Sohee CHO, Savina Museum of Contemporary Art

Birth

1971, Seoul

Genre

Installation, Media, Performance

Homepage

Nine Ladders by CHO So-Hee

Lee Sang Yoon_ Art History

1. Reconciliation with the “old house”

When I look at the way contemporary artists face space, it reminds me of what Santiago says in Hemingway’s novel The Old Man and the Sea: “a man can be destroyed but not defeated.” We can see such determination in several works of “Old House Rehabilitation Project”: it is clear that this “place” is not merely a neutral “space”. Even CHO So-Hee, the artist, confesses her desire to this place. As to the conclusion of it, briefly, however, she eventually gives up fighting the place. Instead, she becomes free from her old conflict to distinguish between the “destroyed” and the “defeated.” It seems more plausible to say that rather than taking over this recalcitrant place, the artist gives a fresh attempt to reconcile with it by turning the old house into a piece of art.

11th of 62-10, Sungbuk-dong: the “Old House Rehabilitation Project” is one typical model of the ‘site specificity’. Director of Space CAN, who planned this project, also explained that “the purpose of the project is to show the process of building another house by analyzing old structure, and its traces and vestiges built by layers on top of each other.” This place is not a sterilized white-cube environment: rather, it is a place teeming with eighty years of the local history and traces of people’s life there, and it becomes an artwork itself. Therefore, it is of crucial importance how well the artwork could meld into the place. It is certain that this issue is a more challenging task than conquering the old house. Cobwebs, the mold, the shaky sliding door, the tiny courtyard with a water basin in the corner – how hard it is to melt art into this place, already full of its own history, time, and narrative! CHO So-Hee’s perspective was different, however. The artist did not manage to dominate nor alter the place by forceful manipulation. On the contrary, she minimized her work so as to facilitate its absorption into the environment. The “oldness” of the Old House, in other words, the “accumulation of daily life” and the “memories” formed by it were thus the actual work of the artist, and in fact a theme that the artist has continued to show via her career until now.

2. I am “what I am”

“I consider the image of existence as floating freely between the two states of lightness and weightiness. It is always in an interrogative and incomplete state. But I am not saying that it is disparate, not belonging to either side. Rather, it is an inclusive condition that embraces the both sides, a “middle state” in which it is impossible to distinguish between the two sides.” (From the artist’s notebook)

From her 2002 exhibition

While many contemporary artists pursue site specificity, at the end they tend to turn place into background. However, CHO So-Hee starts from a different venue to choose the place itself as an art object. It is only possible because the artist, not to estrange the space and works as others, completely identify and homogenize with them. Like the layers of time in the old house, the place and her works in it show the artist’s life, that is, the proclamation “what I am” of CHO So-Hee. She has been commuting to her studio every morning in order to work the pieces that require ceaselessly, daily work. The pieces done by her daily activities such as typing or knitting have been continued even after the closes of each exhibition. In that sense, the Old House Project shares a common denominator, the condensation of daily life, with the artist’s previous works. The artist’s works are not what completes themselves merely by following a pre-planned, fixed figure. Rather, these works are themselves embodying “What I am” of the artist. Apart from the artistic method, the mediums of the works also have life. The everyday objects such as toilet paper, wrapping paper, thread, and candles are neither expensive nor rare – they illustrate fragility and finiteness of life.

3. The Beauty of Finiteness, and Freedom

The appearance of life revealed through such materials is not spectacular, narrative, nor overwhelming. The old tradition of the artists to pursue three-dimensional illusion, preferably the most splendid one, on two-dimensional surface, runs into an undeniable doubt on the “life of reality.” The more spectacular and grandiose an illusion is, its grandness in face of the vulnerable reality becomes ever smaller. The materials that CHO So-Hee has chosen, such as fabric pieces, paper, and thread, usually have its physical limits coming from its thin, weak, and breakable disposition. They are also torn, dispersed, and polluted even to tiny stimuli. They are our life - breakable and worn out. They also recall “memento mori” on the limitedness of mortal existences. Despite all these, the sentiments underlying her works never exhibit void or futility. On the contrary, the finiteness of being adds more meaning to these. Tenuous and worthless it might seem, however, these qualities add more values to the being.

Another reason why CHO So-Hee’s works do not lean to pessimism is its poetic beauty and liberty. The materials she uses, despite of its physical volume and texture, are to some degree immaterial. The ladder unable to climb up, and the shoes and dresses made of fragile gauze are immaterial. The shiny white threads of the ladder look like thin rays of sunlight that spill into the old house. The shadows of the threads that fall on the walls and floors become drawings generated by utter happenstance. CHO So-Hee’s works - mutable, non-stable, and non-typical float between the immaterial and the material. The freedom and amusement derived from the immaterial elements turn the fragility and finiteness of materiality into wonder and lyric. The artist seems to instinctively feel such joy. The fact that CHO So-Hee is not paranoid or obsessive about figure and image also implies that she is fully enjoying herself on the border between the material and the immaterial. In other words, she is free from the pressure and exhaustion of defining and accomplishing something.

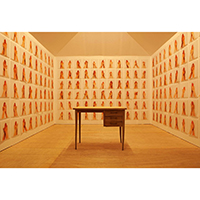

4. Nine Ladders

This exhibition,

“Examining the various pores and veins of the nets I knit helps me better perceive existence. It is like appreciating the cool and tickling texture of the stream that flows through the toes under water. It is not a mind-boggling thought about the river, but the tactile pleasure of the water and its flows.” (From the artist’s notebook).

Lee Sang Yoon (Visiting Professor of Art History at Seoul National University)

A Tree Across the Road_Listvyanka, A lonely tree

A Tree Across the Road

Listvyanka, A lonely tree

This world is filled with things that can be defined by a dictionary, and yet the language used in the dictionary alone cannot even assess the scale of day and night. In a dictionary, a tree for instance is defined as a noun; a perennial plant whose body consists of a trunk and branches; which produces timber used to build houses or to craft furniture and dishes. The detailed aspects of a tree are so numerous that each aspect is again described separately in the dictionary.

One of the idioms that aptly harbors the time-honored wisdom and aesthetics of East Asia is Suihan Sanyou (歲寒三友), referring to “the three friends of winter”: pine, bamboo, and plum trees. This expression and the significance of the three trees embody a system of symbolism that the people of East Asia “have endured” over time. The implication of these trees, which deeply permeate into the philosophy of life, connotes qualities such as fidelity, integrity, seclusion, unworldliness, friendship, faith, humility, and morality. The system of meanings embodied by the trees correspond with the ideals pursued by the people of East Asia, where such values were held as the greatest virtues of life.

Here is a poem by a certain poet. It is one of the poems included in an anthology of the poet Chae Ho-gi, titled Water Lilies. As the title of the anthology and the underlying thematic keyword, “water lilies” are categorized as a plant in the order Nymphaeales, family Nymphaeaceae, and genus Nymphaea. For the poet, however, water lilies are an aesthetic object, which he depicts using poetic language. Go Jong-seok, a Korean literary critic, described “water lilies” in Chae Ho-gi’s poem as the summer heat weltering beyond the waves of sensuality. Behold!

On that summer day, when I first saw you;

I should have known, before I fell in love with you

That I was standing on the earth,

Whereas you, the water lily, were standing on the water.

From Water Lilies by Chae Ho-gi

I cannot see your body. But to magnify the minute details of your body shows a swaying floral cloth woven with petal thread.

From Air by Chae Ho-gi

In Water Lilies, since “I” was standing on the earth, whereas “you” were standing on the water, love between the two appears impossible. As far as “I” can see from the land, is “your” body out of sight and merely swaying above the water? The sense of longing towards this swaying image is expressed in poetry as the “floral cloth woven by petal thread.” Through poetic imagination, however, the poet opens the door to a world where love between the two is made possible. When the poet remarks that “the edges of the water lily petals lure you in / surrounding the water lilies, you summon their white petals / Ah! Such delightful suppleness!” It is without doubt that “you” and “I” have jumped in with our naked bodies, swaying alongside floral cloth woven by petal thread.

Regard Listvyanka by Cho Sohee. This short piece of video art runs only 11 minutes and 16 seconds, but required around five or six hours of walking to produce. There are reasons why the hours she spent to encounter the tree that she had seen through the window of a car, and the moments she spent as if playing a game of cat’s cradle with the tree should not be interpreted simply as the story between a tree and an artist. The tree was a conifer standing on the grassland near Lake Baikal, but it also was a “spirit tree of the skies above.” Cho Sohee shared with the spirit tree “the summer heat weltering beyond the waves of sensuality” as in Chae Ho-gi’s expression. “I” stood on the grassland, whereas “you” greeted “me” with your roots planted into the earth. The artist had travelled to this place and then returned, whereas the tree remains firmly grounded on the edges of Lake Baikal, left to sway alone. In order to express her longing towards the swaying of this tree, she wove a net in red thread around the tree as if it were floral cloth woven by petal thread.

As such, Cho Sohee’s world is no different from the way the world of trees is understood or the way water lilies are painted. However, I believe that the elements present in her artistic world, such as thread, skeins of thread, paper, skeins of paper, candles, candle holders, tables, chairs, cat’s cradle, and thread nets as well as the series of performance-like actions such as walking, the performance of walking, cat’s cradling, the performance of cat’s cradling, typing, and the performance of typing are constituted in a structure that can only collapse with ease from the failure to find the language of another world that may continue on from such elements. Cho Sohee seems to have invented a language consisting of “Cho Sohee’s lexicon of aesthetics,” which she herself has woven over the long history of her artistry. This may be likened to an epic poem comprised of poetic words and phrases. In other words, the poem does not consist of easily-read written words, and instead often transforms into the language of imagery or takes on a form of pantomime to enhance the ease of comprehension. Therefore, we as the audience might perhaps have to set aside the symbolic system of written language that we have been using thus far. This is because the tree is a specific object that we have referred to as a tree, and also simultaneously the symbol of a tree, whereas the mesh net often shown in her work is a specific object referred to as a net, while also the symbol of a net. In order to enter Cho Sohee’s world, we have to see not only the tree but also the world that the tree reflects; so as to see the net, we have to see the window of the world which is reflected by the net.

Indeed, this writing is a description of the artistic world of Cho, who was compelled to euphorically confess, “I cannot see your body. But to magnify the minute details of your body shows a swaying floral cloth woven with petal thread.” Furthermore, this paper is nothing but the record of a monologue of self-directed questions and answers. This means that this conversational record is composed in a structure in which each part is a question and an answer in itself, while the whole may also be a question and an answer. Since there can be no answer that erases the question and no question that is completed by an answer, the aesthetic performance that is deeply driven by Cho’s way of thinking lies somewhere between the question and answer. Just like the swinging pendulum of a clock, she oscillates between answers that are impossible to exist and questions that are impossible to complete. So it may be safe to say that, based on the act of net-knitting through countless knots, her works have not been completed yet, at least, not yet.

A thought on walking

Suppose that a man is walking only for the sake of walking, and that his walking has an unfathomable philosophical depth. If so, what is the philosophical depth of his act of walking and the weight of his steps? Is it possible that walking, the weight of the steps taken, and the act’s philosophical depth mutually share a semantic structure to ultimately form a happy triangle?

A long walk is no different from walking without moving. The immobility here is not in a physical sense, but instead refers to the composure of his mind. A walker chooses his residence not in space, but in time. The act of walking is to live in one’s body, whether for a short while or a long period of time. Walking in the woods, on a road, or on a trail with no other purpose than to follow the path does not exempt one from the duties of the disordered world, but it allows him to collect his breath and sharpen the senses of his entire body. This is because taking a detour to fully focus the self into one place also constitutes the meaning of walking. The road enlightens us about the importance of the fundamental through the actual experience of walking; no, through the ruthless hardship of the act. Walking allows us to escape from our repetitive daily routines so that we can open up our inner paths, far away from our day-to-day life. The act of walking alone can complete a philosophy.

It is said that walking is the antipode of home. In other words, walking is the opposite of enjoying a specific place of residence. This is perhaps because every step that a man happens to take will transform him into a wanderer, a drifter beyond the road. It may also turn him uncontrollable and unfathomable, a man with no home or abode, or a bygone traveler who has already disappeared into the distance. To him, this world may only be a place to rest his head at night. Being here or there may only mean to exist at a certain point of a line, which stretches like a straight road at times, or winds like a mountain trail at others. What does the act of walking signify to you?

An abundance of thought starts with walking. As one walks, he comes to realize that there is no such thing as a thought too heavy to shake off. Sometimes, I do not limit myself to writing only with my hand. My feet always play some part as well. I traverse the plains and walk across the paper. Climb up hills, and you would be surprised to discover the musculature of the path. The opposite can also be true, as shown in the poetry of Matsuo Bashō:

I found that the year had suddenly drawn to its close. As the sky of the new year filled with the haze of spring, I thought of going beyond the Shirakawa Barrier... I mended my underpants, re-corded my rain hat, and took three bits of moxa cautery. I could not put from my mind how lovely the moon must be at Matsushima. I disposed of my property.

An excerpt from a poem by Japanese haiku master Bashō

Bashō’s poem demonstrates the refreshing beauty of lightness. There are several paths around Lake Baikal, where Cho walked. At first, there is just one road, but it forks in different directions into two and three roads, and as they stretch beyond the field, they incorporate into one again at some point. The people there describe the road with the word “wound.” The road’s name literally means “wounded road.” However, if someone starts making another path beside it, the road’s name changes into a “road of healing.” It would appear that walking carries the dual meaning of wounding and healing at the same time. What could we ponder upon on the road that she walked?

In Theory of Walking (La Théorie de la demarche), Balzac wrote that it is extraordinary that no one has ever raised such questions as why and how humanity has continued to walk since its first step; whether it has actually walked; if there is a better way to walk; and what humanity can achieve through walking. He viewed all questions on philosophical, psychological, and political systems as being connected to the act of walking. However, it would be difficult to understand an artist’s walk in relation with the above questions. Balzac’s remark is almost excessively passionate, rather than being literary. Instead, Cho’s walking reminds me of Henry David Thoreau’s essay “Walking.”

He once said, “When I would recreate myself, I seek the darkest woods the thickest and most interminable and, to the citizen, most dismal swamp. I enter a swamp as a sacred place—a sanctum sanctorum. There is the strength, the marrow, of Nature.” Do you understand? Thoreau’s observation is in line with that of Laozi (老子). In Tao Te Ching (道德经), the ancient Chinese philosopher wrote: “All things alike go through their processes of activity, and (then) we see them return (to their original state). When things (in the vegetable world) have displayed their luxuriant growth, we see each of them return to its root.” What then is the meaning of Cho’s walking in search of the tree near Lake Baikal?

In the primeval forests of northern Mongolia stand trees referred to as spirit trees. Distinct from other vegetation, they grow straight and tall as if seeking to pierce the sky, but appear thin with not many branches. Some of these trees, however, grow particularly luxuriant branches, whose leaves are tangled to form a round shape, on a certain branch. This growth sometimes manifests on top of the tree, in the middle, or near the roots. In the first case, the tree is referred to as a spirit tree of the skies above; in the second, a spirit tree of this world; in the third, a spirit tree of the afterlife. These are collectively referred to as the “three worlds,” from the perspective that the world is divided into three realms. The upper world, also known as paradise, is a place of purity, innocence, and absence of sorrow, as the home of good deities such as guardian gods—these good gods protect humans of the middle world from suffering and incessantly fight against evil gods. The middle world is the world of human beings. The lower world, also known as the Nation of Hell, is a place of death and darkness where gods of disease conspire against humanity. Cho Sohee’s tree resembles a spirit tree of the skies above. Here is the story of this tree.

A boy once planted a dead tree near the lake. He watered the tree every day without fail. Three years passed. One day, the boy struggled his way to the tree with a bucket full of water. Surprisingly, he found that the dead tree had bloomed flowers. Since then, the tree has stood alone, enduring such a long passage of time. I heard that Cho walked toward the tree from dawn. After five hours—no, nearly six hours—she arrived at the tree near Lake Baikal. And she knitted a net on the tree, to reach the middle world and the lower one. No one knows why she used red thread to make the net. We can only assume that it was her attempt to connect all three worlds into one through the world of the net, which sways from the upper world to the middle world, and to the lower world. This is nothing short of the second blooming of the spirit tree of the skies above.

Kim Jong-Gil (Art Critic)