect, however, anonymous individuals remain the central characters in his artwork. While his works may record the scars and wounds of wretched souls, the invisible surroundings convey Ahn’s heartwarming humanism and sympathy, in contrast to blood. Consequently, even if the artist gazes into the abyss, he does not lose his way. To this day, he has not ceased dredging up fragments from the abyss and setting them afloat. That is why, tonight, we will find no comfort in sleep.

Kang Soojung (Senior Curator, National Museum of Contemporary Art)

The Success of ‘Uncomfortable’ - Large scale monotonous nude paintings of Ahn, Chang Hong

Ahn, Chang Hong recently held two major solo exhibitions in Seoul and Busan. The "Portraits of the Times" exhibition in the Busan Museum of Modern Art presented 170 of his vast medium works including previously unseen works, 6 black-and-white la,rge scale nude portraiture series, photo collage works, portraitures and self-portraitures . These are Forty Nine People's Meditation, Cyborg's Tear, Cyborg, Museum of Natural History, Hair Style Collection, Broken Face, Family Photos and Face, just to name a few. This exhibition was the third homage from Busan paying tribute to a Busan-born artist, following the previous Bongsaeng Culture Award (2000) and Buil Culture Award (2001). Also, this exhibition was significant in the sense that Busan Museum of Art placed Ahn , Chang Hong directly in the centre of the main contemporary art scene, who had previously trotted a non-academic stance.

The exhibition held in Seoul, Savina Museum, "Black & White Mirror - Some Ghosts or Apparitions," showed 14 of his black-and-white paintings including four of his works, two of his recent works, along with nude paintings and drawings. Ahn's large scale paintings were seen as stage backdrops with the figures as protagonists when placed in the recently remodelled Savina Museum, further elevating the emotional aura of the works, even endowing certain meditational effects.

His series depicts Ahn's acquaintances, and were produced last year and this year. These large paintings cast strong yet enchanting resonances, and even arouse some sort of uncanny uneasiness, tensions, feelings of inconvenience or unpleasantness that deserve further scrutiny. I want to dwell on what those disruptions, inconveniences or tensions signify in these works.

Ahn is already in the spotlight of Korea's art scene with his 'confident/daring voice toward the society', 'gaining influence and independence as an artist', and as an 'energetic and prolific artist.' The major motifs in his works are stream of conscious, flexibility, instinct and concentration alongside self-indulgence, pursuit of aesthetic pleasure, decadence and provocation. Ahn is highly sensitive and alert to human solitude and emotional residue and wounds.

This is not irrelevant to the fact that he often portrays so-called peripheral classes in human society: prostitutes, womanizers, homosexuals, transvestites, women of leisure, political parasites, gangsters, etc. His works often reveal his cynicism toward the snobbish pursuit of political power, public norms or hypocritical attitudes. He adopted a somewhat twisted provocation and destructive ambient to efficiently portray these ideas.

How, then, can we interpret his monotonous, large scale nude paintings? When I first saw his series in Busan Museum of Art, it took me some time to wholly digest the uneasiness. In other words, I had to ponder his works for a certain amount of time until I realized that this uneasiness is the important key to understanding his works. Also, his adoption of 'non-style' as his style, and the implied so-called ' spirit of the times,' as portrayed in the subjective perspective were what made his works interesting. His works connote some sort of uneasiness, a sharp gaze toward the external world with sincerity.

His series adopted nude genre paintings as for subjects matter and style. However, he completely violates and twists the assumed genre code of nude paintings in the figures' poses, interiors, props and ambience. The background of the paintings looks like painter's atelier or at least some abandoned factory. The nude is lying on a bed couch which is in a dirty and messy interior.

The relationship between the props, bed couch, and the human body is somewhat abrupt, whimsical, and 'inappropriate.' The whole scene endorses the cliche of pornography in itself. In other words, the whole scene in the painting seems a bit 'uncomfortable.' Furthermore, when we look at the whole mise-en-scene, his interior is devoid of any ornament and is a highly sachlighkeit situation. The interior only creates a somewhat awkward situation, as if conveying a 'here and now' sentiment. The naked figures are all his acquaintances, posing nude only after much persuasion by the painter, i.e. with the 'trick' of painters.

The figures are both males and females, and most of them are nude. Their naked bodies retain a certain sense of sachlichkeit (more daring and materialistic than Manet's Olympia). Also, they are like some structures portrayed in a serene and solemn tone. However, their direct gaze at the viewer exposes a certain sense of immersion, concentration, voluntary devotion and confidence even though they are naked, and it goes beyond simple pornographic or sensuous sentiments. These sentiments are sudden, impromptu, and (in a certain sense) silly, and the whole scene and produced situations are buried in serenity and solemnity. In this sense, Ahn's nude paintings are very different from any other nude paintings with their extremity, uneasiness, heterogeneity and, of course, with the sublime nature.

Ahn's works often connote a somewhat twisted humour, cynicism and his interest in politics. He portrayed the 80s and 90s with his unique perspective in a somewhat gloomy, burlesque decadence ambience; while his twists on reality endow daring provocations to his works. Ahn's monotone nude paintings deviate from the typical nude genre paintings with the scale of the works and sachlichkeit-reality, and these differences instantly intrigue viewers.

Ahn may have evolved from his trade-mark of dubious sentimentality and romanticism based on self-indulgence and cynicism; however, his major character of subtle and faint eroticism and decadent-like ambience are still there for all to see. In the beginning of this review, I mentioned his exhibition was a bit uneasy and uncomfortable; however, such uneasiness is the best achievement of his monotone nude paintings, and the true essence of his art world. His works still retain his consciousness toward Korea’s social political aspects, and his comments go even deeper with serious tones. I later realized that his uncanny, abrupt, large scale nude paintings are the metaphor to Korea's current political and social situations.

Ahn's aestheticism of provocation and political consciousness are still apparent, but he continues experimenting with the sheer scale and dimension of his works. I am confident that his future works would be the heraldry of a new era and advent of vernacular modernism/ avant-garde.

Seong, Wan Gyeong (Art Critic)